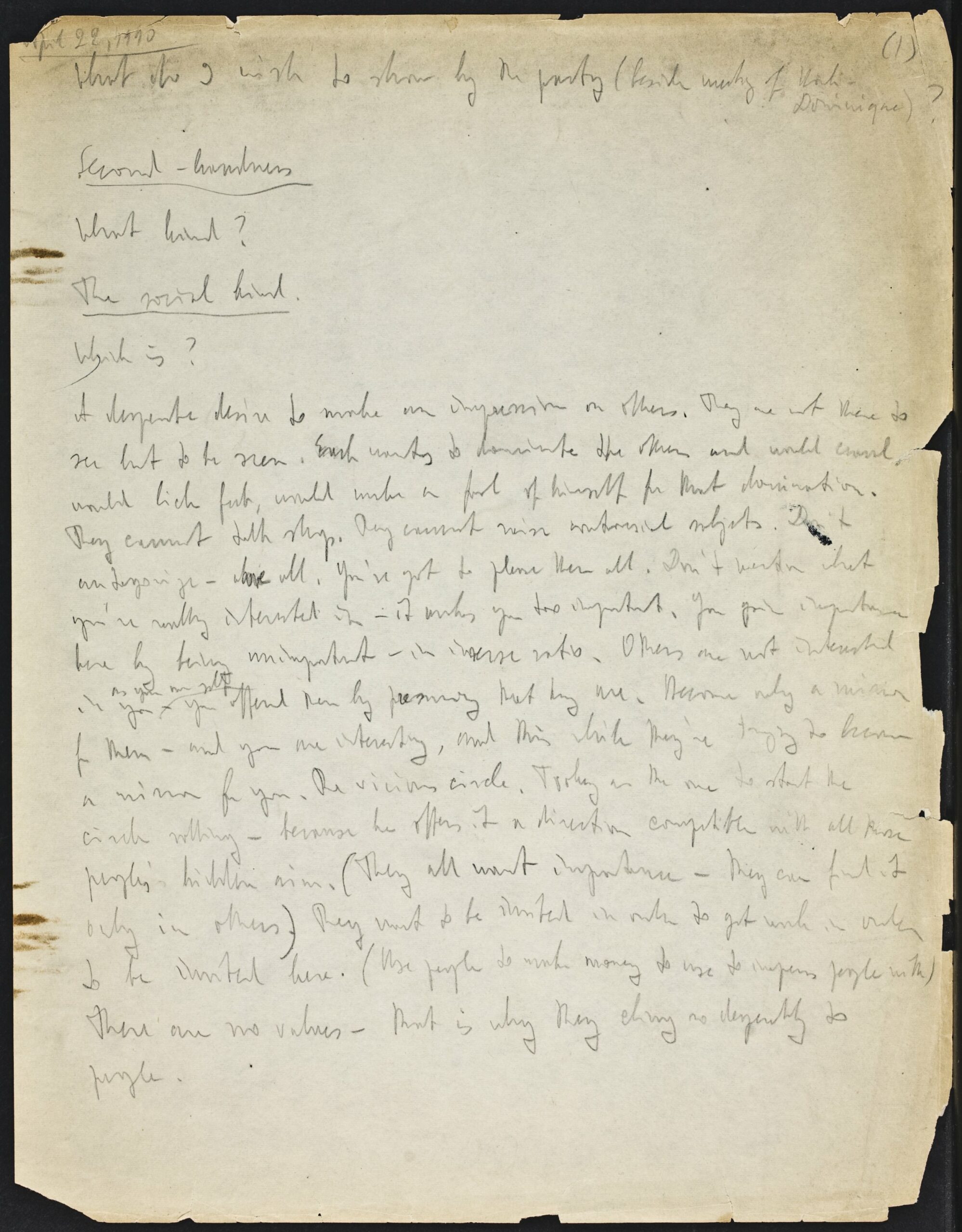

[Page 1]

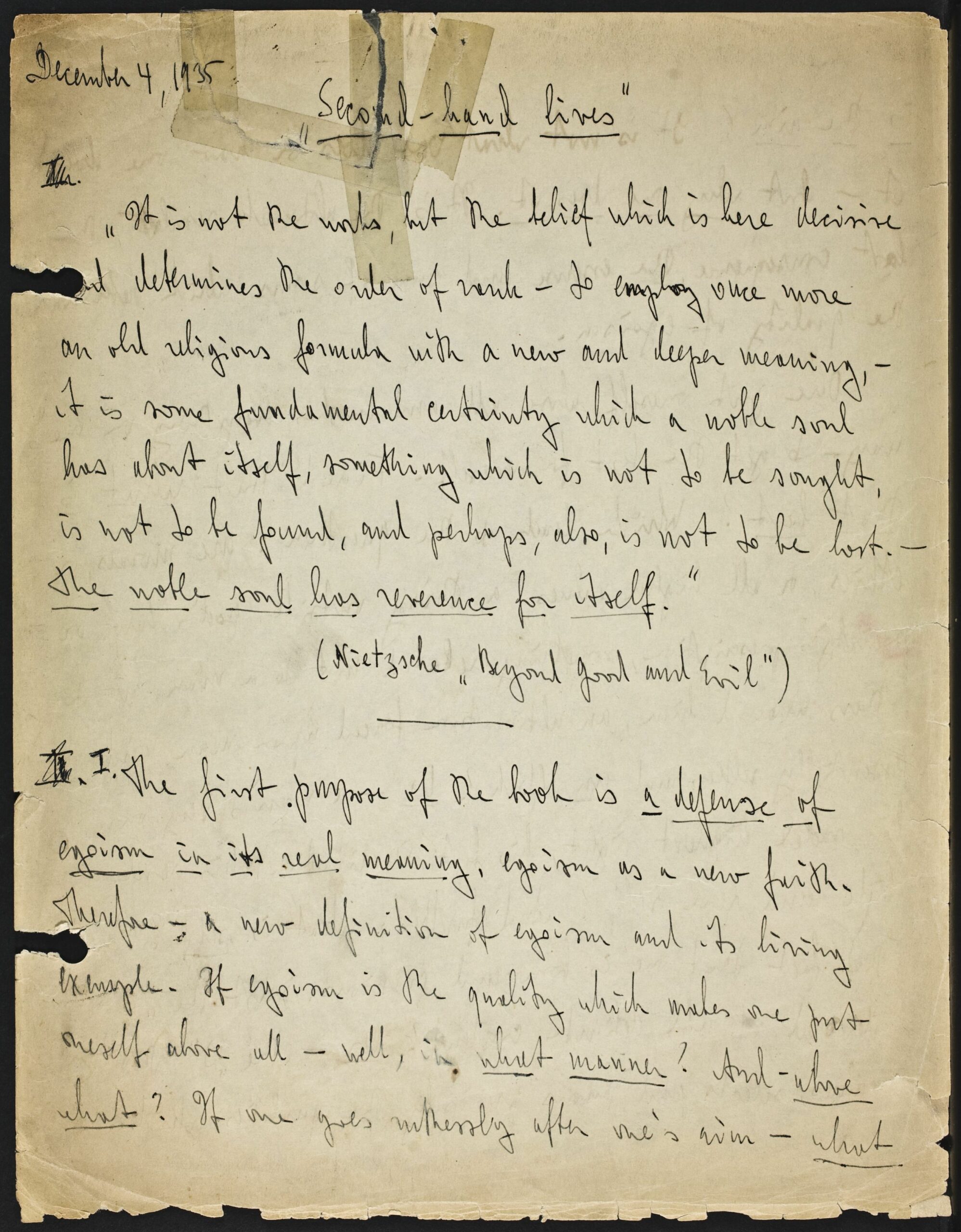

December 4, 1935

“Second–hand lives”

I.

“It is not the works, but the belief which is here decisive [?a]nd determines the order of rank – to employ once more an old religious formula with a new and deeper meaning, – it is some fundamental certainty which a noble soul has about itself, something which is not to be sought, is not to be found, and perhaps, also, is not to be lost. – The noble soul has reverence for itself.”

(Nietzsche “Beyond Good and Evil”)

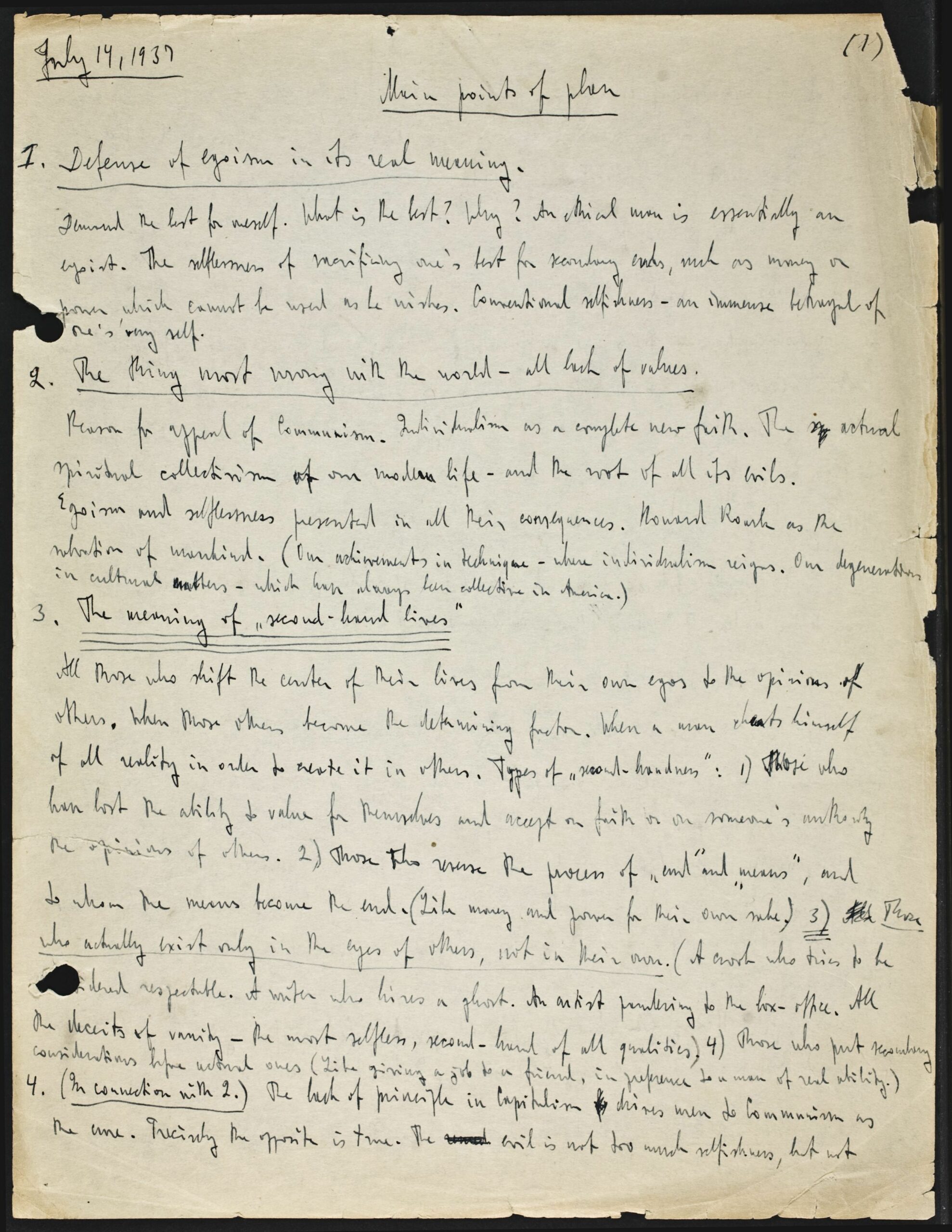

II. I. The first purpose of the book is a defense of egoism in its real meaning, egoism as a new faith. Therefore – a new definition of egoism and its living example. If egoism is the quality which makes one put oneself above all – well, in what manner? And – above what? If one goes ruthlessly after one’s aim – what

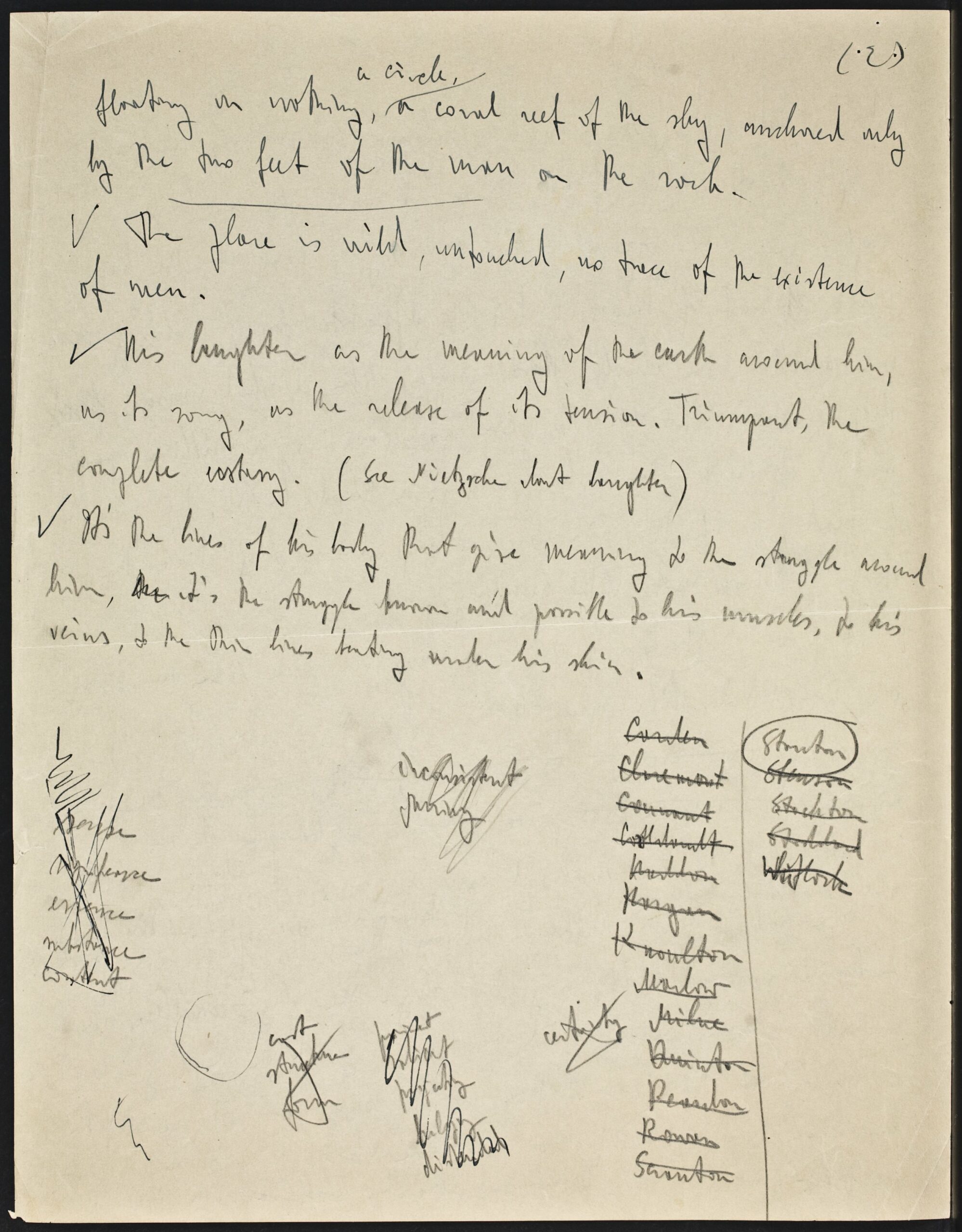

[Page 2]

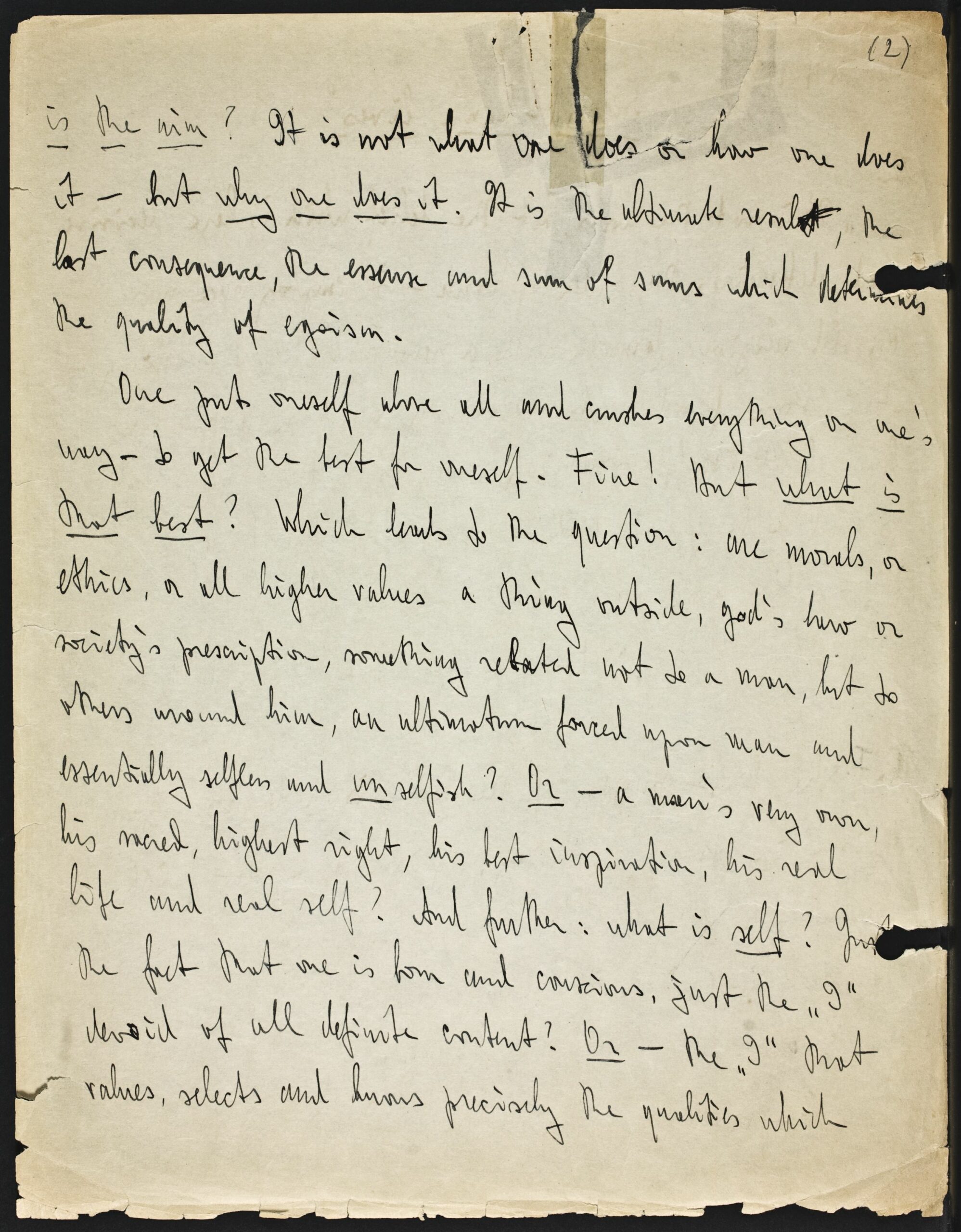

(2)

is the aim? It is not what one does or how one does it – but why one does it. It is the ultimate result, the last consequence, the essence and sum of sums which determines the quality of egoism.

One puts oneself above all and crushes everything on one’s way – to get the best for oneself. Fine! But what is that best? Which leads to the question : are morals, or ethics, or all higher values a thing outside, god’s law or society’s prescription, something related not to a man, but to others around him, an ultimatum forced upon man and essentially selfless and unselfish? Or – a man’s very own, his sacred, highest right, his best inspiration, his real life and real self? And further : what is self? Just the fact that one is born and conscious, just the “I” devoid of all definite content? Or – the “I” that values, selects and knows precisely the qualities which

[Page 3]

(3)

distinguish it from all other “I”’s, which has reverence for itself for certain definite reasons, not merely because “I-am-what-I-am-and-don’t-know-just-what-I-am.” If one’s physical body is a certain definite body with a certain definite shape and features – not just a body, so one’s spirit is a certain definite spirit with definite features and qualities. A spirit without content is an abstraction that does not exist. And if one is proud of one’s body for its beauty, created by certain lines and forms, so one is proud of one’s spirit for its beauty – or that which one considers its beauty. Without that – there can be no pride of spirit. Nor any spirit.

