Leonard Read (1898–1983) was the founder and later president of the pro-capitalist Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), publishers of The Freeman.

[Page 1]

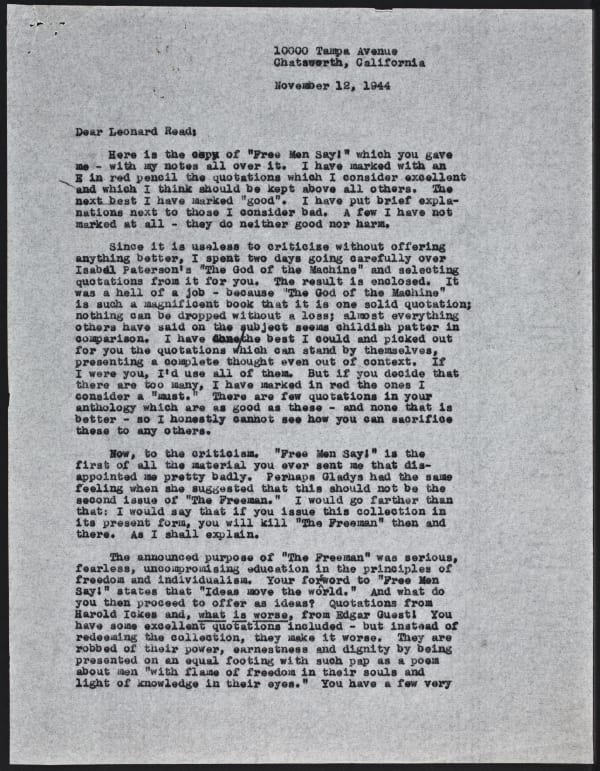

10000 Tampa Avenue

Chatsworth, California

November 12, 1944

Dear Leonard Read:

Here is the copy of “Free Men Say!” which you gave me—with my notes all over it. I have marked with an E in red pencil the quotations which I consider excellent and which I think should be kept above all others. The next best I have marked “good”. I have put brief explanations next to those I consider bad. A few I have not marked at all—they do neither good nor harm.

Since it is useless to criticize without offering anything better, I spent two days going carefully over Isabel Paterson’s “The God of the Machine” and selecting quotations from it for you. The result is enclosed. It was a hell of a job—because “The God of the Machine” is such a magnificent book that it is one solid quotation; nothing can be dropped without a loss; almost everything others have said on the subject seems childish patter in comparison. I have done the best I could and picked out for you the quotations which can stand by themselves, presenting a complete thought even out of context. If I were you, I’d use all of them. But if you decide that there are too many, I have marked in red the ones I consider a “must.” There are few quotations in your anthology which are as good as these—and none that is better—so I honestly cannot see how you can sacrifice these to any others.

Now, to the criticism. “Free Men Say!” is the first of all the material you ever sent me that disappointed me pretty badly. Perhaps Gladys had the same feeling when she suggested that this should not be the second issue of “The Freeman.” I would go farther than that: I would say that if you issue this collection in its present form, you will kill “The Freeman” then and there. As I shall explain.

The announced purpose of “The Freeman” was serious, fearless, uncompromising education in the principles of freedom and individualism. Your foreword to “Free Men Say!” states that “Ideas move the world.” And what do you then proceed to offer as ideas? Quotations from Harold Ickes and, what is worse, from Edgar Guest! You have some excellent quotations included—but instead of redeeming the collection, they make it worse. They are robbed of their power, earnestness and dignity by being presented on an equal footing with such pap as a poem about men “with flame of freedom in their souls and light of knowledge in their eyes.” You have a few very

[Page 2]

2.

bad quotations, contradictory to and downright destructive of your basic principles. But these few are not the worst flaw in the collection. The worst flaw is the preponderance of meaningless generalities which are neither good nor bad, but merely nothing at all. They give the collection an over-all taste of sweetness, timidity, purposelessness and that tone of “benevolent bromides” which is the curse of our conservatives and which has cost the Republican Party three elections. It is precisely the same tone, method, intention and result.

And like all compromises of this nature, the collection not merely does not accomplish its purpose, but accomplishes the exact opposite. The net result in a neutral reader’s mind would be: “Well, if this is the best that can be said for freedom and individualism, it ain’t much!”

Since you are limited in the size of your booklet, your responsibility in the choice of quotations grows in inverse ratio to the number of pages used. Since you have little space, you can afford nothing but the best. Otherwise, you give a dreadful impression of the intellectual poverty of freedom’s cause.

Just ask yourself what earthly purpose can be accomplished by spending money, effort and paper to tell men that “The ground of liberty must be gained by inches”? (What if Jefferson did say it? That was not all he said.) Standing by itself, such a sentence means nothing, says nothing, solves nothing. It is a generality, of no value unless the specific steps or inches are named. Anybody could subscribe to that sentence—and I mean anybody: Ickes, Roosevelt, Stalin or Hitler.

And that is the first test to which you must submit every quotation you choose: could a collectivist subscribe to it legitimately? That is, without contradicting his basic collectivist principles. If he can—your quotation is useless.

The second test is: does the quotation present a complete thought, by itself, out of context—and is that thought of value? If not—the quotation is useless. You have a great many quotes that are obviously parts of a general discussion, but of no particular strength by themselves. A good quotation must be a complete entity. It must be like a headline—sharp, clear, whole.

