Gouverneur Morris was a screenwriter at Universal. His credits include many silent films in the early 1920s, e.g., Anybody’s Woman (1930) and East of Java (1935).

[Page 1]

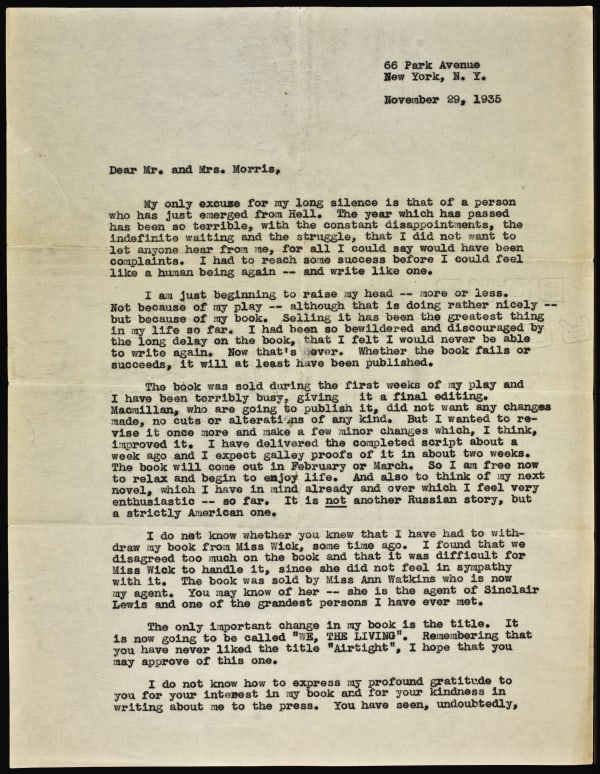

66 Park Avenue

New York, N.Y.

November 29, 1935

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Morris,

My only excuse for my long silence is that of a person who has just emerged from Hell. The year which has passed has been so terrible, with the constant disappointments, the indefinite waiting and the struggle, that I did not want to let anyone hear from me, for all I could say would have been complaints. I had to reach some success before I could feel like a human being again—and write like one.

I am just beginning to raise my head—more or less. Not because of my play—although that is doing rather nicely—but because of my book. Selling it has been the greatest thing in my life so far. I had been so bewildered and discouraged by the long delay on the book, that I felt I would never be able to write again. Now that’s over. Whether the book fails or succeeds, it will at least have been published.

The book was sold during the first weeks of my play and I have been terribly busy, giving it a final editing. Macmillan, who are going to publish it, did not want any changes made, no cuts or alterations of any kind. But I wanted to revise it once more and make a few minor changes which, I think, improved it. I have delivered the completed script about a week ago and I expect galley proofs of it in about two weeks. The book will come out in February or March. So I am free now to relax and begin to enjoy life. And also to think of my next novel, which I have in mind already and over which I feel very enthusiastic—so far. It is not another Russian story, but a strictly American one.

I do not know whether you knew that I have had to withdraw my book from Miss Wick, some time ago. I found that we disagreed too much on the book and that it was difficult for Miss Wick to handle it, since she did not feel in sympathy with it. The book was sold by Miss Ann Watkins who is now my agent. You may know of her—she is the agent of Sinclair Lewis and one of the grandest persons I have ever met.

The only important change in my book is the title. It is now going to be called “WE, THE LIVING”. Remembering that you have never liked the title “Airtight”, I hope that you may approve of this one.

I do not know how to express my profound gratitude to you for your interest in my book and for your kindness in writing about me to the press. You have seen, undoubtedly,

[Page 2]

(2)

the nice mention which O. O. McIntyre gave me in his column on your recommendation.[*] Now that my worst struggle is over, I find many people interested in me, but I shall never forget that you had faith in me at the time when I was just beginning and needed it most.

There is not much that I can tell you about my play. It is doing very well, it seems very popular and successful. But I get no satisfaction whatever out of it, because of the changes which Mr. Woods insisted on making. I find them so inept and in such bad taste that the entire spirit of the play is ruined. I have never considered it as a particularly good play and was fully prepared to allow any changes to improve it. But I do not think that bringing it down to the level of cheap melodrama and destroying its characters, which was the best thing it had, constitutes an improvement. And that is exactly what Mr. Woods has done. I am trying to look at the whole thing philosophically, consider it a necessary sacrifice to make a beginning and forget about it, while I try to write something better.

Since I frankly lacked the courage to write to you sooner, I have never had the chance to ask you what you thought of my novelette “Ideal” which I left with you when I departed from Hollywood. If it is not too late and if you still remember it, I would greatly appreciate your opinion of it. I have rewritten it into a play, which I have finished recently.

I do not know when I shall come back to Hollywood. I would like to stay here a little longer and I do not plan to return, unless the screen rights to my play are sold and I am brought back to work on the adaptation. I love New York. It is a city, and I suppose that I am one of those decadent products of civilization that do not feel at home outside of a big city. With the exception of a few friends, I do not miss Hollywood at all. If and when I have to return, the pleasure of seeing you again will be my chief compensation. That prospect does make me wish to come back some time soon.

If I may be forgiven for my long silence, I would be very grateful for a letter from you. Frank joins me in sending you our regards and very best wishes.

Thanking you again, I am

Sincerely yours,

*McIntyre’s syndicated column appeared first on November 9, 1935, and included this comment about AR: “How proud writers are over a sudden writing success. Gouverneur Morris writes me of his enthusiasm for the showing of Ayn Rand, who at 20 [sic] has a play on Broadway and a book on the presses. A Russian girl, who mastered writing beautiful English in three years. She asked Morris to criticize her first novel. Except mending a split infinitive, he found nothing he did not wish he might have done himself.”

A version of Night of January 16th restoring what Woods cut was not available in print until published by World in 1968. For a 1973 revival, Ayn Rand made what Leonard Peikoff describes as “several dozen relatively small editorial changes,” which were incorporated into all printings since 1985. The play is still being performed, particularly in summer stock and in high schools.