If, then, the higher values of life (such as all ethics, all philosophy, all esthetics, everything in short that results from a sense of valuation in the mental life of man) comes from within, from man’s own spirit – they are a right, a

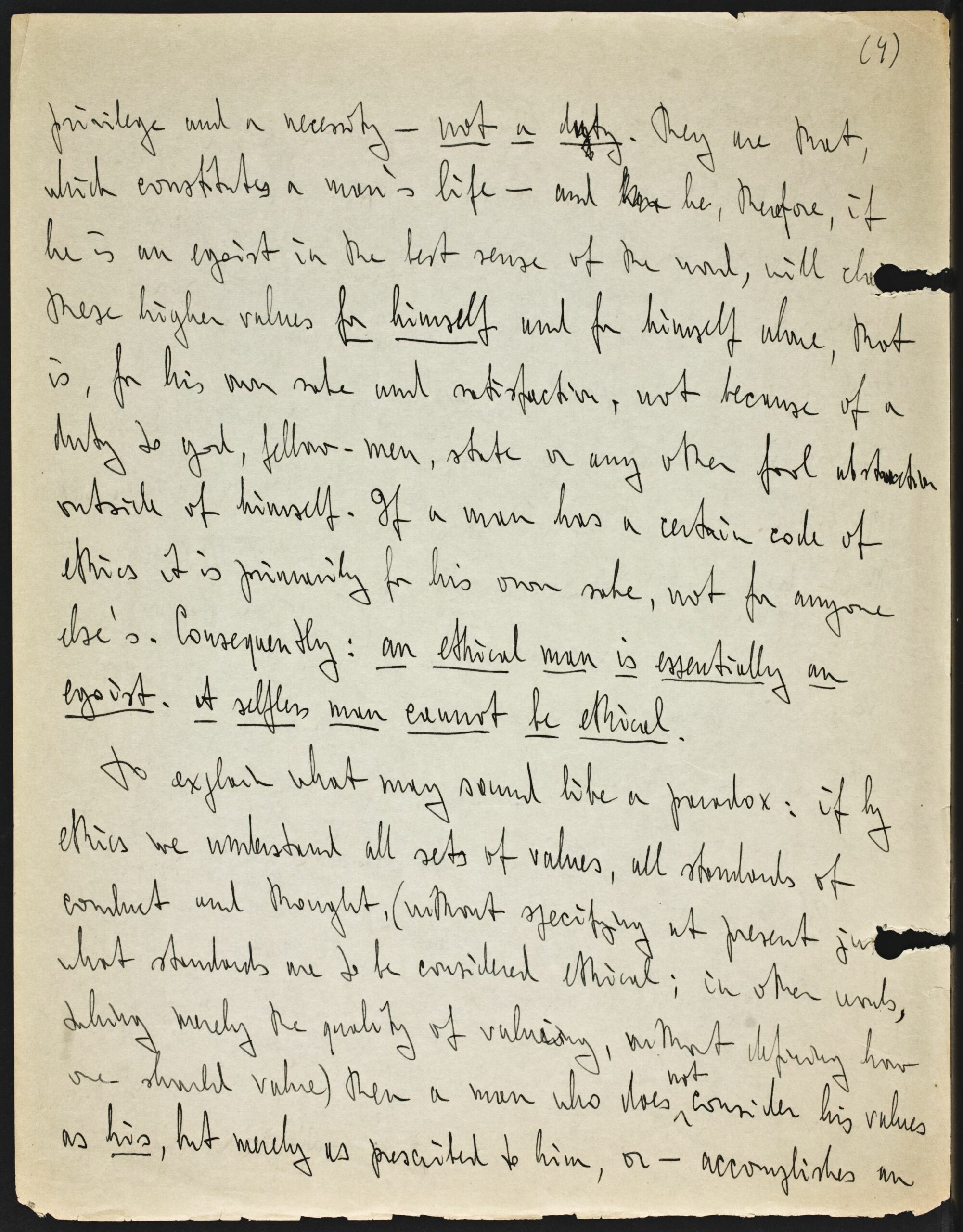

[Page 4]

(4)

privilege and a necessity – not a duty. They are that, which constitutes a man’s life – and [illegible][?here] he, therefore, if he is an egoist in the best sense of the word, will ch[oose or erish] these higher values for himself and for himself alone, that is, for his own sake and satisfaction, not because of a duty to god, fellow-men, state or any other fool abstraction outside of himself. If a man has a certain code of ethics it is primarily for his own sake, not for anyone else’s. Consequently: an ethical man is essentially an egoist. A selfless man cannot be ethical.

To explain what may sound like a paradox : if by ethics we understand all sets of values, all standards of conduct and thought, (without specifying at present just what standards are to be considered ethical; in other words, taking merely the quality of valuing, without defining how one should value) then a man who does not consider his values as his, but merely as prescribed to him, or – accomplishes an

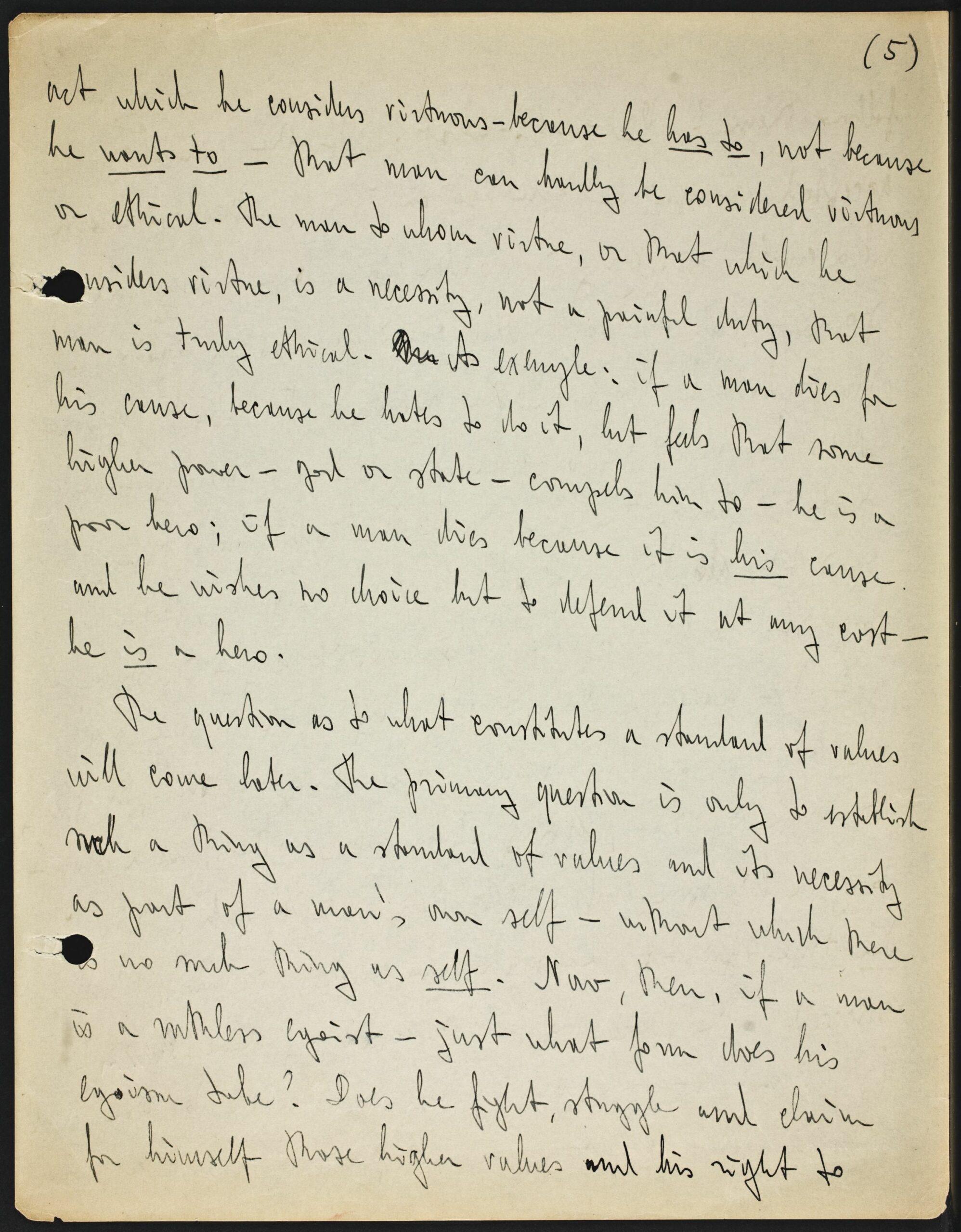

[Page 5]

(5)

act which he considers virtuous – because he has to, not because he wants to – that man can hardly be considered virtuous or ethical. The man to whom virtue, or that which he considers virtue, is a necessity, not a painful duty, that man is truly ethical. [?The] As example: if a man dies for his cause, because he hates to do it, but feels that some higher power – god or state – compels him to – he is a poor hero; if a man dies because it is his cause and he wishes no choice but to defend it at any cost – he is a hero.

The question as to what constitutes a standard of values will come later. The primary question is only to establish such a thing as a standard of values and its necessity as part of a man’s own self – without which there is no such thing as self. Now, then, if a man is a ruthless egoist – just what form does his egoism take? Does he fight, struggle and claim for himself those higher values and his right to