The third test: can the quotation be misinterpreted? If it can, it is worse than useless, it is dangerous. You have a great many quotations which were probably clarified in context. But by themselves, without amplification,

[Page 3]

3.

they are open to a great many possible interpretations, most of them contradictory to your basic principles. You have many quotations whose meaning and intention are clear to me only because I know you personally and know what you were driving at. That is not proper. A quotation must be clear and unmistakable—by its own terms, through its own words—so that it retains its meaning no matter who said it or who is quoting it. I know that it is hard to find such passages from a long serious book that depends on a long, closely reasoned argument. Still, only such passages can be of any value as quotations. Those that do not meet this requirement had better not be used.

Since the purpose of “The Freeman” is education in principles, you defeat your purpose by publishing anything that has no intellectual value, that does not contribute a forceful, uncompromising, specific THOUGHT on the subject of freedom. Mere ringing generalities, pretty sentences or emotional appeals are worse than useless. They support the general impression that freedom is a vague term without specific content—so that it is quite proper for Roosevelt, Browder and Stalin to pose as champions of freedom. Unless every quotation you use ties freedom specifically to individualism (and contributes some specific thought, reason or proof why this is so) you achieve the opposite of your intention.

You may ask: “But isn’t it proper to stir up a general emotional response to the mere word ‘freedom’, without specific content—and supply the content later?” And I would answer: No. That kind of stirring up is being done for you—by experts. That’s what the New Deal is doing. You would only contribute to the general delusion that so long as we keep on yelling “Freedom” loudly enough, we are preserving it and no exercise of it in reality is necessary, since we do not even have to bother to understand what it means; so that it’s quite all right to have ration cards, social security, forced labor and confiscation of property, so long as everybody shouts that this is a free country.

What is the purpose you wish to achieve by this booklet? To give your readers the best thoughts men have expressed on freedom—the thoughts which they can use as ammunition in arguments on the subject. If your quotations do not achieve this, you have failed. But most of what you have given your readers is not bullets—it’s flowers. Hearts and flowers.

That is why I said that this booklet in its present form would kill the whole venture of “The Freeman.” If I did not know you personally, but had received the first

[Page 4]

4.

issue of “The Freeman”, I would have subscribed with enthusiasm and interest; then, if I had received this collection, I would have said: “Oh well, it’s just another one of those sweet Republican organizations, like the N.A.M.” And I would not have bothered to read the following issues. You know what an ungodly amount of so-called “Conservative” pamphlets is being put out by hundreds of “conservative” organizations and how little good they do. Their fault is precisely the same as that of your collection—vagueness, generality, compromise—a feather duster where a meat-axe is necessary. You cannot afford to be placed in that category. Nor does it fit you as a person. Whatever “The Freeman” puts out must be clear cut, specific and uncompromising. Otherwise, you’ll only help the other side—as all those conservative organizations are doing.

I hope you understand that when I say “you” in all the above criticism, I mean the Pamphleteers, not Leonard Read. I know that this is not your personal fault, since none of your own writing ever had the qualities to which I object here. I realize that this collection is a synthesis, a collective selection and, as such, bears the usual faults of any collective attempt. So I am trying, in this letter, to state the considerations and tests on which I think you can all agree and which can serve as a guiding standard in making your selections.

I must confess one thing: I feel a little indignant that your researchers simply passed up a book like “The God of the Machine”. All you have from it are only two quotations—not the best—picked from the end of the book. Obviously nobody has bothered to go through it. That gave me my usual, dangerous feeling of “what’s the use?” It is a little discouraging to see those who attempt to find valuable thoughts on freedom pass up a treasure mine like this—and devote almost a whole page to Thomas Paine, who was not one of us, as the very quotations you chose demonstrate. This tends to shake my faith in what we were discussing here the other night—the fact that ideas live on their own and that those who need them will find them.

I also think that you should read Roark’s speech from “The Fountainhead”—and not because it’s my book or because I want more quotations from myself. But really there are much, much better quotes in it for your purpose than the ones included in the collection.

Now, a MOST IMPORTANT point: if you entitle your booklet “Free Men Say!” and state in your foreword that these are good ideas expressed by the “lovers of liberty” you simply cannot include Roosevelt, Ickes, Woodrow Wilson,

[Page 5]

5.

Eugene V. Debs and Leon Trotzky (?!?) It is actually indecent. It does what your weaker quotations do—gives specific assistance to the other side—but does it openly, directly and deliberately. It whitewashes, sanctions and supports the enemy. It’s inexcusable. NOW EVERYTHING ELSE I SAID MAY BE OPEN TO DEBATE, BUT THIS POINT IS NOT. If you quote any socialist or New Dealer as a champion of freedom—you have no case or cause left.

I would suggest that you should be very careful in your choice of authors—in view of your title and foreword. I do not know some of them at all. If they are not strictly of our side, if they are doubtful or in-between—throw them out, no matter what they said. No quotation is good enough to offset the harm done by including such names.

Now, a minor suggestion: I would include the titles of the books from which your quotations are taken, along with the author’s name. It would induce your readers to read the complete works, if they liked the quotations—and that would help your purpose. (Provided, of course, that the quotes are from books on our side—another reason why they should be.) Personally, I was very much impressed with the quotations from William Graham Sumner and Max Hirsch, two authors I had not discovered for myself. Would you tell me the titles of the books from which you quoted? I would like to read more of these two.

And would you let me see the final copy of your selections before you print it? If I can help you to avoid dangerous mistakes, I would like to do it. The final decision, of course, is yours. But I would like to express my opinion—for whatever value you may find in it—when it is still not too late.

With my best personal regards,

Exhaustedly yours,

P.S. And I’m the little girl who hates to write letters!

None of the subsequent letters from Read in the Ayn Rand Archives mentions “Free Men Say!”