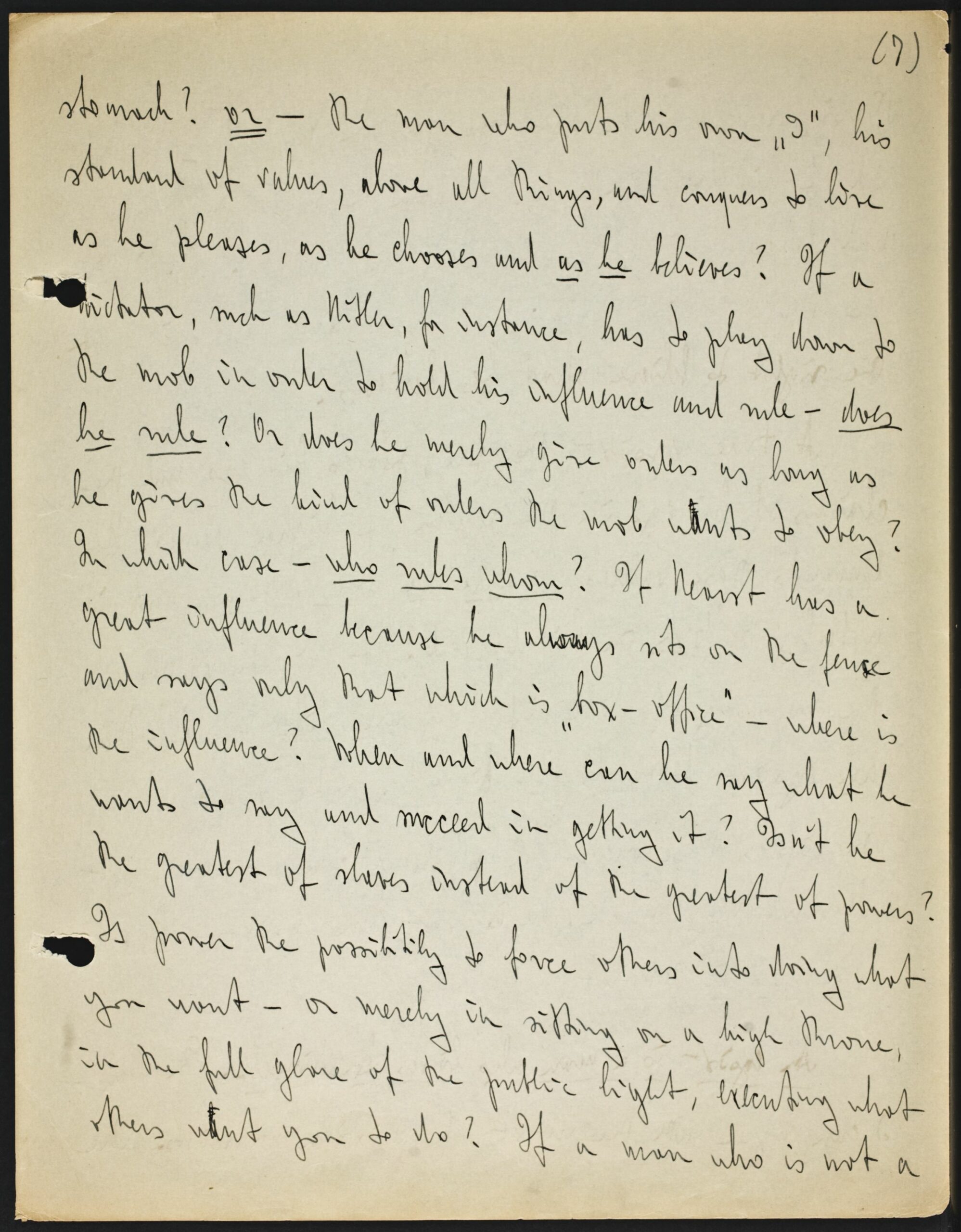

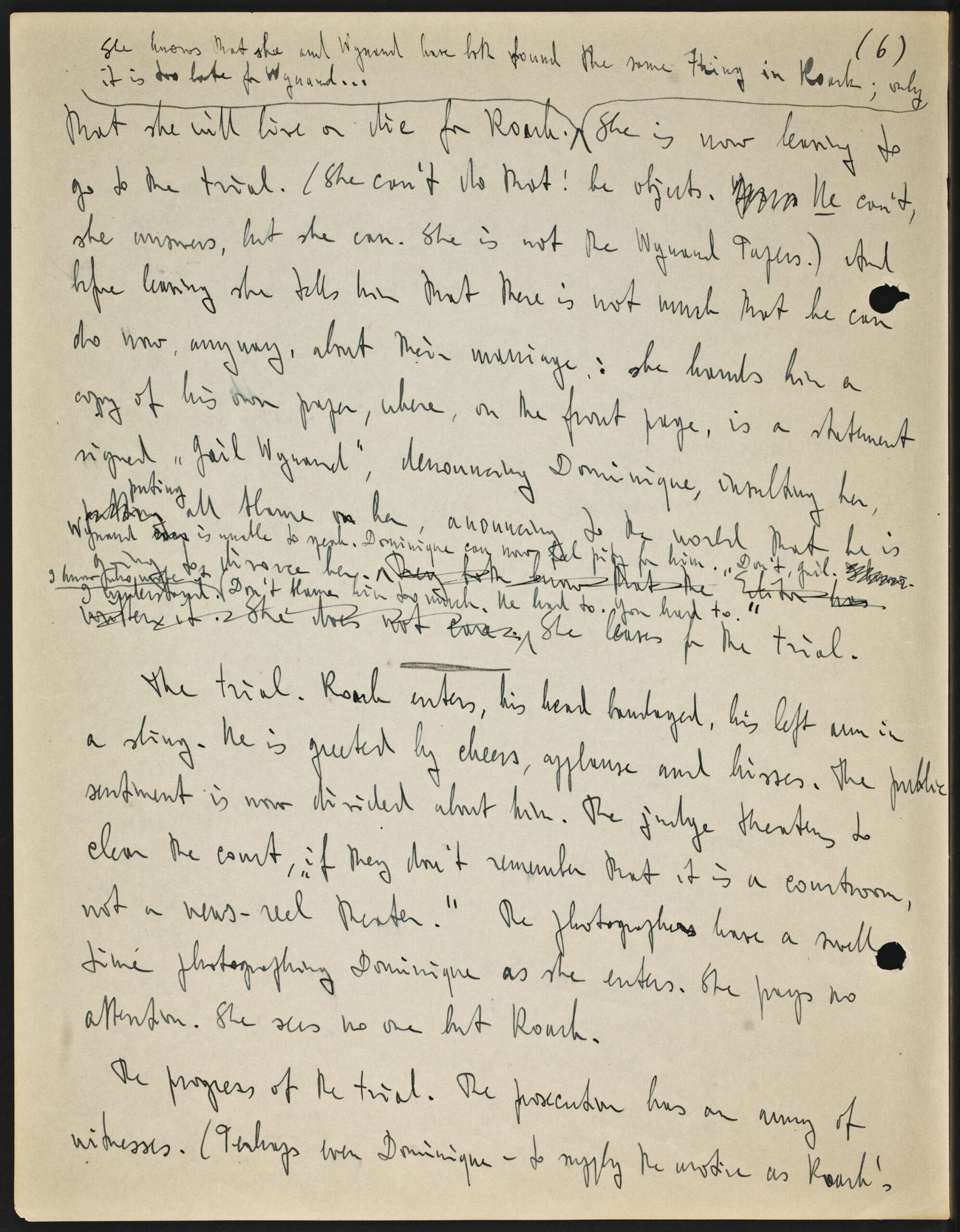

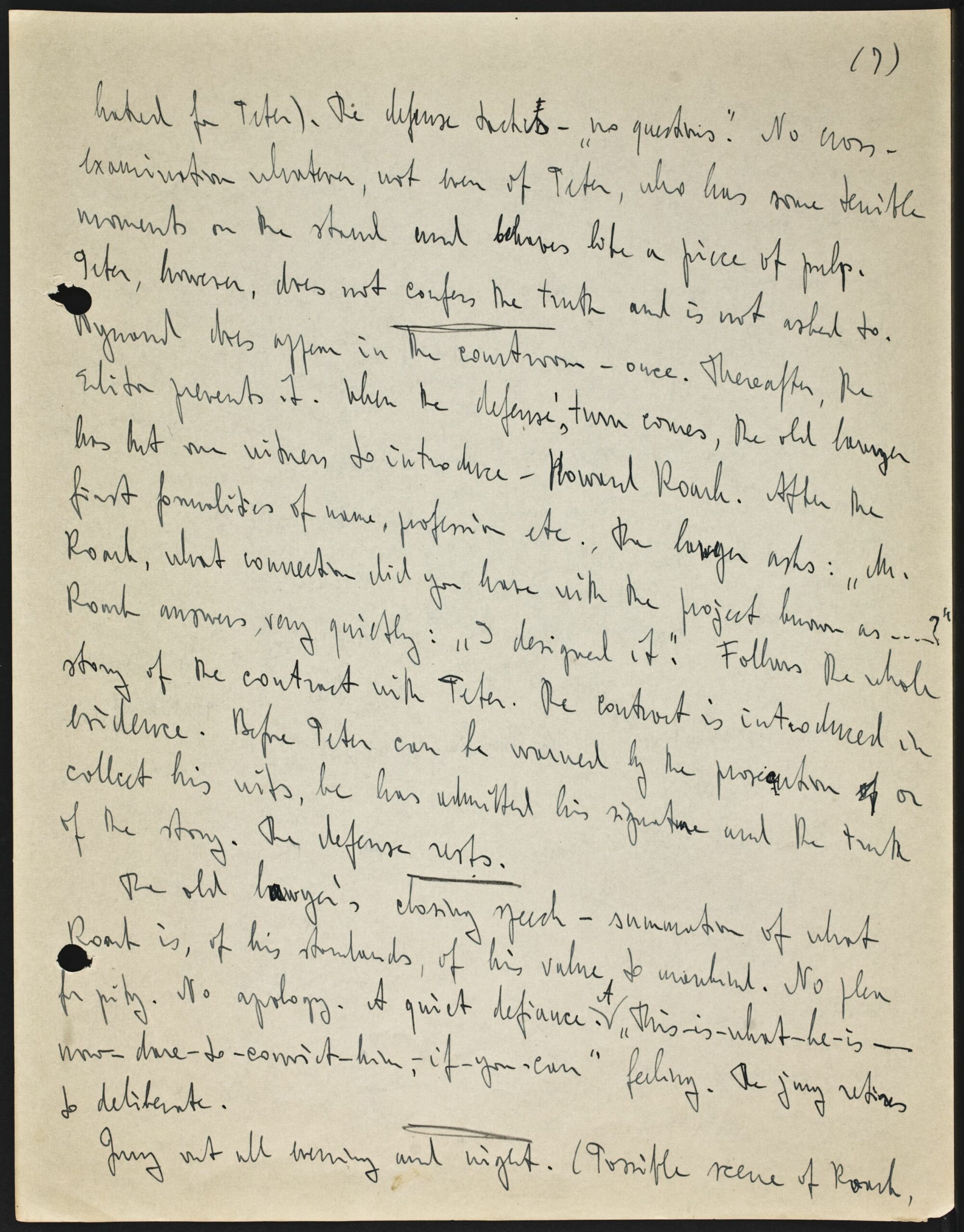

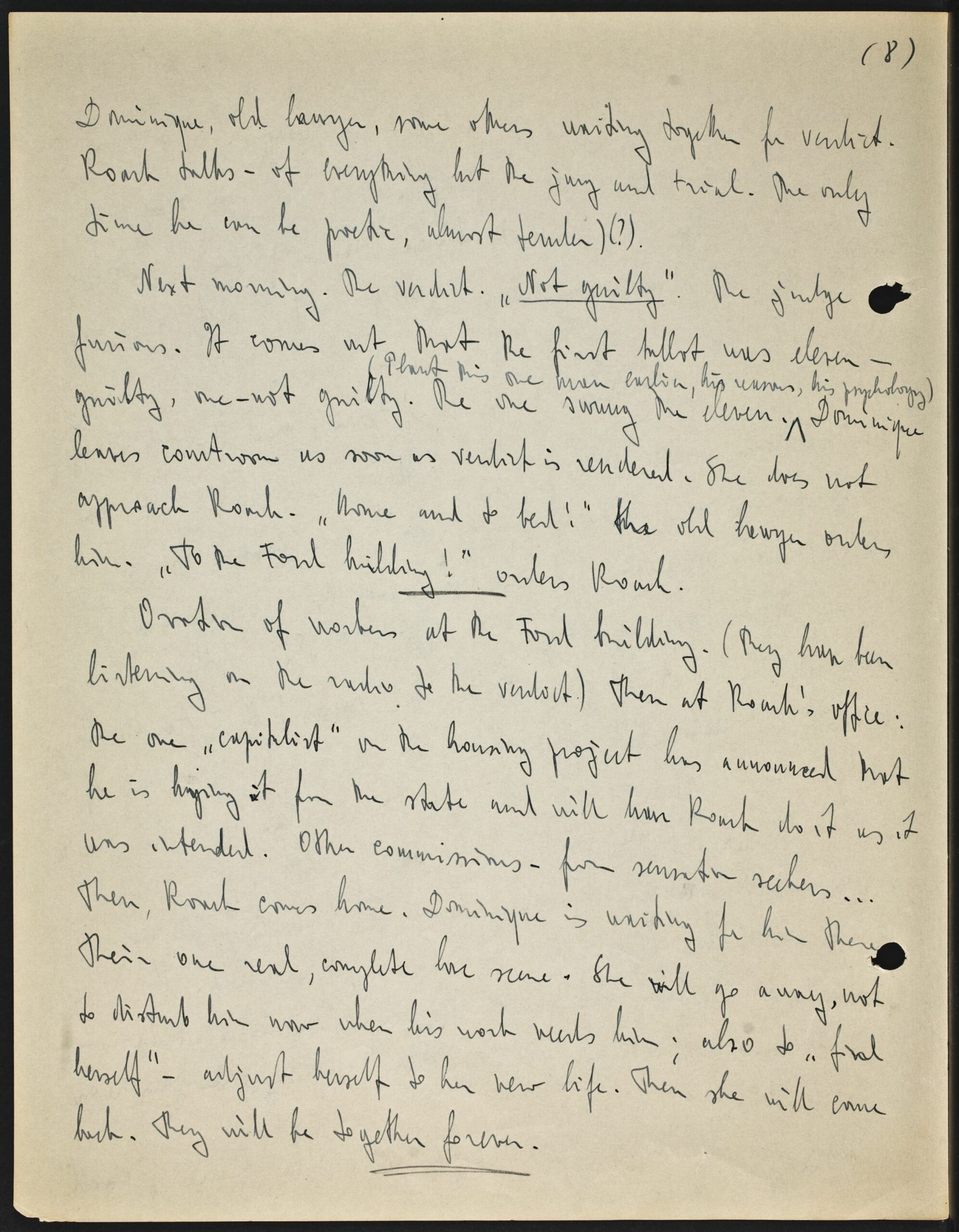

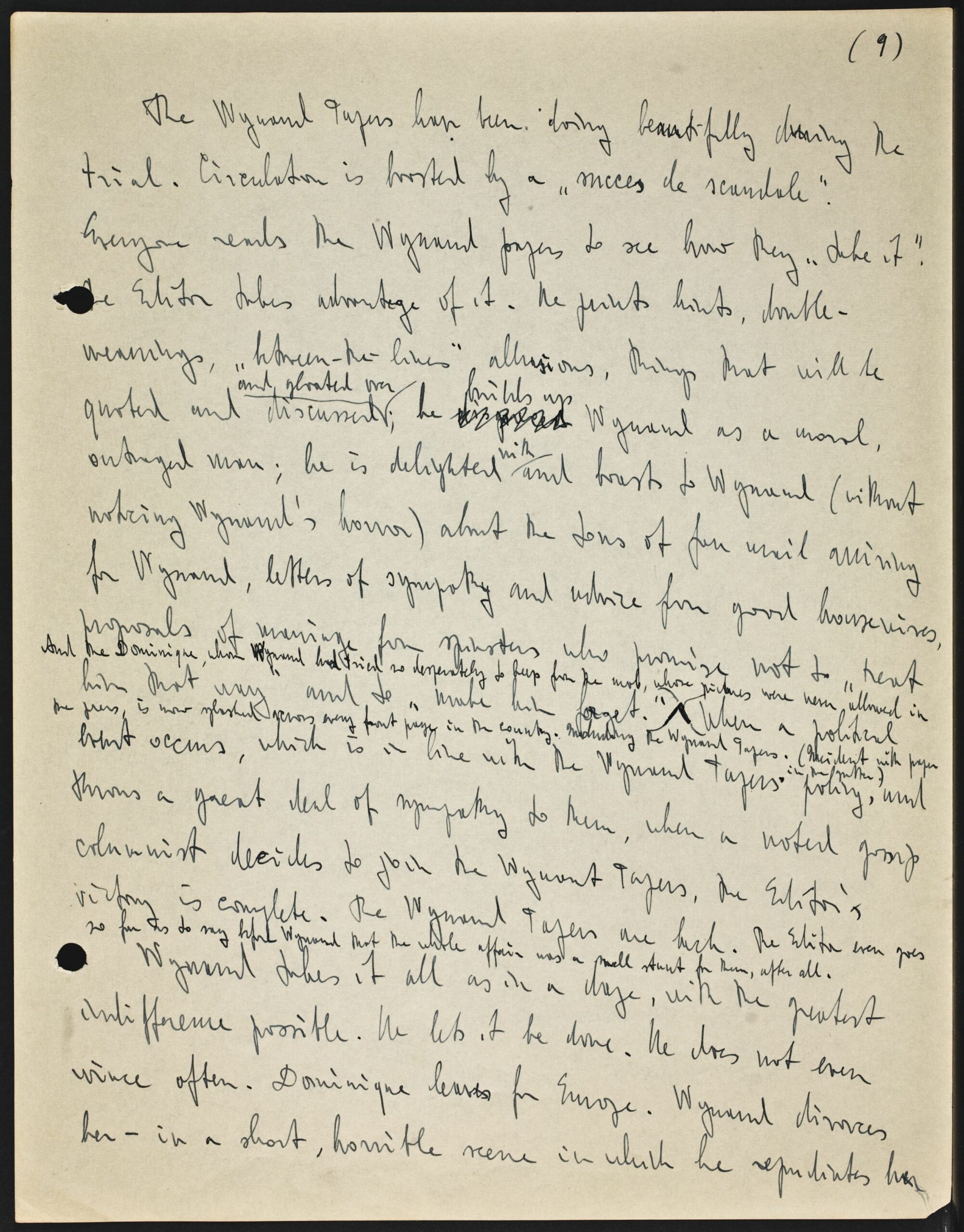

[Page 6]

(6)

follow them? Or – ???–what? If the generally accepted example of pure egoism is a ruthless financier who crushes everything in order to obtain money and power – can he be trully considered as an egoist? What does he do with the money? To what purpose does he use the power? Doesn’t he merely – and that is always the case with the conventional type of egoist – [?alw] give up all standards of value, those prescribed to him as well as his own, if any – in order to get the money? Doesn’t he play down to the mob in every sense and manner, encouraging its vices, sacrificing his own opinions, serving others, always others, as a slave – to gain his own ends? Well then – what ends? Who [?is] the true egoist: the man who crushes his own “I” to succeed with others, to fool them, betray them, [?finish] kill them – but still live as they want him to live and conquer to the extent of a home, a yacht and a full

[Page 7]

(7)

stomach? or – the man who puts his own “I”, his standard of values, above all things, and conquers to live as he pleases, as he chooses and as he believes? If a dictator, such as Hitler, for instance, has to play down to the mob in order to hold his influence and rule – does he rule? Or does he merely give orders as long as he gives the kind of orders the mob wants to obey? In which case – who rules whom? If Hearst has a great influence because he always sits on the fence and says only that which is “box-office” – where is the influence? When and where can he say what he wants to say and succeed in getting it? Isn’t he the greatest of slaves instead of the greatest of powers? Is power the possibility to force others into doing what you want – or merely in sitting on a high throne, in the full glare of the public light, executing what others want you to do? If a man who is not a

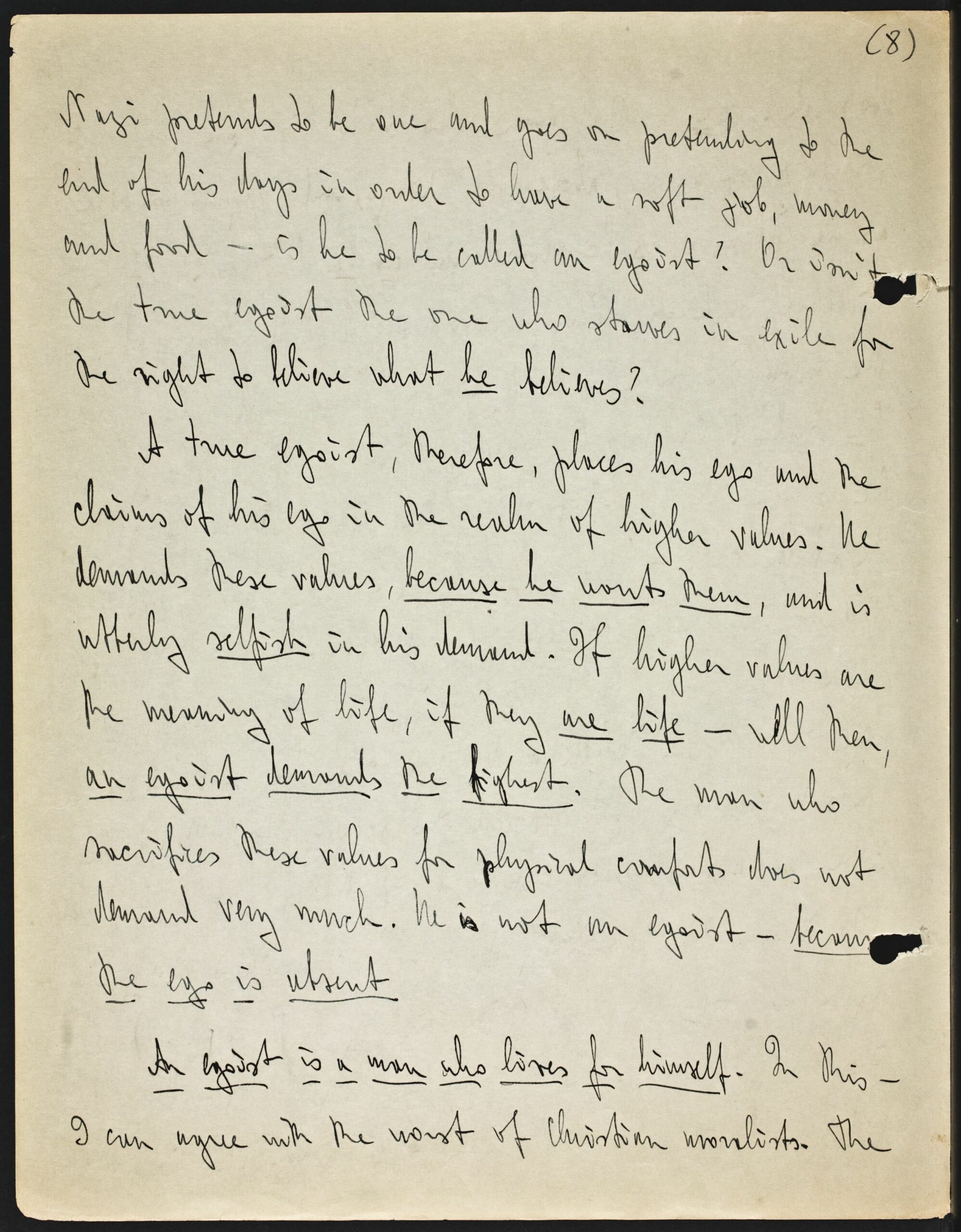

[Page 8]

(8)

Nazi pretends to be one and goes on pretending to the end of his days in order to have a soft job, money and food – is he to be called an egoist? Or isn’t the true egoist the one who starves in exile for the right to believe what he believes?

A true egoist, therefore, places his ego and the claims of his ego in the realm of higher values. He demands these values, because he wants them, and is utterly selfish in his demand. If higher values are the meaning of life, if they are life – well then, an egoist demands the highest. The man who sacrifices these values for physical comforts does not demand very much. He is not an egoist – because the ego is absent

An egoist is a man who lives for himself. In this – I can agree with the worst of Christian moralists. The

[Page 9]

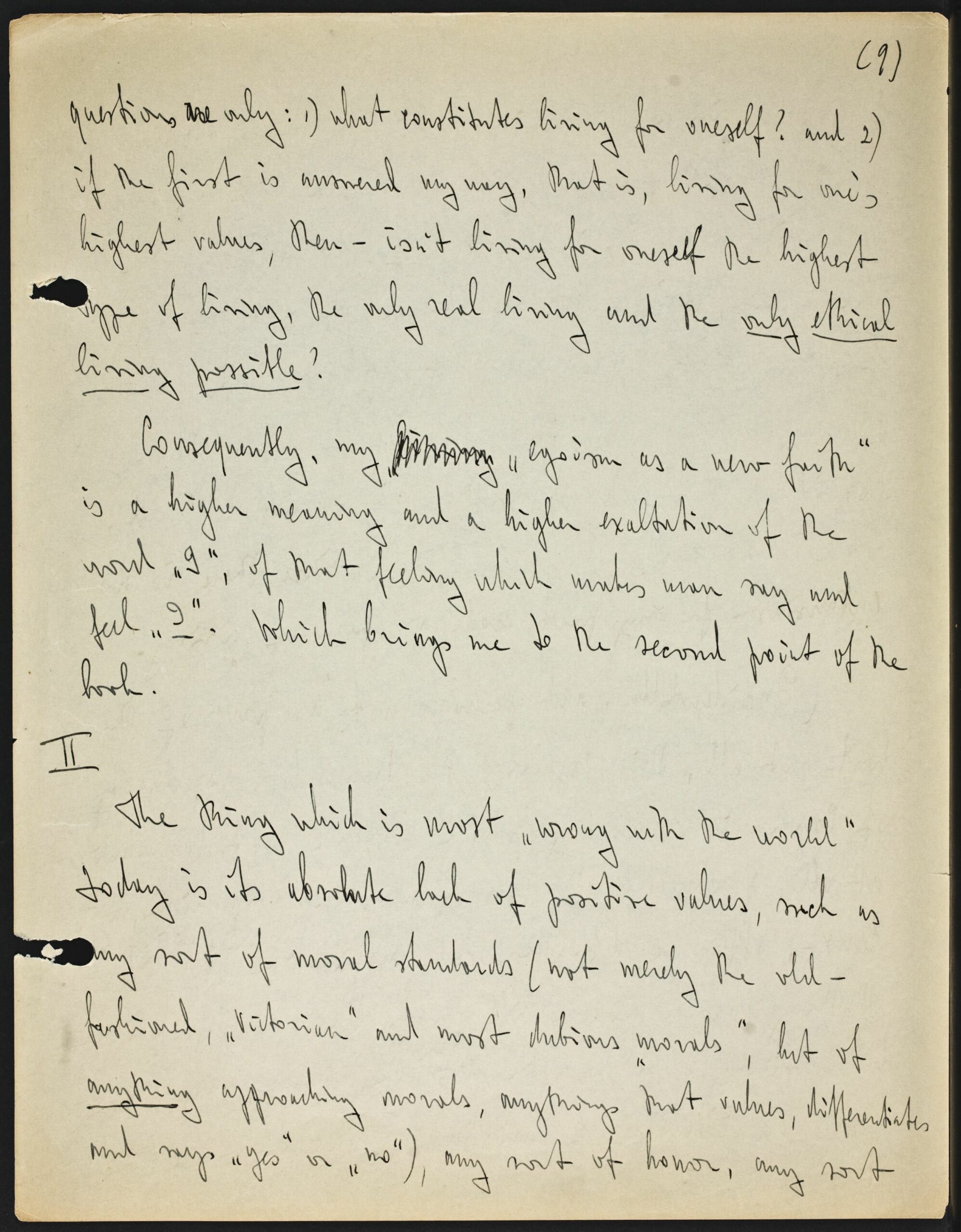

(9)

questions is are only: 1) what constitutes living for oneself? and 2) if the first is answered my way, that is, living for one’s highest values, then – isn’t living for oneself the highest type of living, the only real living and the only ethical living possible?

Consequently, my “living “egoism as a new faith” is a higher meaning and a higher exaltation of the word “I”, of that feeling which makes man say and feel “I”. Which brings me to the second point of the book.

II

The thing which is most “wrong with the world” today is its absolute lack of positive values, such as [?any] sort of moral standards (not merely the old-fashioned, “Victorian” and most dubious “morals”, but of anything approaching morals, anything that values, differentiates and says “yes” or “no”), any sort of honor, any sort

[Page 10]

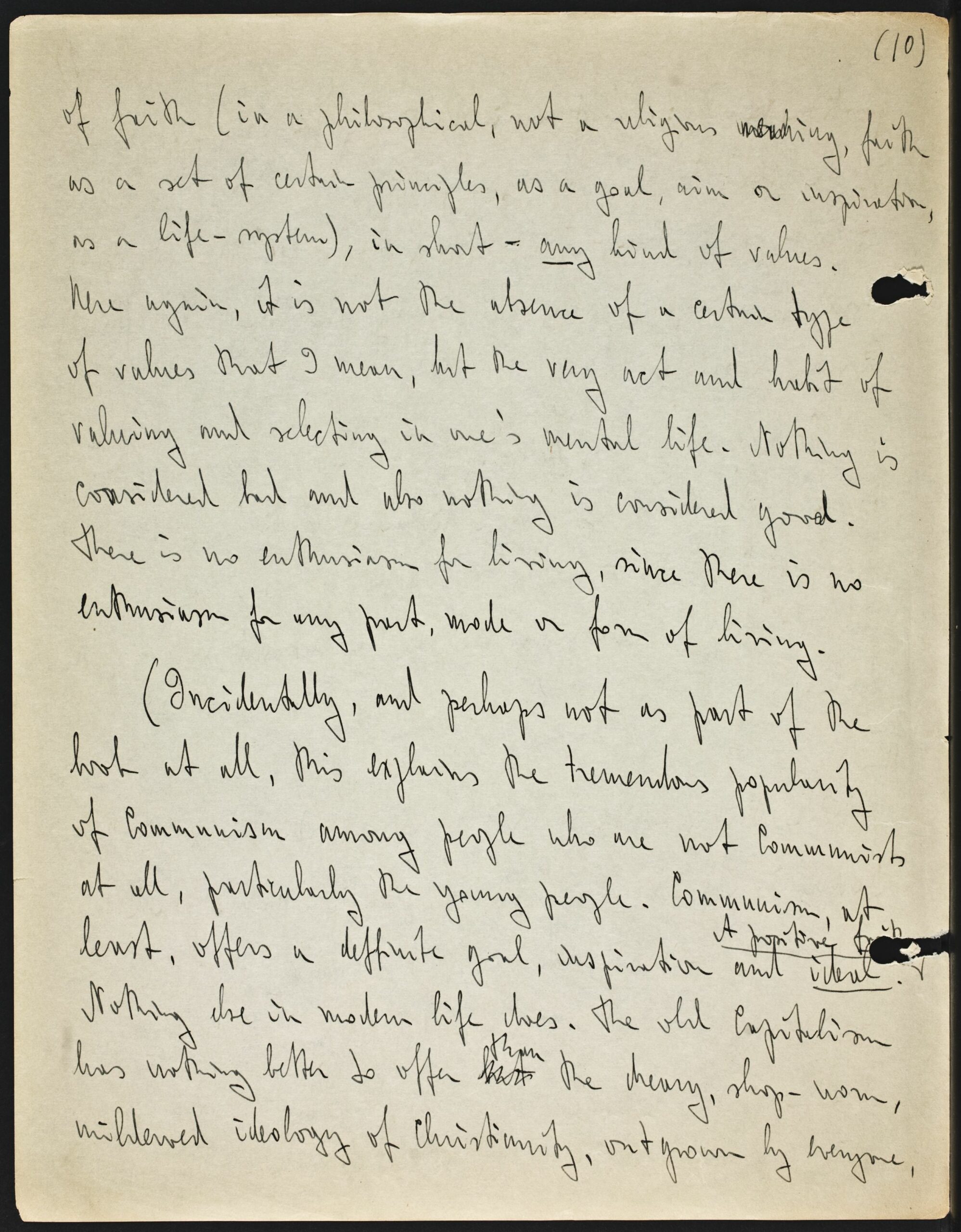

(10)

of faith (in a philosophical, not a religious [?meaning], faith as a set of certain principles, as a goal, aim or inspiration, as a life-system), in short – any kind of values. Here again, it is not the absence of a certain type of values that I mean, but the very act and habit of valuing and selecting in one’s mental life. Nothing is considered bad and also nothing is considered good. There is no enthusiasm for living, since there is no enthusiasm for any part, mode or form of living.

(Incidentally, and perhaps not as part of the book at all, this explains the tremendous popularity of Communism among people who are not Communists at all, particularly the young people. Communism, at least, offers a definite goal, inspiration and ideal. A positive faith Nothing else in modern life does. The old Capitalism has nothing better to offer but than the dreary, shop-worn, mildewed ideology of Christianity, outgrown by everyone,

[Page 11]

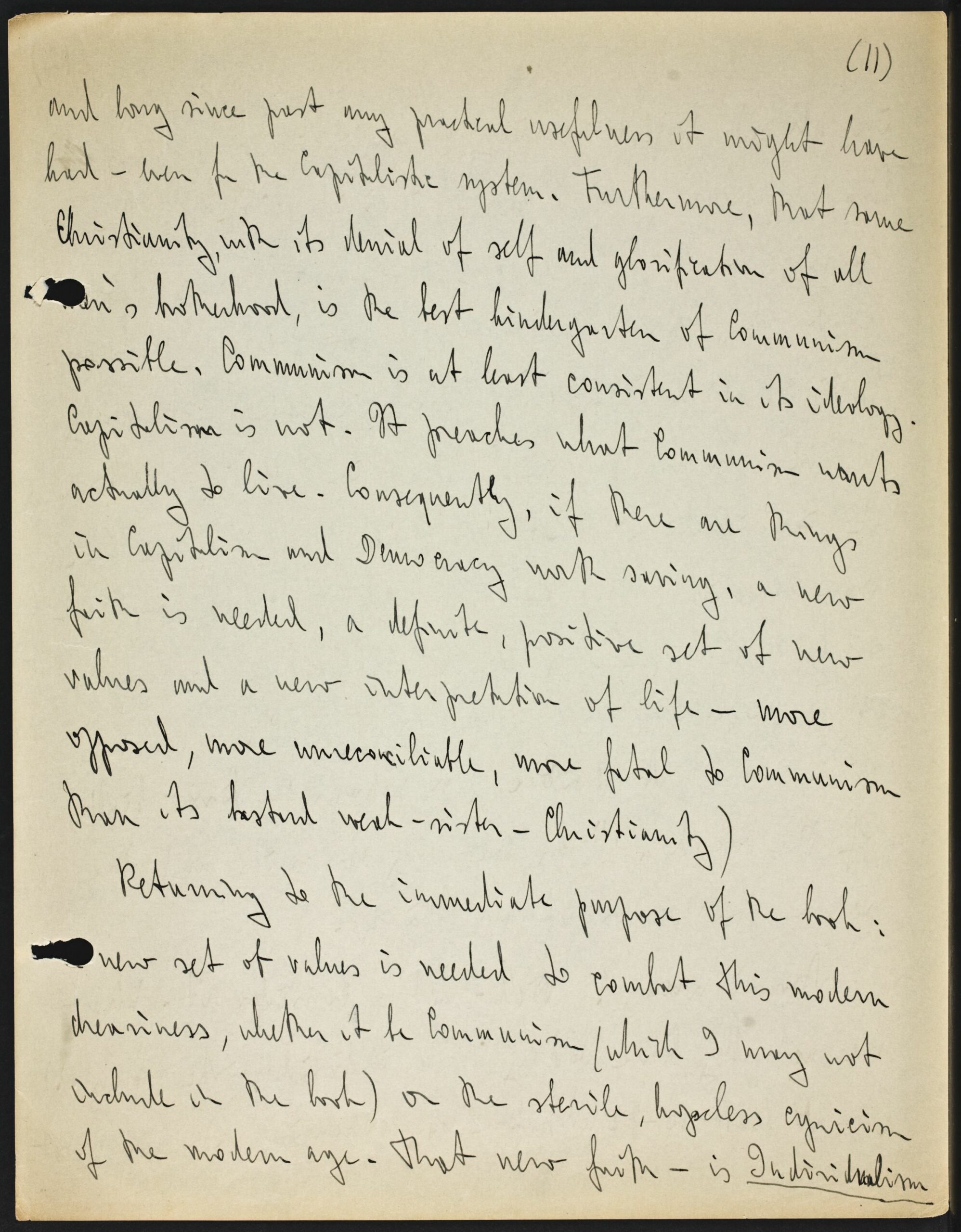

(11)

and long since past any practical usefulness it might have had – even for the Capitalistic system. Furthermore, that same Christianity, with its denial of self and glorification of all [?man]’s brotherhood, is the best kindergarten of Communism possible. Communism is at least consistent in its ideology. Capitalism is not. It preaches what Communism wants actually to live. Consequently, if there are things in Capitalism and Democracy worth saving, a new faith is needed, a definite, positive set of new values and a new interpretation of life – more opposed, more unreconciliable, more fatal to Communism than its bastard weak-sister – Christianity)

Returning to the immediate purpose of the book: [?A] new set of values is needed to combat this modern dreariness, whether it be Communism (which I may not include in the book) or the sterile, hopeless cynicism of the modern age. That new faith – is Individualism

[Page 12]

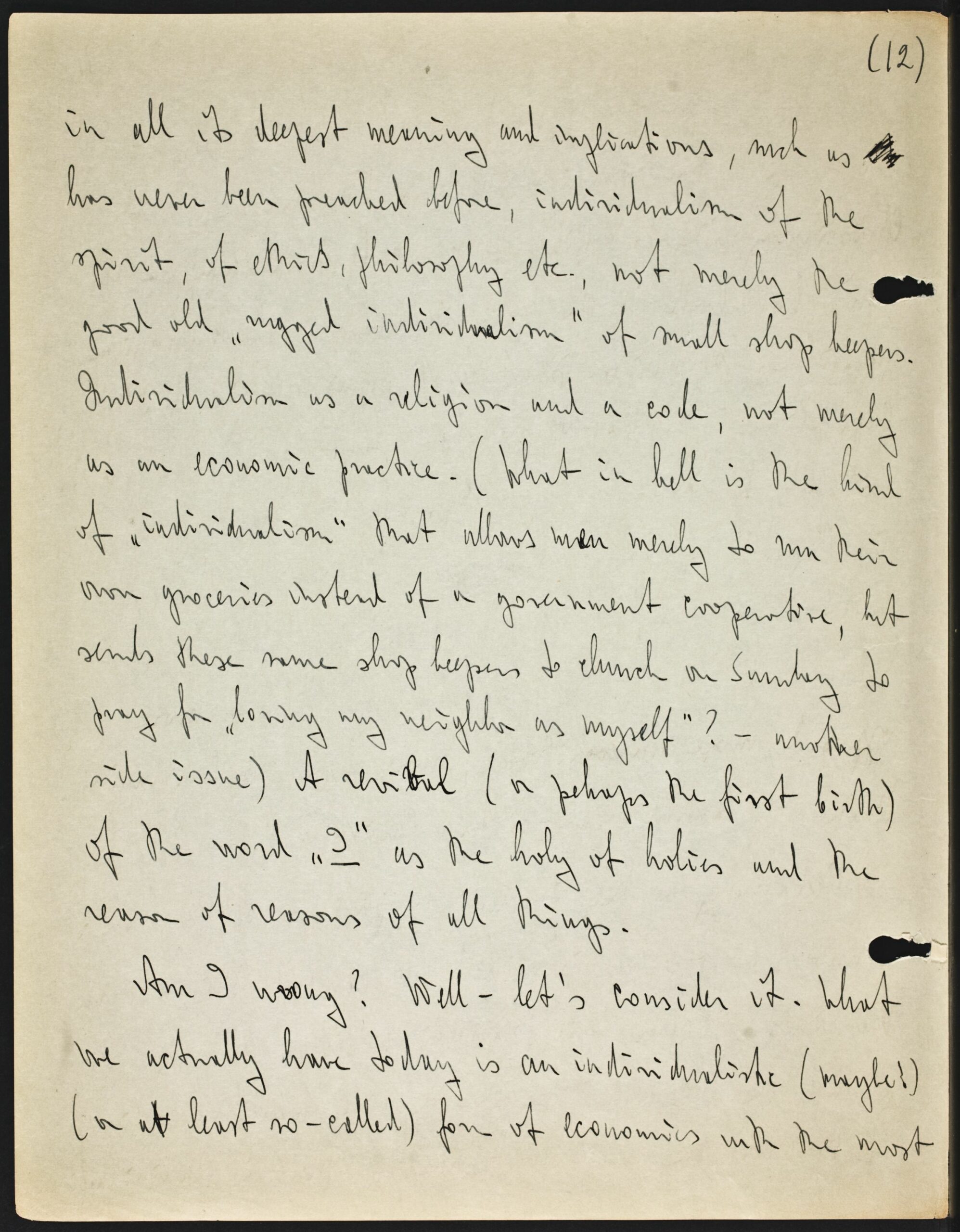

(12)

in all its deepest meaning and implications, such as [?ot] has never been preached before, individualism of the spirit, of ethics, philosophy etc., not merely the good old “rugged individualism” of small shop keepers. Individualism as a religion and a code, not merely as an economic practice. (What in hell is the kind of “individualism” that allows men merely to run their own groceries instead of a government cooperative, but sends these same shop keepers to church on Sunday to pray for “loving my neighbor as myself”? – another side issue) A revival (or perhaps the first birth) of the word “I” as the holy of holies and the reason of reasons of all things.

Am I wrong? Well – let’s consider it. What we actually have today is an individualistic (maybe!) (or at least so-called) form of economics with the most

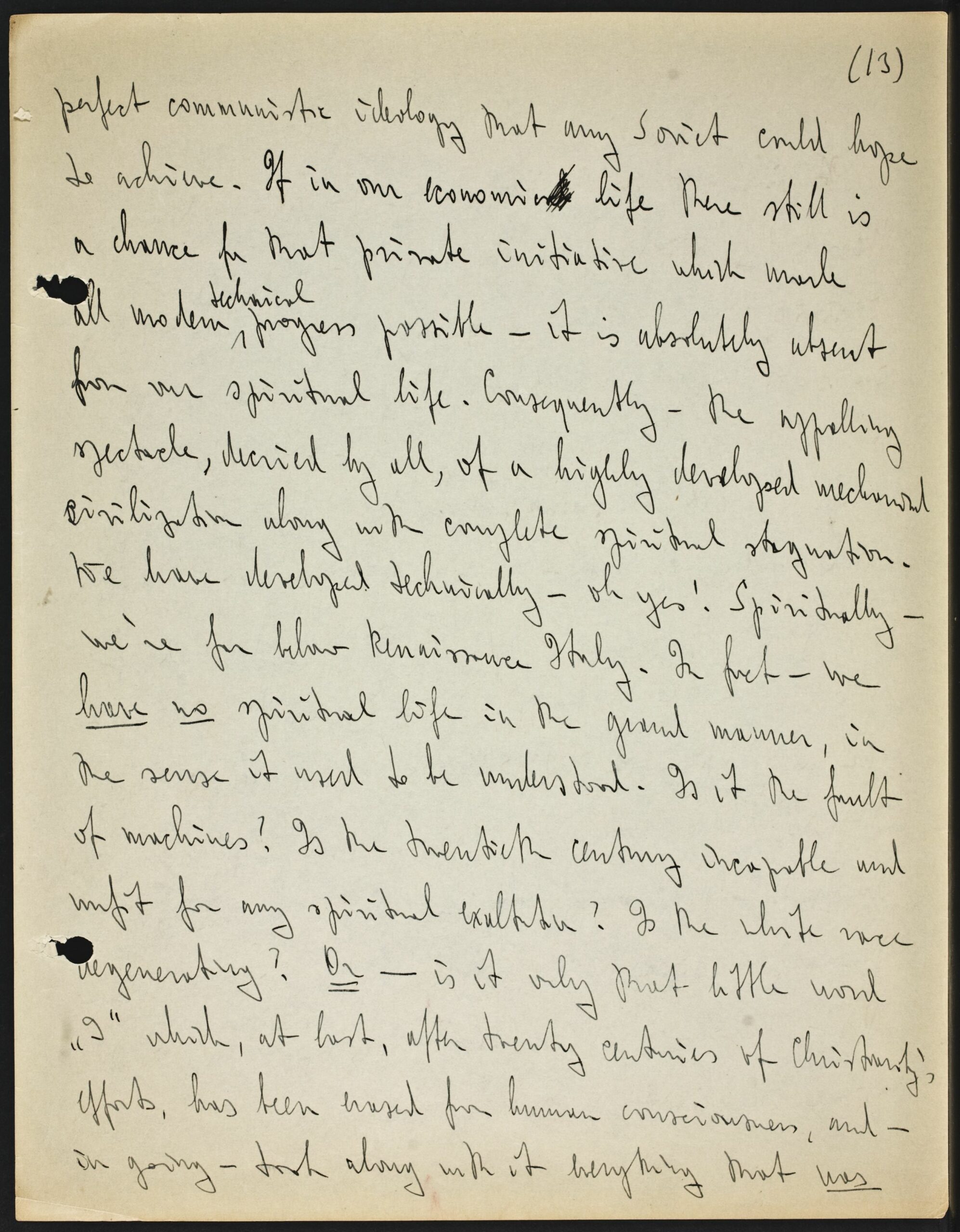

[Page 13]

(13)

perfect communistic ideology that any Soviet could hope to achieve. If in our economical life there still is a chance for that private initiative which made all modern technical progress possible – it is absolutely absent from our spiritual life. Consequently – the appalling spectacle, decried by all, of a highly developed mechanical civilization along with complete spiritual stagnation. We have developed technically – oh yes! Spiritually – we’re far below Renaissance Italy. In fact – we have no spiritual life in the grand manner, in the sense it used to be understood. Is it the fault of machines? Is the twentieth century incapable and unfit for any spiritual exaltation? Is the white race degenerating? Or – is it only that little word “I” which, at last, after twenty centuries of Christianity’s efforts, has been erased from human consciousness, and – in going – took along with it everything that was

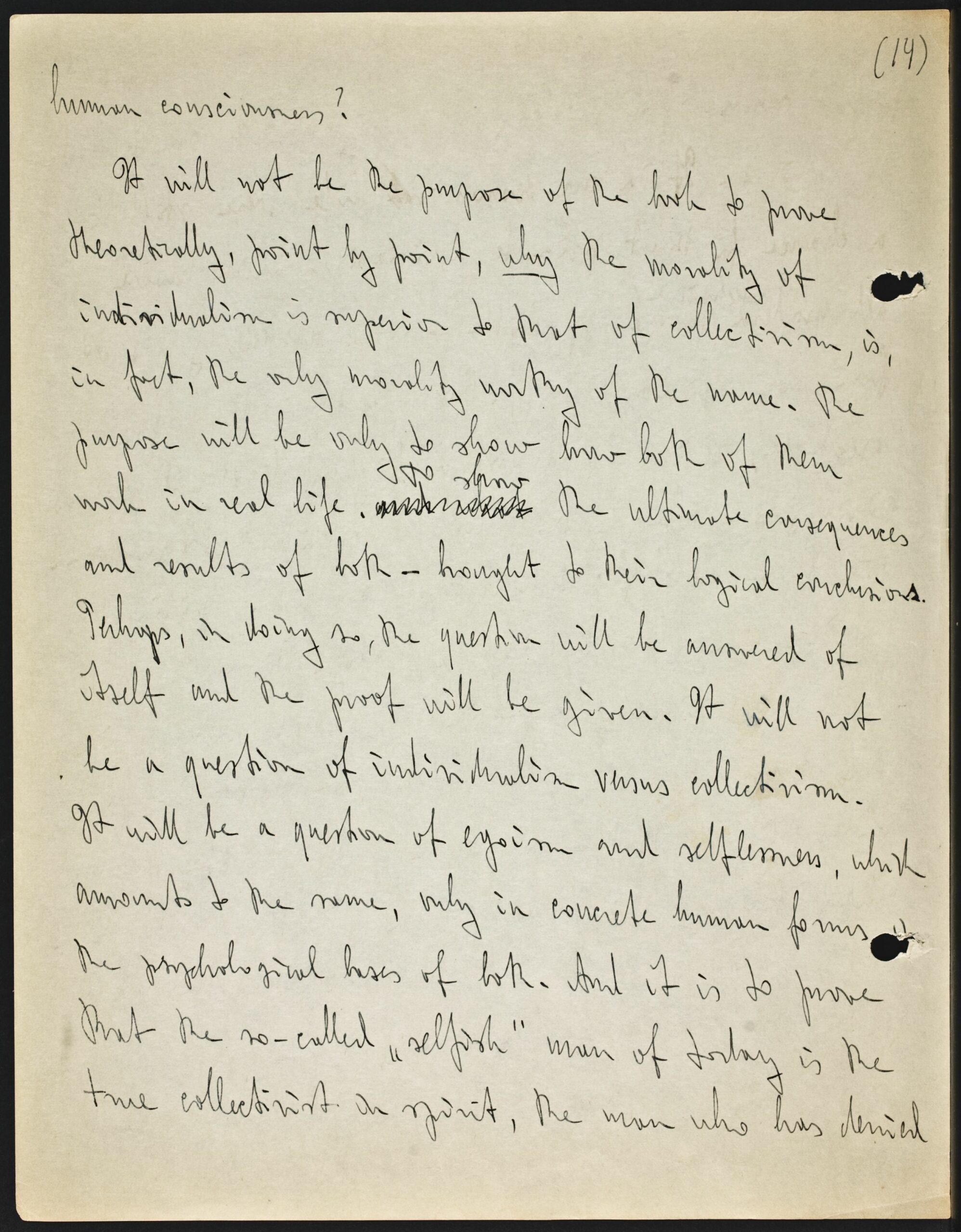

[Page 14]

(14)

human consciousness?

It will not be the purpose of the book to prove theoretically, point by point, why the morality of individualism is superior to that of collectivism, is, in fact, the only morality worthy of the name. The purpose will be only to show how both of them work in real life. and what To show the ultimate consequences and results of both – brought to their logical conclusions. Perhaps, in doing so, the question will be answered of itself and the proof will be given. It will not be a question of individualism versus collectivism. It will be a question of egoism and selflessness, which amounts to the same, only in concrete human forms [?of] the psychological bases of both. And it is to prove that the so-called “selfish” man of today is the true collectivist in spirit, the man who has denied

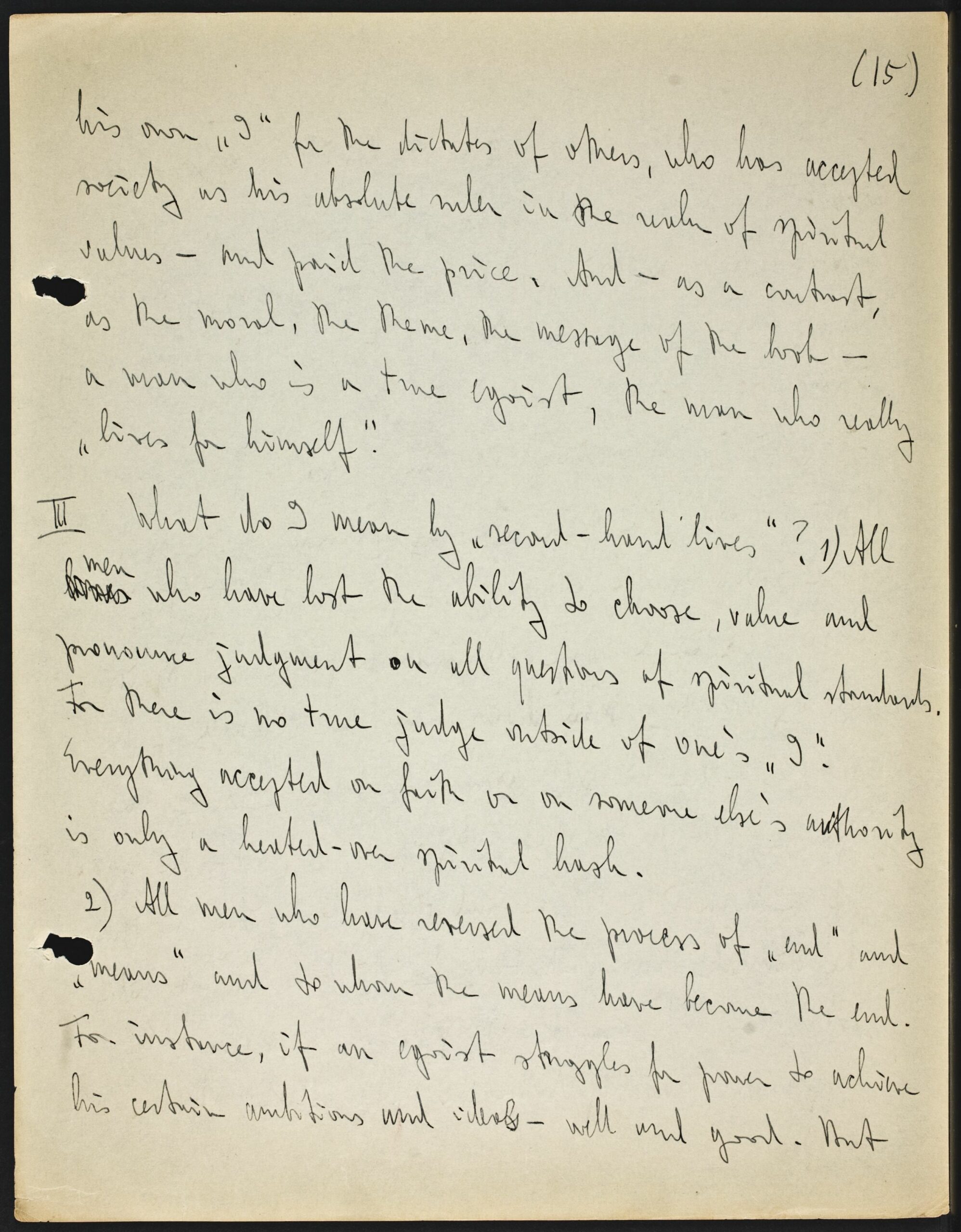

[Page 15]

(15)

his own “I” for the dictates of others, who has accepted society as his absolute ruler in the realm of spiritual values – and paid the price. And – as a contrast, as the moral, the theme, the message of the book – a man who is a true egoist, the man who really “lives for himself”.

III What do I mean by “second-hand lives”? 1) All lives men who have lost the ability to choose, value and pronounce judgment on all questions of spiritual standards. For there is no true judge outside of one’s “I”. Everything accepted on faith or on someone else’s authority is only a heated-over spiritual hash.

2) All men who have reversed the process of “end” and “means” and to whom the means have become the end. For instance, if an egoist struggles for power to achieve his certain ambitions and ideals – well and good. But

[Page 16]

(16)

if, in the struggle, he sacrifices his ideals to a merely to accept achieve the power – he is accepting a second-hand substitute, a thing that has no meaning, that brings him no value whatever, but takes his values away instead.

3) (This is the main point, in its most practical applications) All men who, by betraying their egos, live actually for others, not for themselves, live only through others. For instance: if a man struggles for power and achieves it by accepting [?thed] and championing the ideology of the masses – he himself knows that he has no real power, but he has it only in the eyes of the mob. If a man is a crook and cheets to achieve his ends he himself knows that he is dishonest, but will struggle and scramble to preserve a respectable appearance and reputation in the eyes of others. If

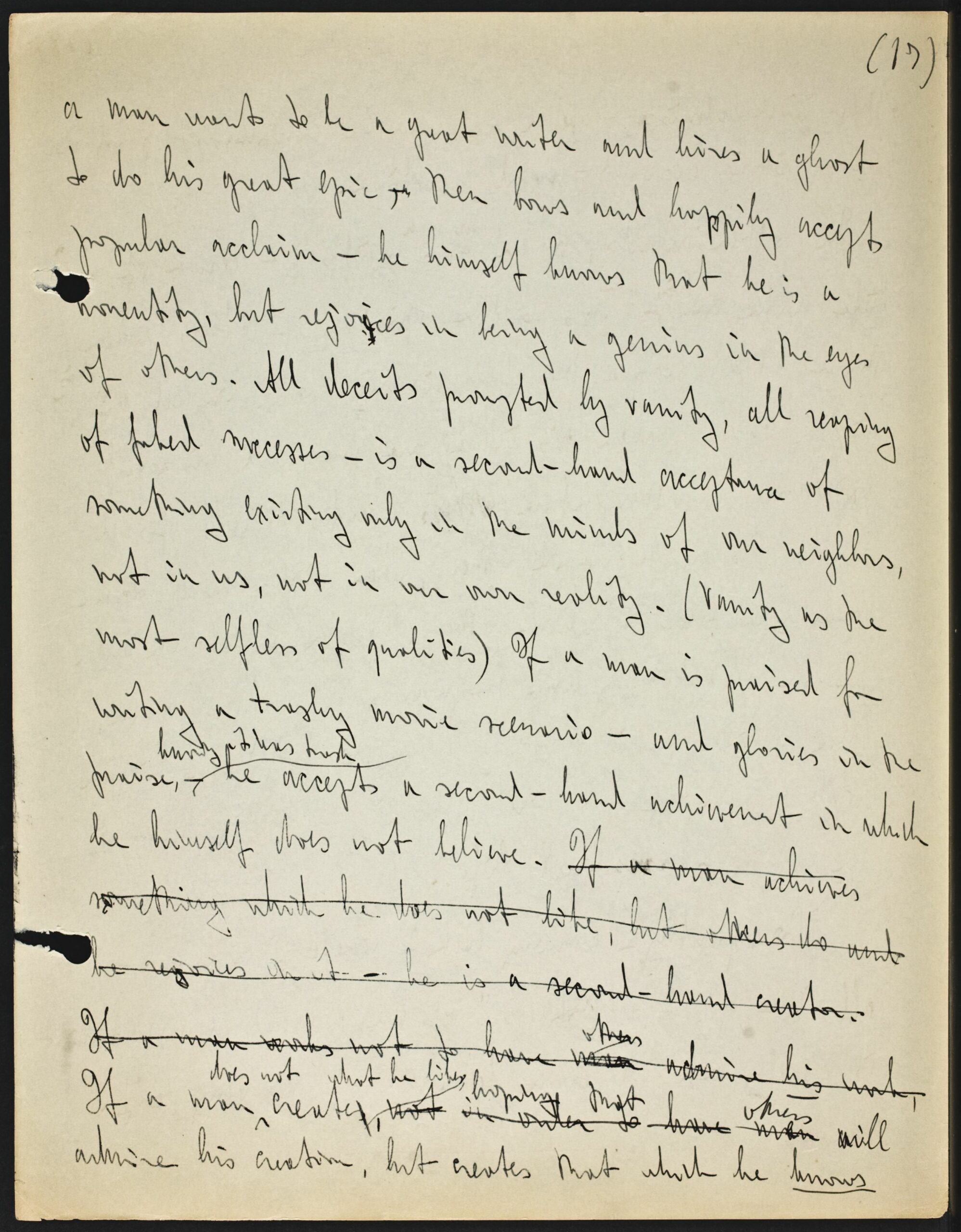

[Page 17]

(17)

a man wants to be a great writer and hires a ghost to do his great epic, – then bows and happily accepts popular acclaim – he himself knows that he is a nonentity, but rejoices in being a genius in the eyes of others. All deceits prompted by vanity, all reaping of faked successes – is a second-hand acceptance of something existing only in the minds of our neighbors, not in us, not in our own reality. (Vanity as the most selfless of qualities) If a man is praised for writing a trashy movie scenario – and glories in the praise, – knowing it was trash he accepts a second-hand achievement in which he himself does not believe. If a man achieves something which he does not like, but others do and he rejoices in it – he is a second-hand creator. If a man works not to have man others admire his work, If a man does not creates what he likes, not in order to hoping that have men others will admire his creation, but creates that which he knows

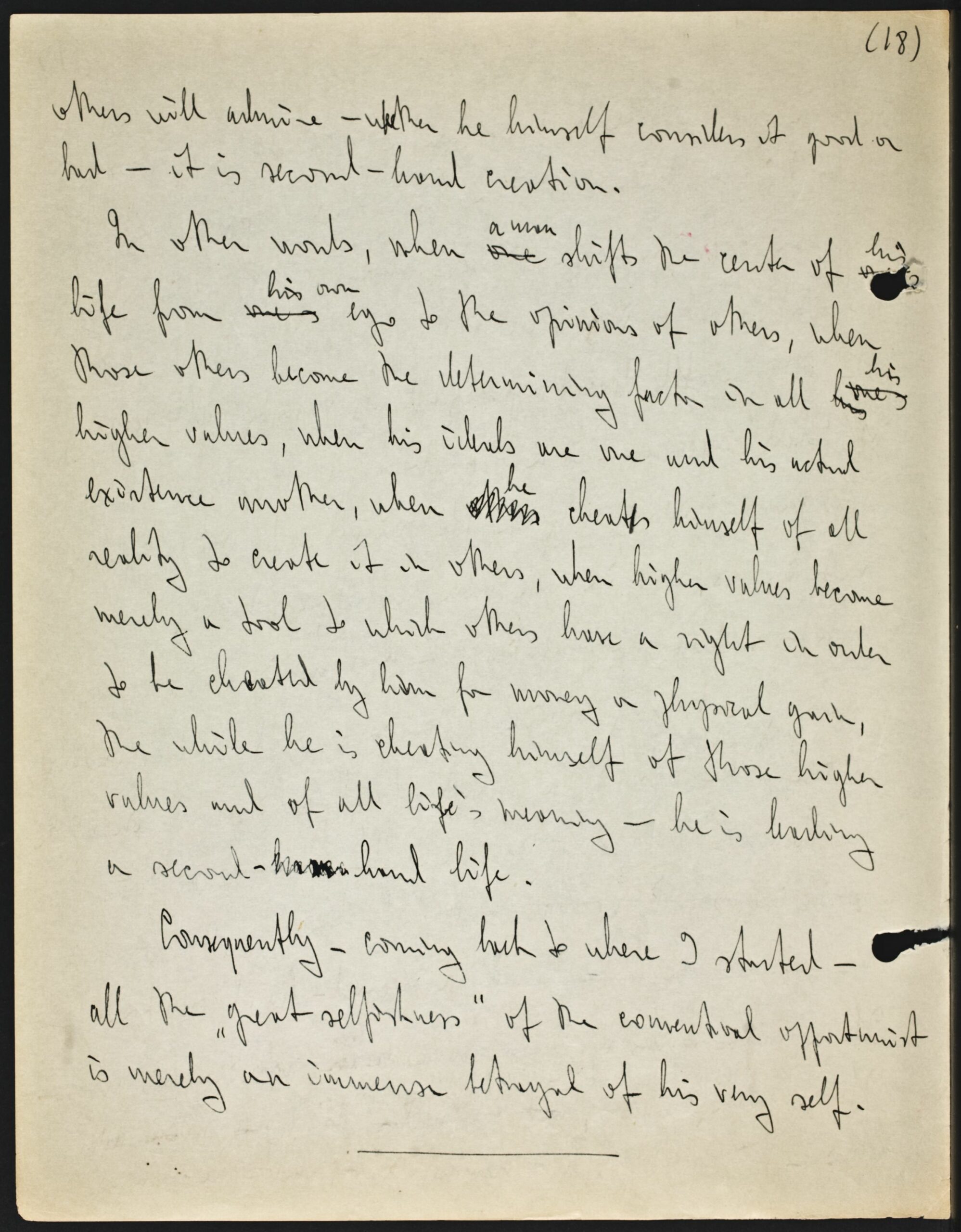

[Page 18]

(18)

others will admire – whether he himself considers it good or bad – it is second-hand creation.

In other words, when one a man shifts the center of one’s his life from one’s his own ego to the opinions of others, when those others become the determining factor in all his one’s his higher values, when his ideals are one and his actual existence another, when others he cheats himself of all reality to create it in others, when higher values become merely a tool to which others have a right in order to be cheated by him for money or physical gain, the while he is cheating himself of those higher values and of all life’s meaning – he is leading a second-[illegible]hand life.

Consequently – coming back to where I started – all the “great selfishness” of the conventional opportunist is merely an immense betrayal of his very self.

[Page 19]

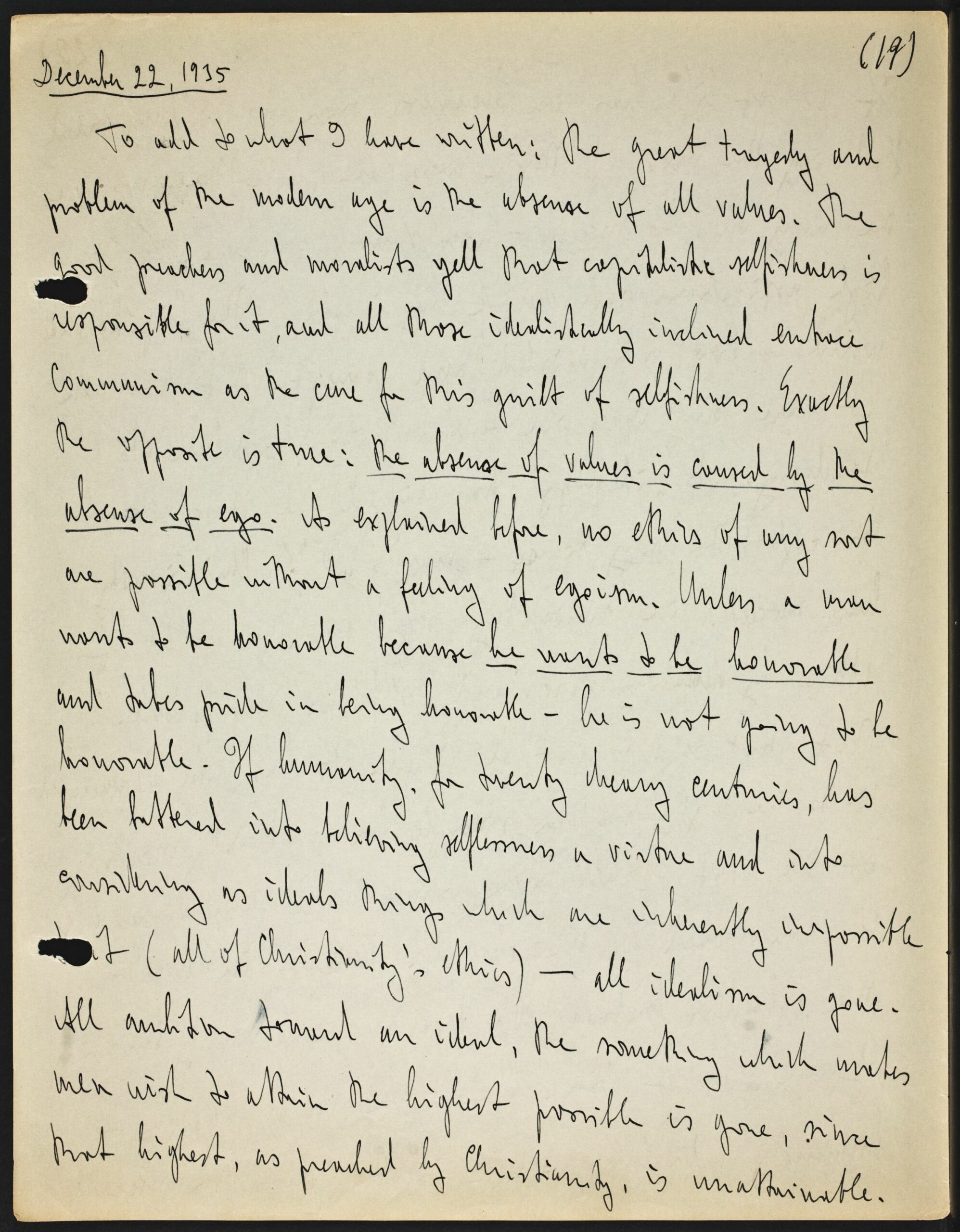

(19)

December 22, 1935

To add to what I have written: the great tragedy and problem of the modern age is the absence of all values. The good preachers and moralists yell that capitalistic selfishness is responsible for it, and all those idealistically inclined embrace Communism as the cure for this guilt of selfishness. Exactly the opposite is true: the absence of values is caused by the absence of ego. As explained before, no ethics of any sort are possible without a feeling of egoism. Unless a man wants to be honorable because he wants to be honorable and takes pride in being honorable – he is not going to be honorable. If humanity, for twenty dreary centuries, has been battered into believing selflessness a virtue and into considering as ideals things which are inherently impossible [?to] it (all of Christianity’s ethics) – all idealism is gone. All ambition toward an ideal, the something which makes men wish to attain the highest possible is gone, since that highest, as preached by Christianity, is unattainable.

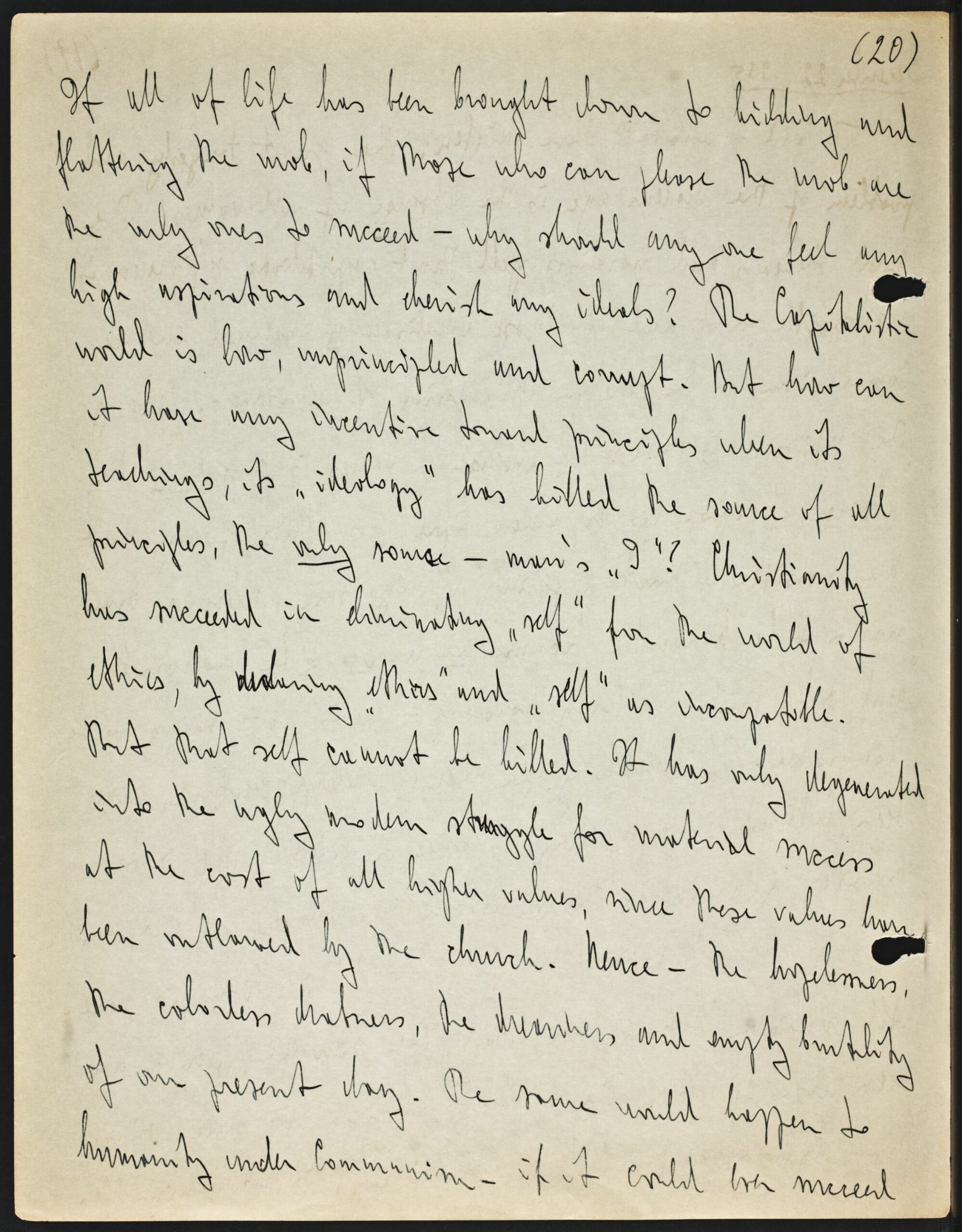

[Page 20]

(20)

If all of life has been brought down to kidding and flattering the mob, if those who can please the mob are the only ones to succeed – why should anyone feel any high aspirations and cherish any ideals? The Capitalistic world is low, unprincipled and corrupt. But how can it have any incentive toward principles when its teachings, its “ideology” has killed the source of all principles, the only source – man’s “I”? Christianity has succeeded in eliminating “self” from the world of ethics, by declaring “ethics” and “self” as incompatible. But that self cannot be killed. It has only degenerated into the ugly modern struggle for material success at the cost of all higher values, since these values have been outlawed by the church. Hence – the hopelessness, the colorless drabness, the dreariness and empty brutality of our present day. The same would happen to humanity under Communism – if it could ever succeed

[Page 21]

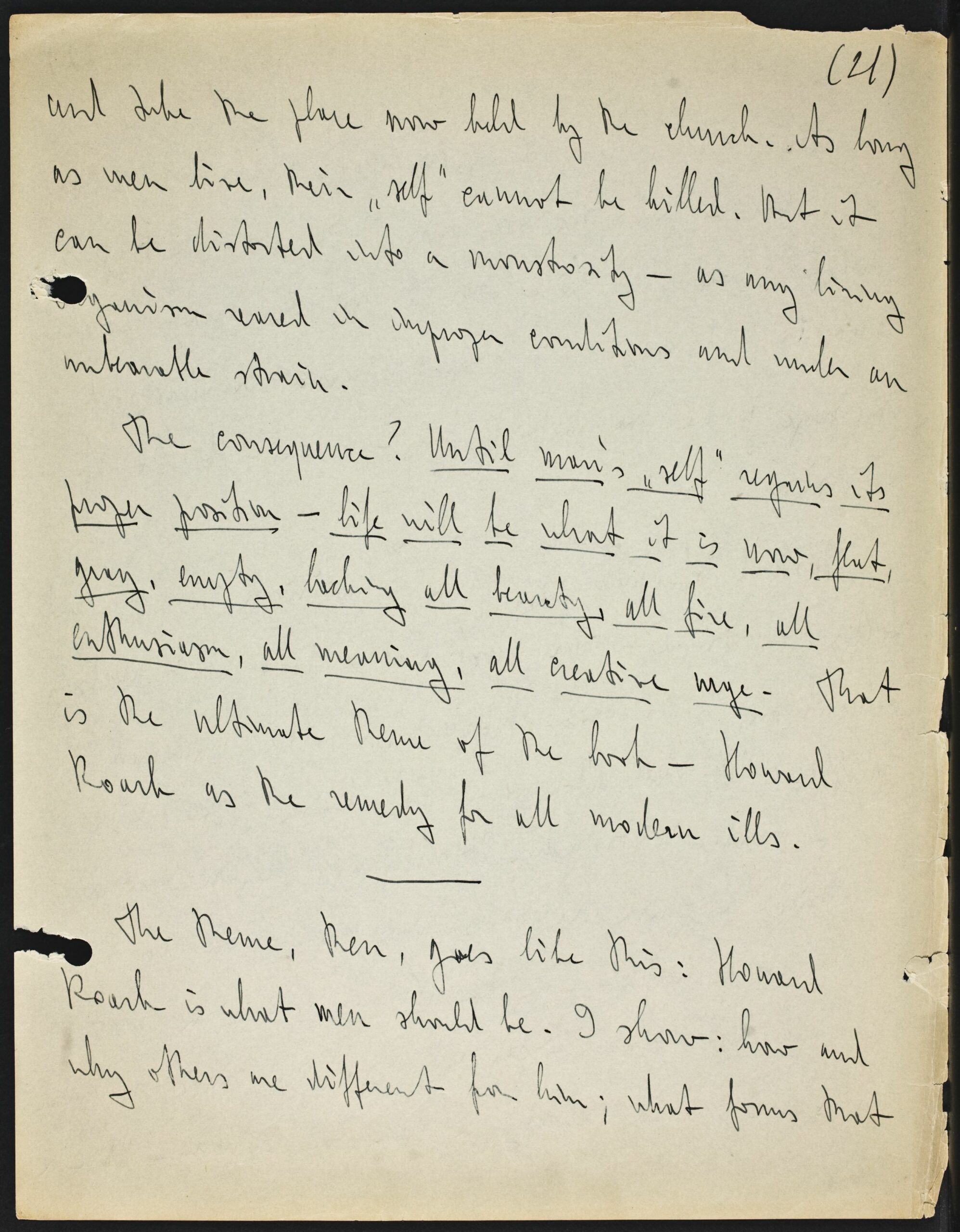

(21)

and take the place now held by the church. As long as men live, their “self” cannot be killed. But it can be distorted into a monstrosity – as any living organism reared in improper conditions and under an unbearable strain.

The consequence? Until man’s “self” regains its proper position – life will be what it is now, flat, gray, empty, lacking all beauty, all fire, all enthusiasm, all meaning, all creative urge. That is the ultimate theme of the book – Howard Roark as the remedy for all modern ills.

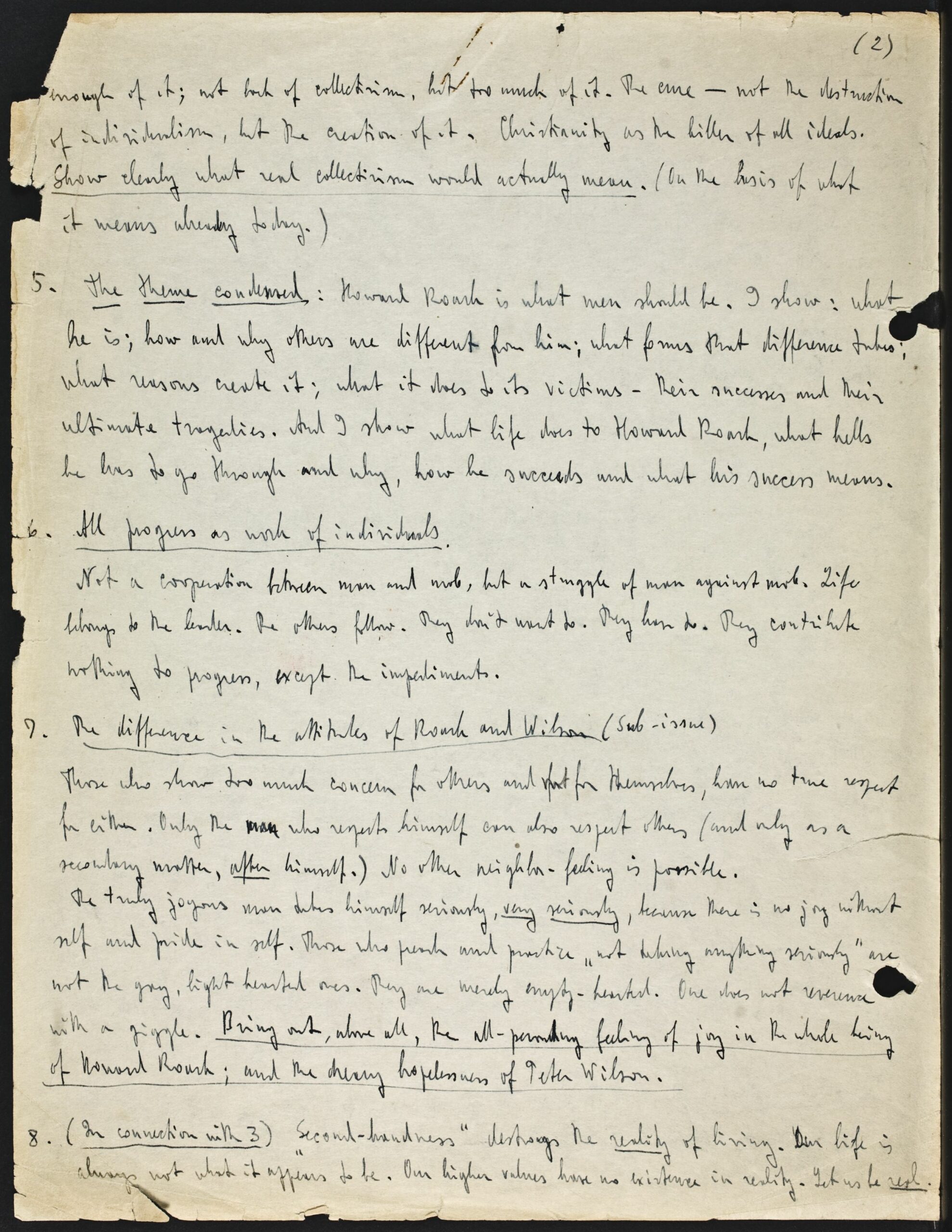

The theme, then, goes like this: Howard Roark is what men should be. I show: how and why others are different from him; what forms that

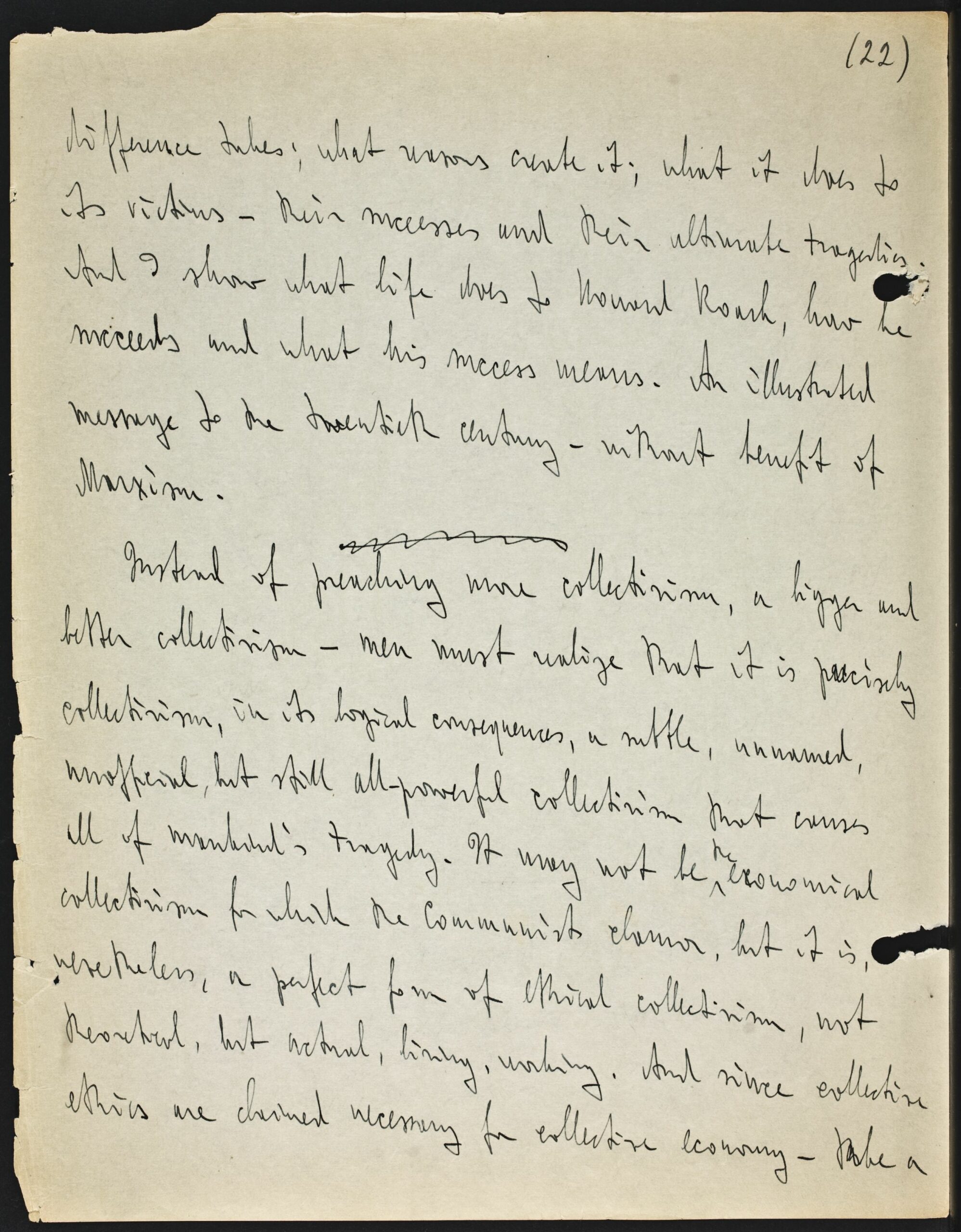

[Page 22]

(22)

difference takes; what reasons create it; what it does to its victims – their successes and their ultimate tragedies. And I show what life does to Howard Roark, how he succeeds and what his success means. An illustrated message to the twentieth century – without benefit of Marxism.

[canceled horizontal line]

Instead of preaching more collectivism, a bigger and better collectivism – men must realize that it is precisely collectivism, in its logical consequences, a subtle, unnamed, unofficial, but still all-powerful collectivism that causes all of mankind’s tragedy. It may not be the economical collectivism for which the Communists clamor, but it is, nevertheless, a perfect form of ethical collectivism, not theoretical, but actual, living, working. And since collective ethics are claimed necessary for collective economy – take a

[Page 23]

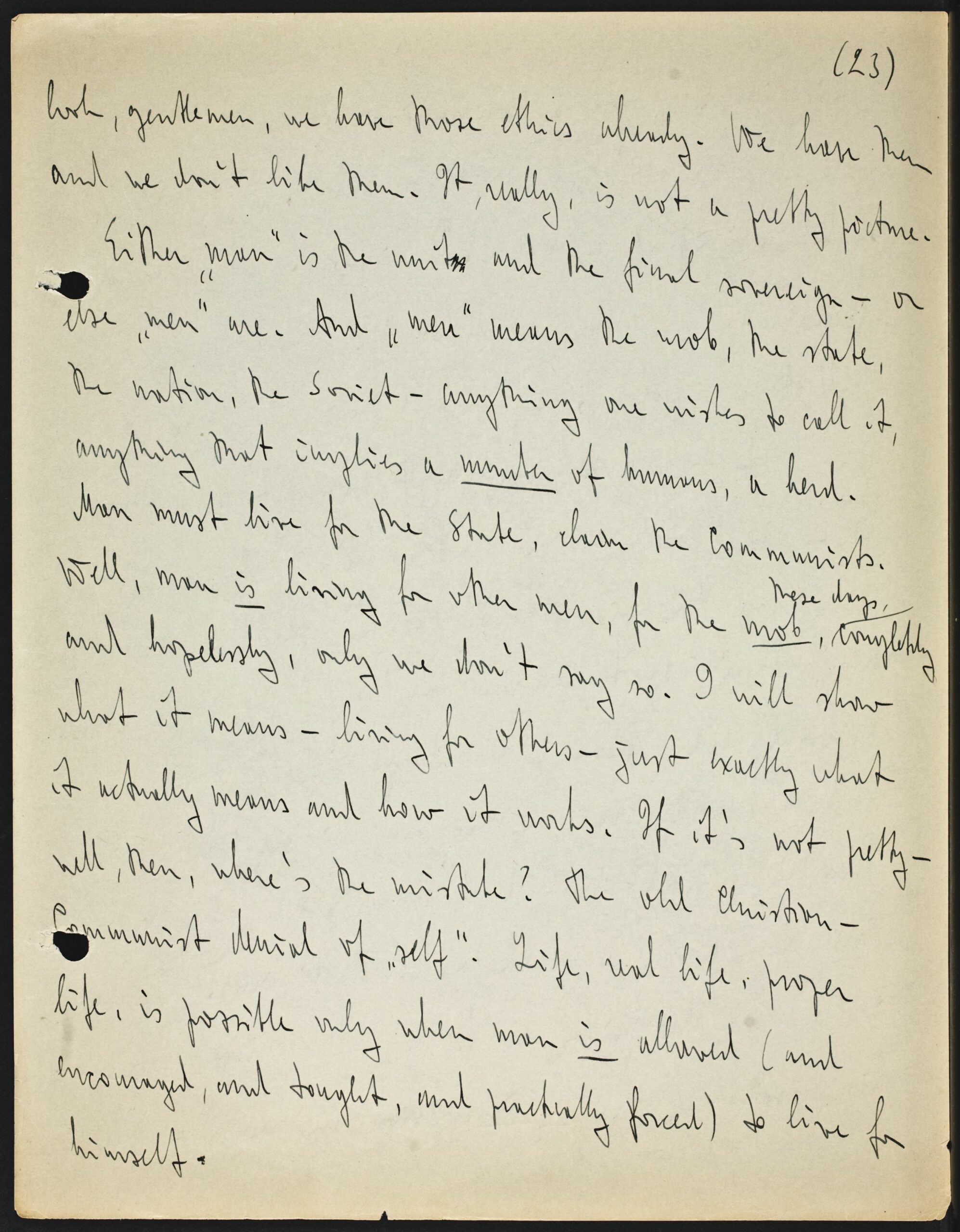

(23)

look, gentlemen, we have those ethics already. We have them and we don’t like them. It, really, is not a pretty picture.

Either “man” is the unite and the final sovereign – or else “men” are. And “men” means the mob, the state, the nation, the Soviet – anything one wishes to call it, anything that implies a number of humans, a herd. Man must live for the State, claim the Communists. Well, man is living for other men, for the mob, these days, completely and hopelessly, only we don’t say so. I will show what it means – living for others – just exactly what it actually means and how it works. If it’s not pretty – well, then, where’s the mistake? The old Christian-Communist denial of “self”. Life, real life, proper life, is possible only when man is allowed (and encouraged, and tought, and practically forced) to live for himself.

[Page 24]

(24)

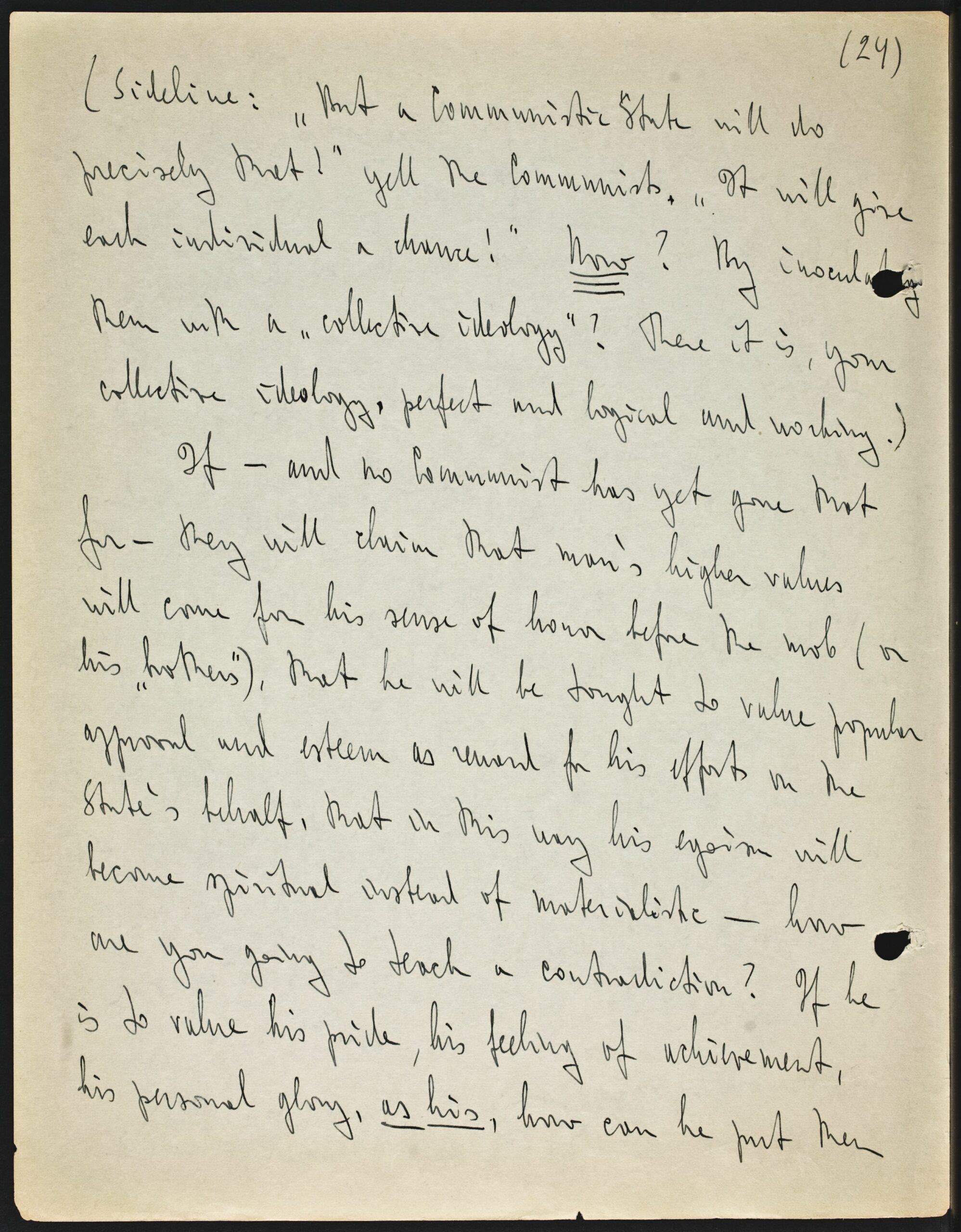

(Sideline: “But a Communistic State will do precisely that!” yell the Communists. “It will give each individual a chance!” How? By inoculating them with a “collective ideology”? There it is, your collective ideology, perfect and logical and working.)

If – and no Communist has yet gone that far – they will claim that man’s higher values will come from his sense of honor before the mob (or his “brothers”), that he will be tought to value popular approval and esteem as reward for his efforts on the State’s behalf, that in this way his egoism will become spiritual instead of materialistic – how are you going to teach a contradiction? If he is to value his pride, his feeling of achievement, his personal glory, as his, how can he put them

[Page 25]

(25)

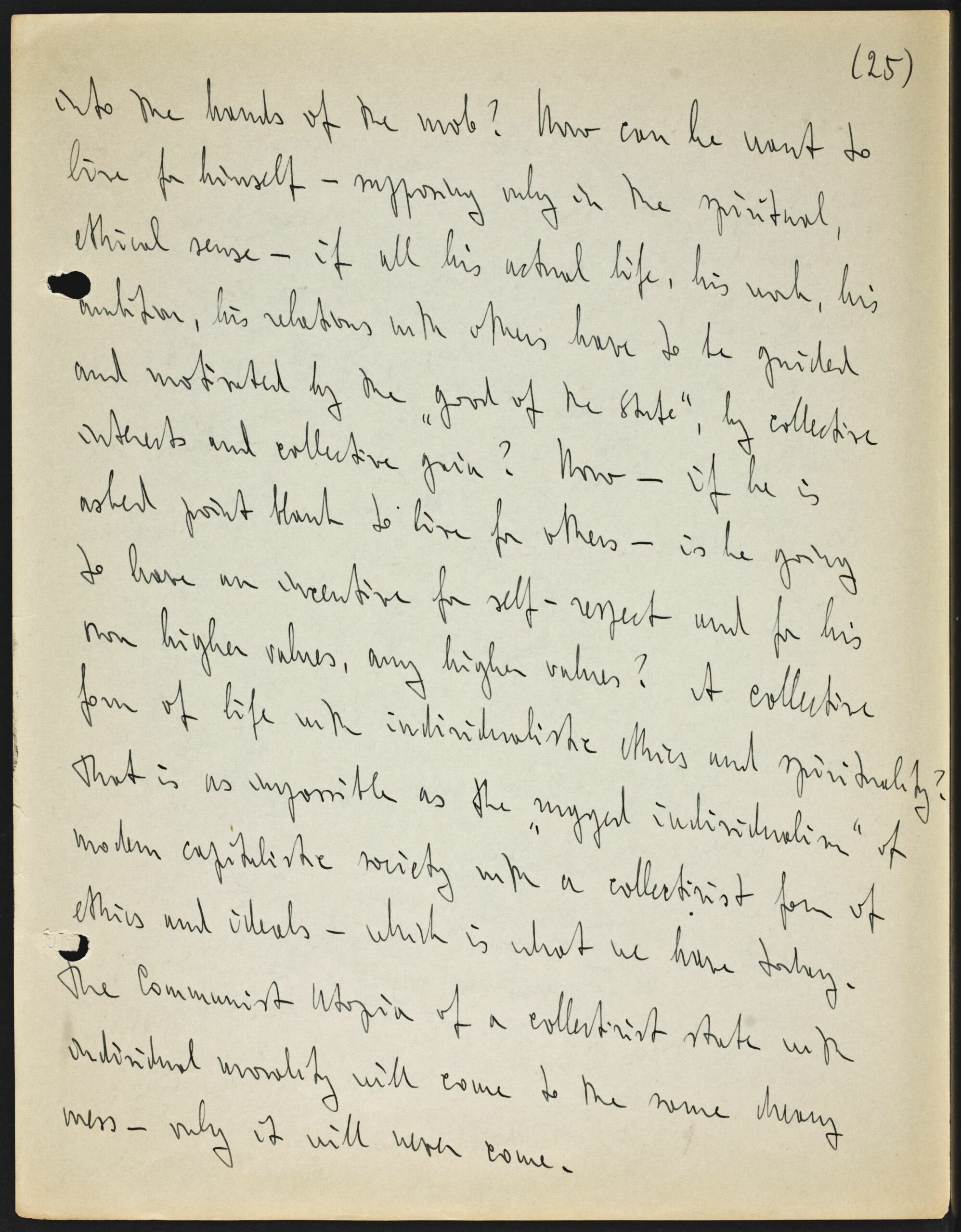

into the hands of the mob? How can he want to live for himself – supposing only in the spiritual, ethical sense – if all his actual life, his work, his ambition, his relations with others have to be guided and motivated by the “good of the State”, by collective interests and collective gain? How – if he is asked point blank to live for others – is he going to have an incentive for self-respect and for his own higher values, any higher values? A collective form of life with individualistic ethics and spirituality? That is as impossible as the “rugged individualism” of modern capitalistic society with a collectivist form of ethics and ideals – which is what we have today. The Communist Utopia of a collectivist state with individual morality will come to the same dreary mess – only it will never come.

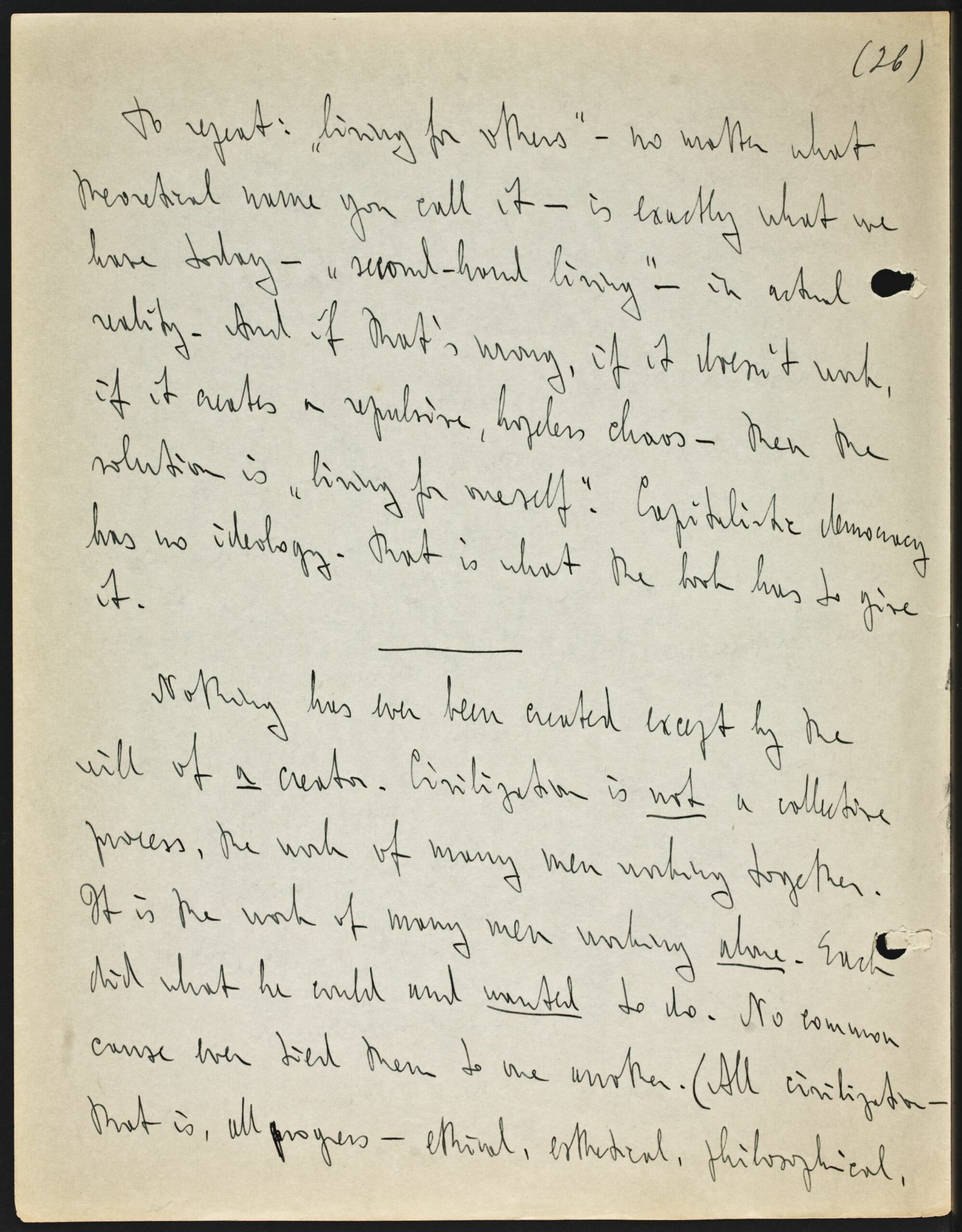

[Page 26]

(26)

To repeat: “living for others” – no matter what theoretical name you call it – is exactly what we have today – “second-hand living” – in actual reality. And if that’s wrong, if it doesn’t work, if it creates a repulsive, hopeless chaos – then the solution is “living for oneself”. Capitalistic democracy has no ideology. That is what the book has to give it.

Nothing has ever been created except by the will of a creator. Civilization is not a collective process, the work of many men working together. It is the work of many men working alone. Each did what he could and wanted to do. No common cause ever tied them to one another. (All civilization – that is, all progress – ethical, esthetical, philosophical,

[Page 27]

(27)

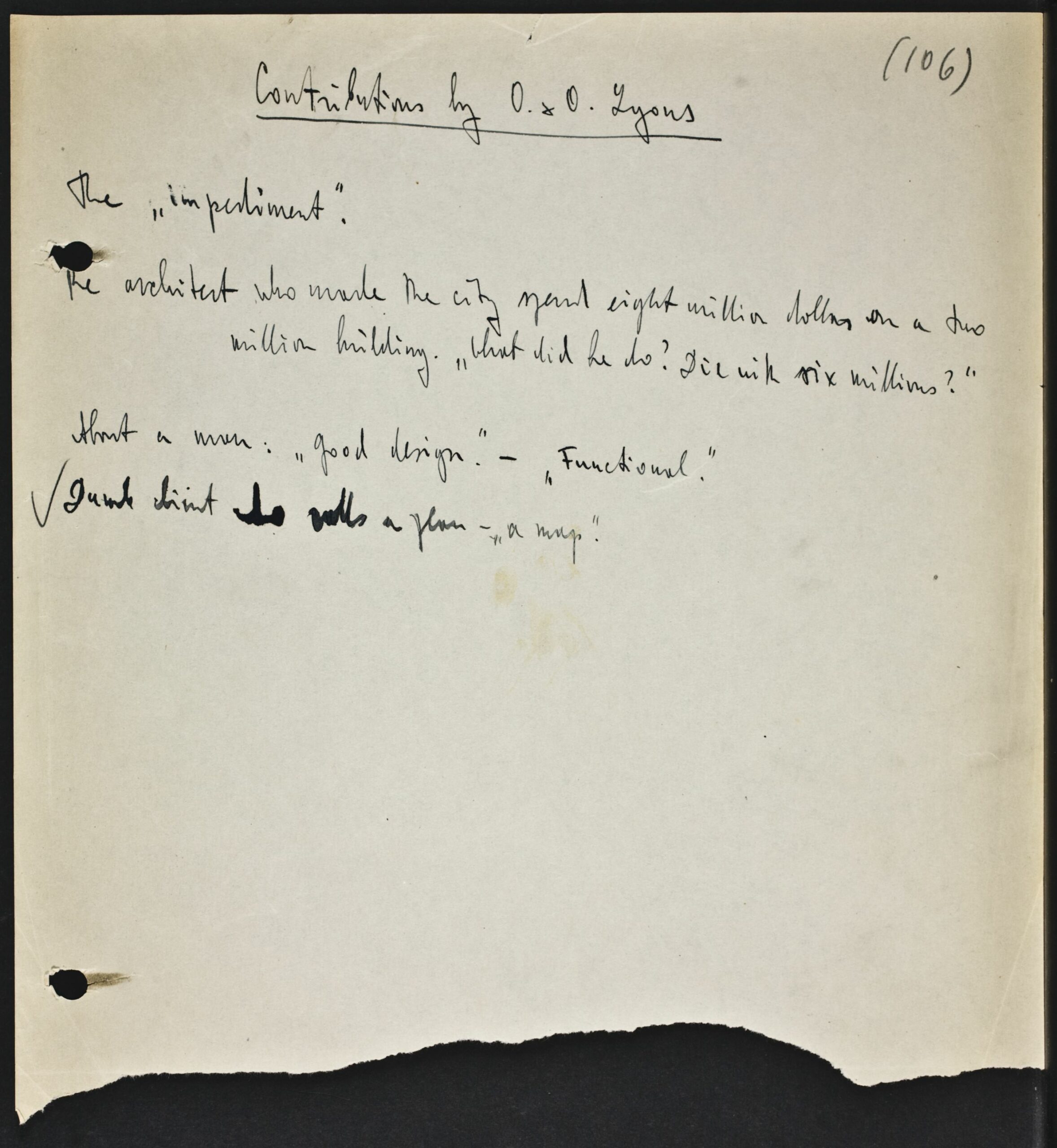

scientific – has been accomplished not by a cooperation between an originator and his followers, between man and the mob, but by a struggle between man and the mob. The mob has ever been against all novelty, all originality, everything new and forward moving. It is individual men who make the forward step, in each case, only to pay for it, often with their lives, because the mob resented it. But the world did move forward, because life belongs to the leaders and the exceptions. The others follow. They don’t want to. They have to. They contribute nothing to progress, except the impediments)

If the best part of life, the mental life, everything above mere material existence, is creation essentially, it presuposes a sense of valuation. How can

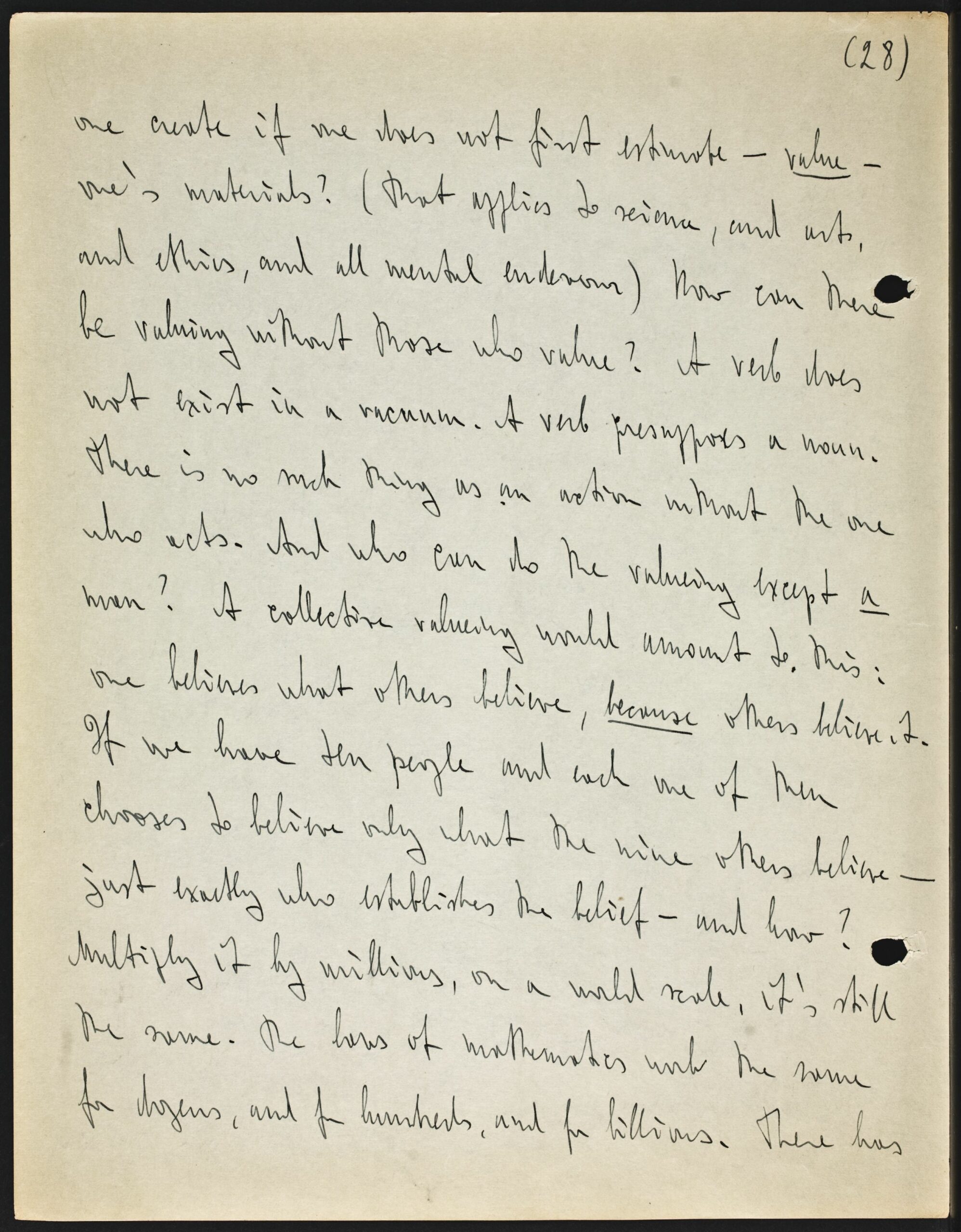

[Page 28]

(28)

one create if one does not first estimate – value – one’s materials? (That applies to science, and arts, and ethics, and all mental endevour) How can there be valuing without those who value? A verb does not exist in a vacuum. A verb presupposes a noun. There is no such thing as an action without the one who acts. And who can do the valueing except a man? A collective valueing would amount to this: one believes what others believe, because others believe it. If we have ten people and each one of them chooses to believe only what the nine others believe – just exactly who establishes the belief – and how? Multiply it by millions, on a world scale, it’s still the same. The laws of mathematics work the same for dozens, and for hundreds, and for billions. There has

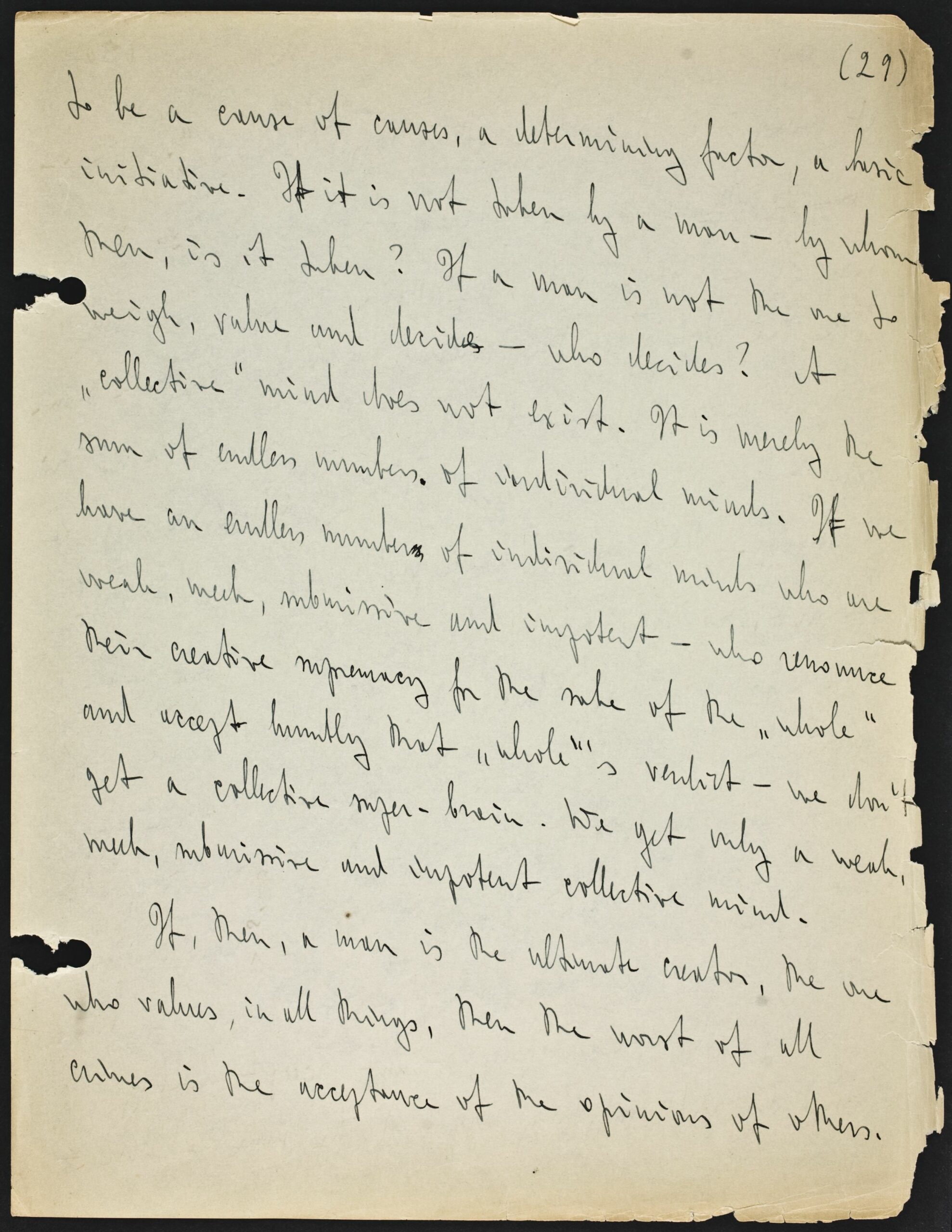

[Page 29]

(29)

to be a cause of causes, a determining factor, a basic initiative. If it is not taken by a man – by whom then, is it taken? If a man is not the one to weigh, value and decides – who decides? A “collective” mind does not exist. It is merely the sum of endless numbers. of individual minds. If we have an endless numbers of individual minds who are weak, meek, submissive and impotent – who renounce their creative supremacy for the sake of the “whole” and accept humbly that “whole”’s verdict – we don’t get a collective super-brain. We get only a weak, meek, submissive and impotent collective mind.

If, then, a man is the ultimate creator, the one who values, in all things, then the worst of all crimes is the acceptance of the opinions of others.

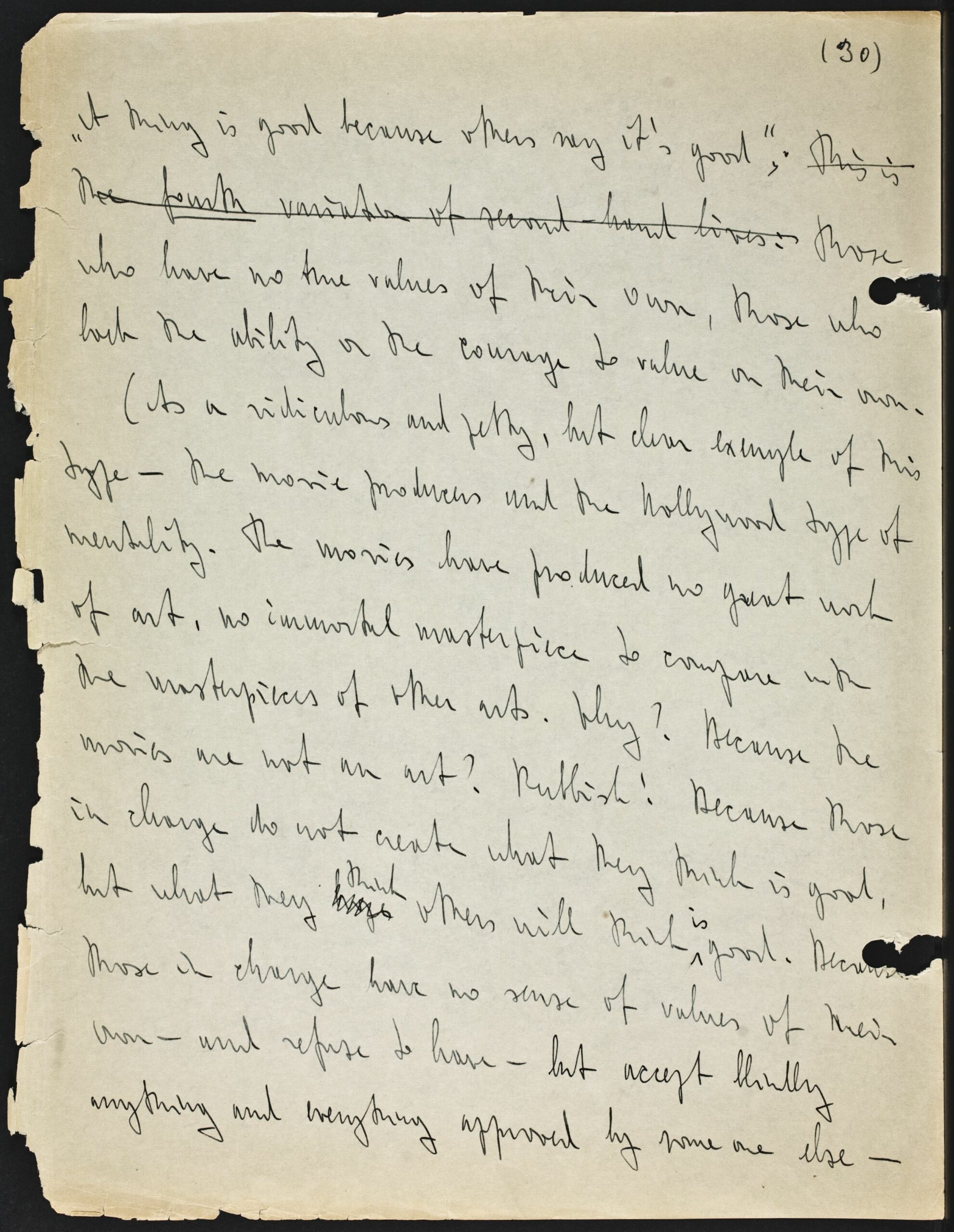

[Page 30]

(30)

“A thing is good because others say it’s good”; this is the fourth variation of second-hand lives: those who have no true values of their own, those who lack the ability or the courage to value on their own.

(As a ridiculous and petty, but clear example of this type – the movie producers and the Hollywood type of mentality. The movies have produced no great work of art, no immortal masterpiece to compare with the masterpieces of other arts. Why? Because the movies are not an art? Rubbish! Because those in charge do not create what they think is good, but what they hope think others will think is good. Because those in charge have no sense of values of their own – and refuse to have – but accept blindly anything and everything approved by some one else –

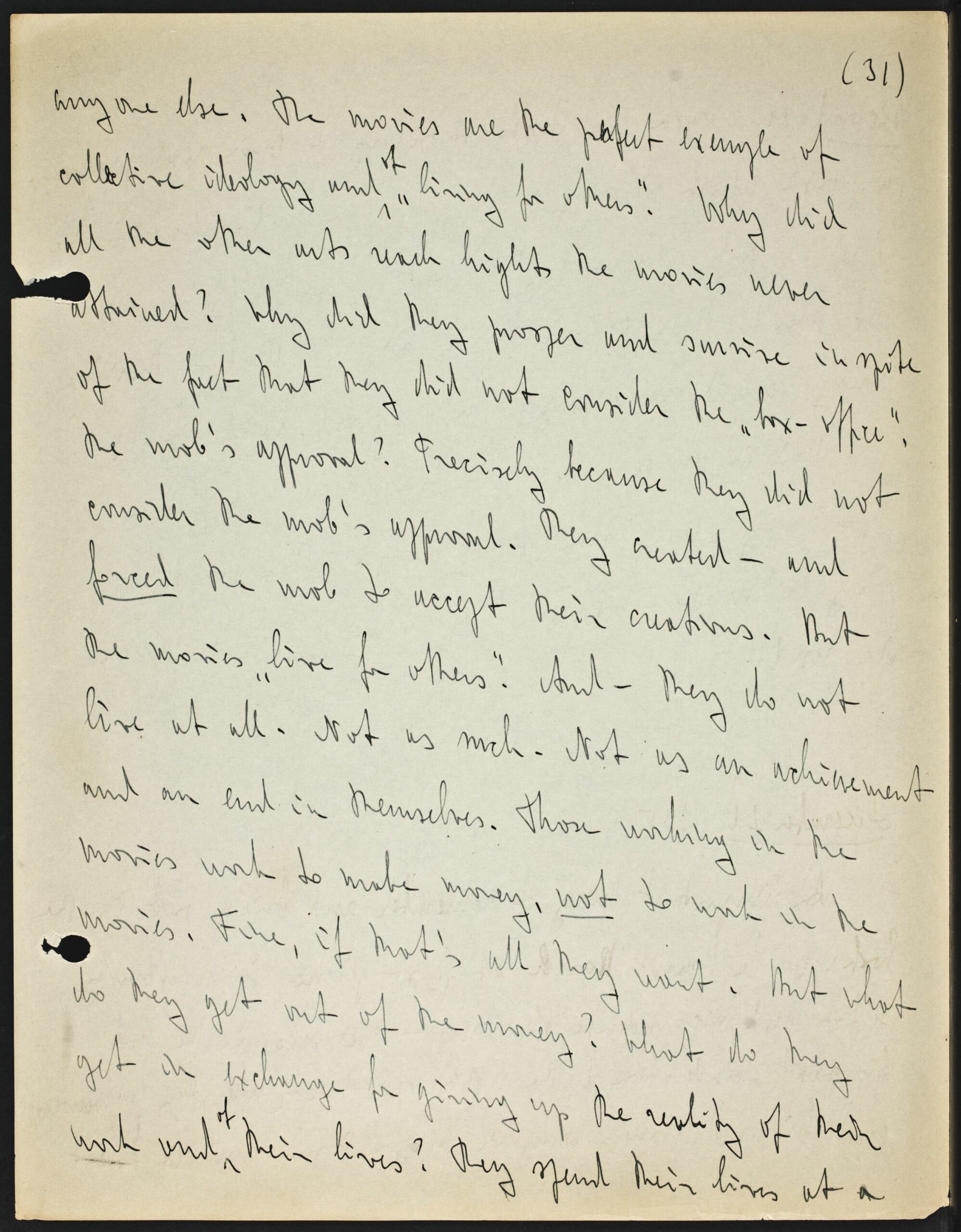

[Page 31]

(31)

anyone else. The movies are the perfect example of collective ideology and of “living for others”. Why did all the other arts reach heights the movies never attained? Why did they prosper and survive in spite of the fact that they did not consider the “box-office”, the mob’s approval? Precisely because they did not consider the mob’s approval. They created – and forced the mob to accept their creations. But the movies “live for others”. And – they do not live at all. Not as such. Not as an achievement and an end in themselves. Those working in the movies work to make money, not to work in the movies. Fine, if that’s all they want. But what do they get out of the money? What do they get in exchange for giving up the reality of their work and of their lives? They spend their lives at a

[Page 32]

(32)

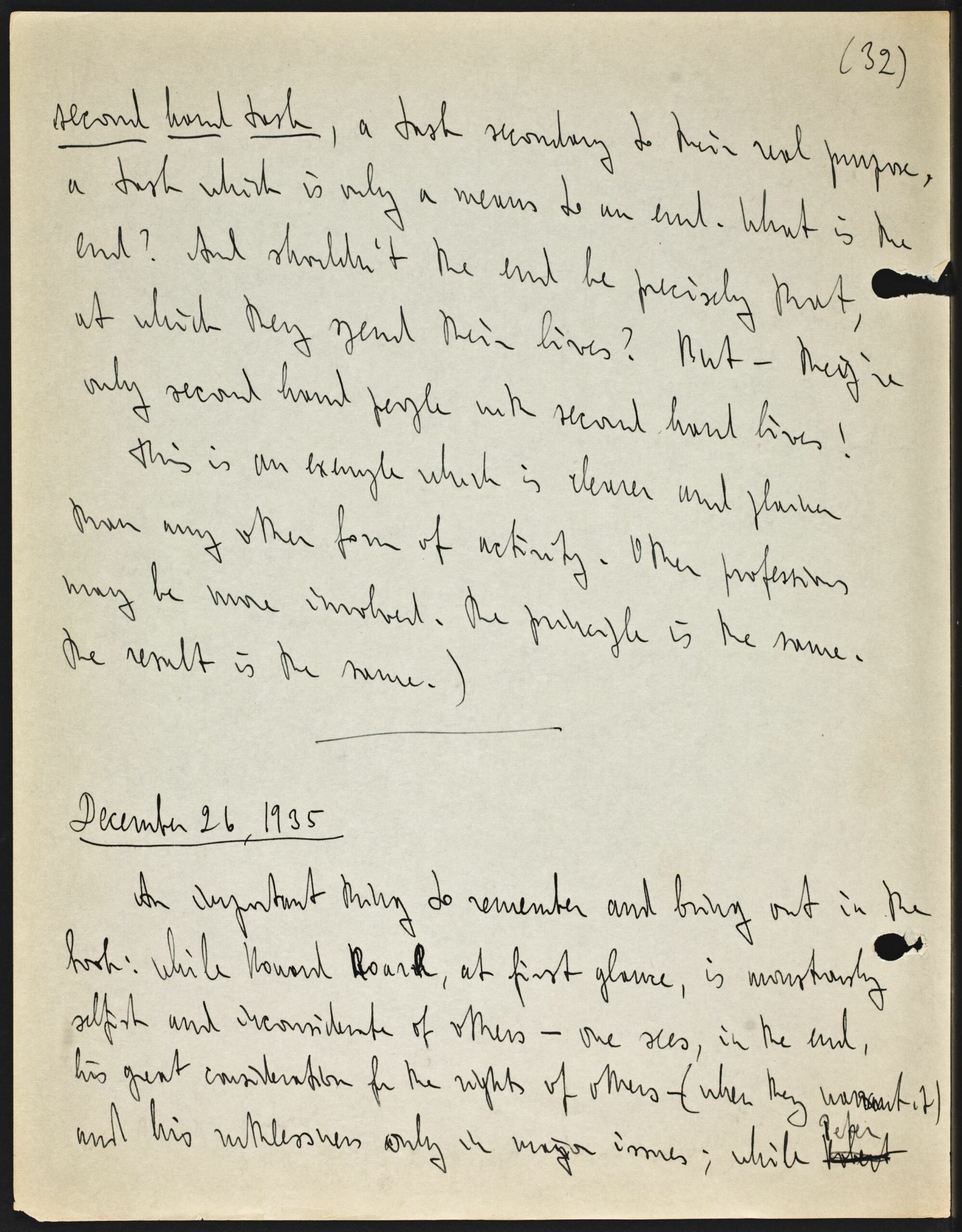

second hand task, a task secondary to their real purpose, a task which is only a means to an end. What is the end? And shouldn’t the end be precisely that, at which they spend their lives? But – they’re only second hand people with second hand lives!

This is an example which is clearer and plainer than any other form of activity. Other professions may be more involved. The principle is the same. The result is the same.)

December 26, 1935

An important thing to remember and bring out in the book: while Howard Roark, at first glance, is monstrously selfish and inconsiderate of others – one sees, in the end, his great consideration for the rights of others – (when they warrant it) and his ruthlessness only in major issues; while Robert Peter

[Page 33]

(33)

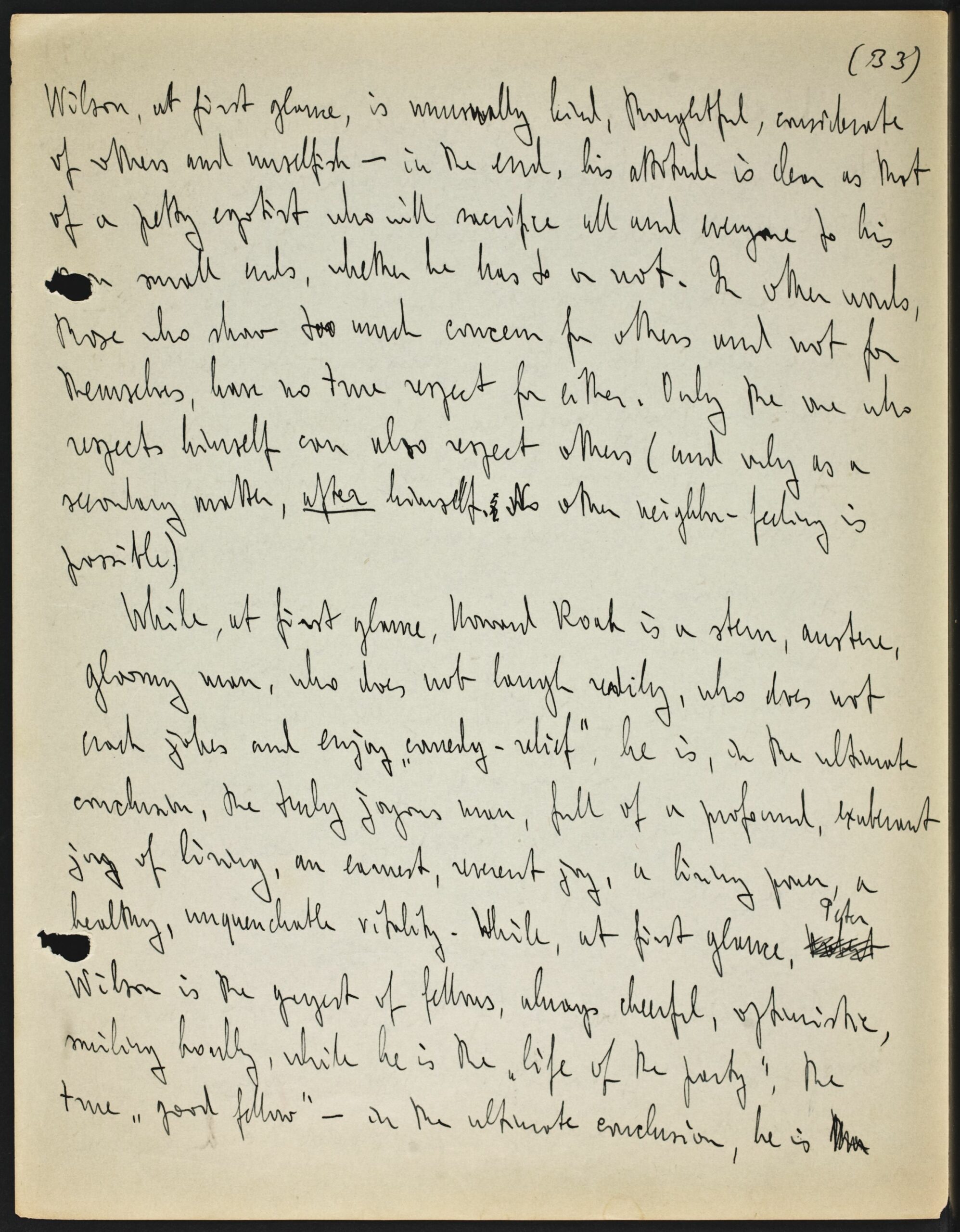

Wilson, at first glance, is unusually kind, thoughtful, considerate of others and unselfish – in the end, his attitude is clear as that of a petty egotist who will sacrifice all and everyone to his [?own] small ends, whether he has to or not. In other words, those who show too much concern for others and not for themselves, have no true respect for either. Only the one who respects himself can also respect others (and only as a secondary matter, after himself. No other neighbor-feeling is possible.)

While, at first glance, Howard Roark is a stern, austere, gloomy man, who does not laugh readily, who does not crack jokes and enjoy “comedy-relief”, he is, in the ultimate conclusion, the truly joyous man, full of a profound, exuberant joy of living, an earnest, reverent joy, a living power, a healthy, unquenchable vitality. While, at first glance, Robert Peter Wilson is the gayest of fellows, always cheerful, optimistic, smiling broadly, while he is the “life of the party”, the true “good fellow” – in the ultimate conclusion, he is the

[Page 34]

(34)

a sad, desolate man, empty, desperate in his emptiness, without life, without joy, hope or aim, a bitter cynic hiding his cynical despair under a superficial, forced gaiety.

The truly joyous man does not laugh too much – because there is very little to laugh at in life as it is today. The truly joyous man takes himself seriously, very seriously, because there is no joy without self and pride in self. Those who preach and practice “not taking anything seriously” are not the gay, light-hearted ones. They are merely the empty-hearted. “Taking seriously” is the very essence of life. If one does not “take oneself seriously” one can take nothing seriously. And – “the noble soul has reverence for itself.” One does not reverence with a giggle.

Bring out – above all – the subtle, all-pervading, inescapable feeling of joy, of joyous energy that permeates the whole being of Howard Roark and his

[Page 35]

(35)

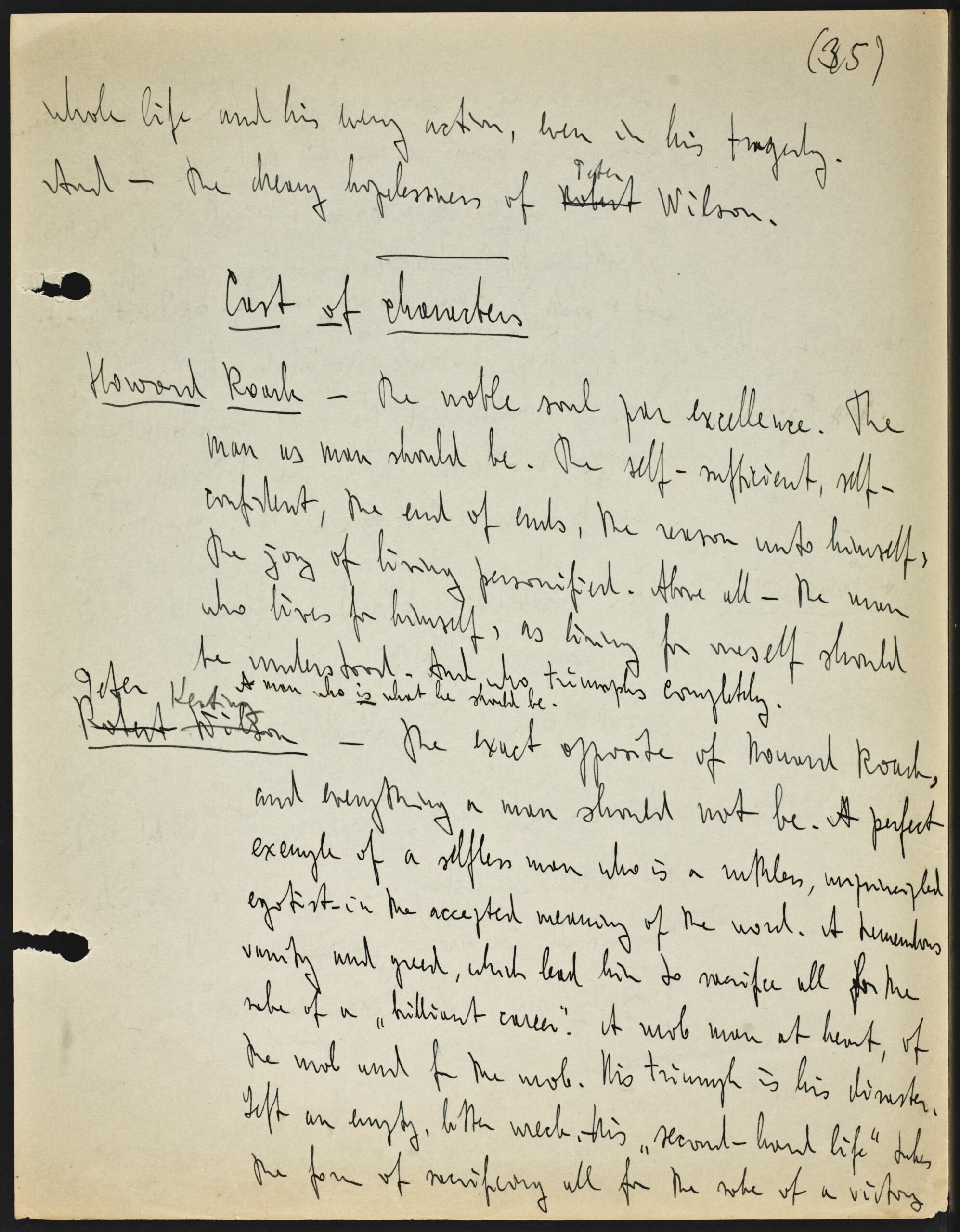

whole life and his every action, even in his tragedy. And – the dreary hopelessness of Robert Peter Wilson.

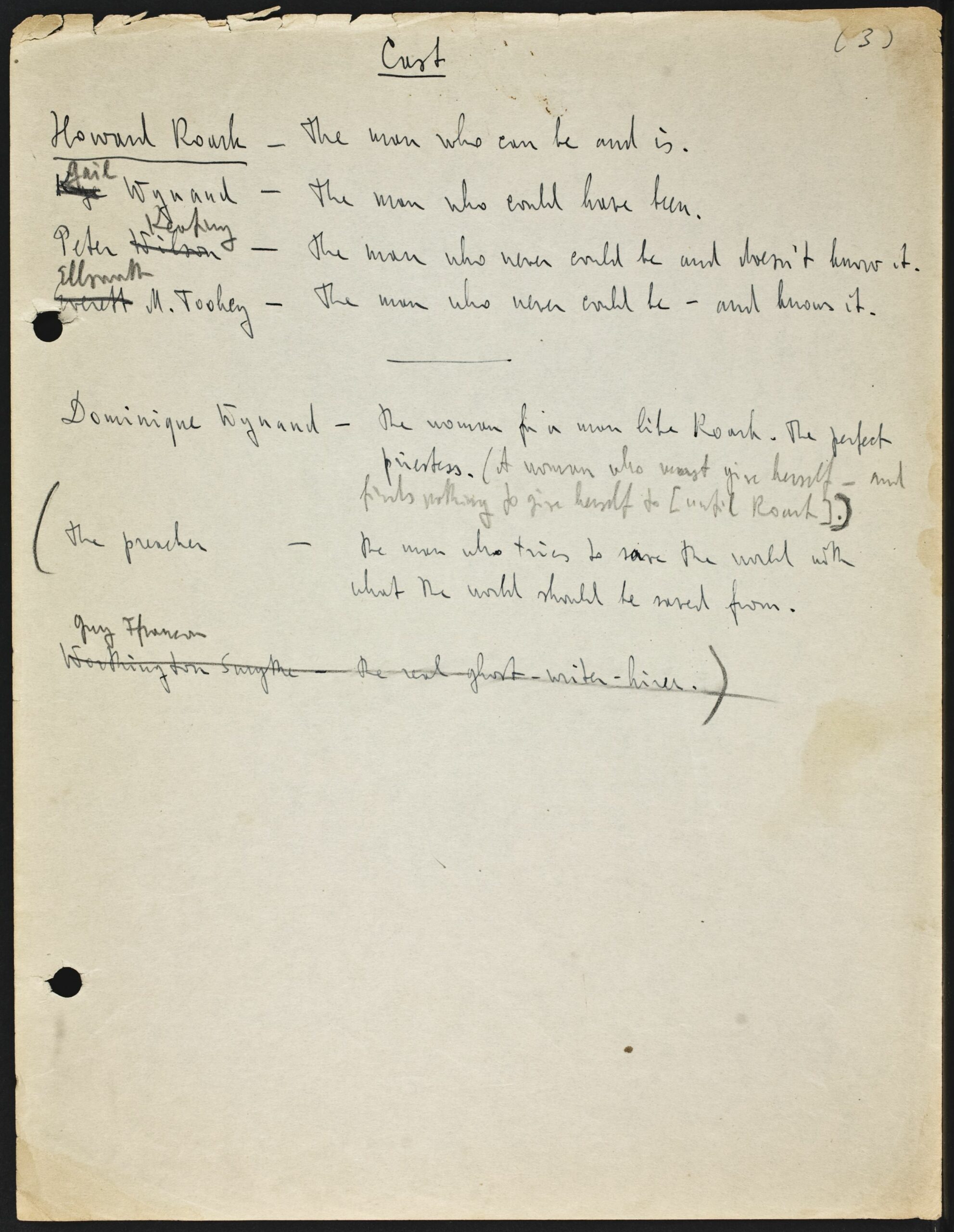

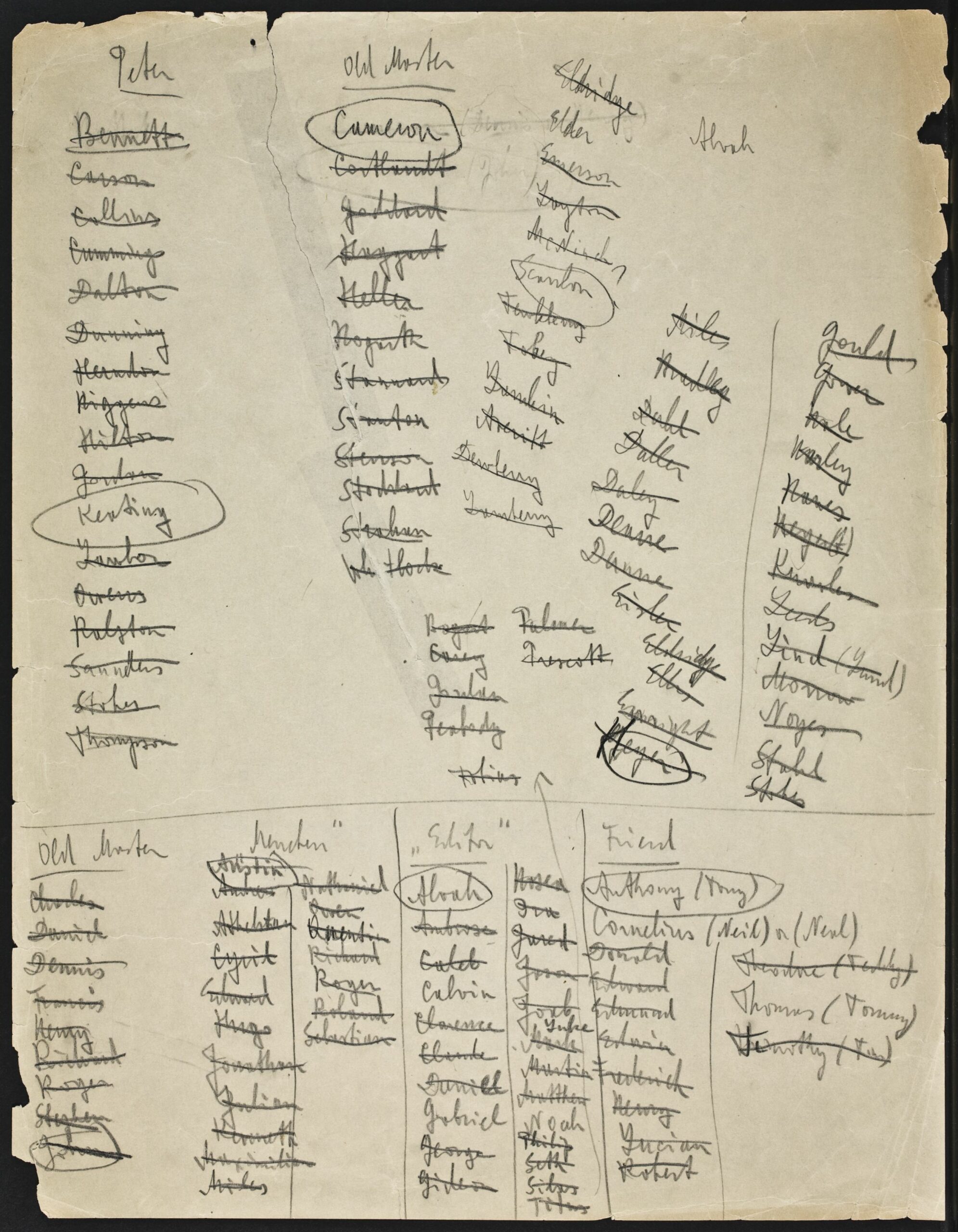

Cast of characters

Howard Roark – the noble soul par excellence. The man as man should be. The self-sufficient, self-confident, the end of ends, the reason unto himself, the joy of living personified. Above all – the man who lives for himself, as living for oneself should be understood. And who triumphs completely. A man who is what he should be.

Robert Wilson Peter Keating – the exact opposite of Howard Roark, and everything a man should not be. A perfect example of a selfless man who is a ruthless, unprincipled egotist – in the accepted meaning of the word. A tremendous vanity and greed, which lead him to sacrifice all for the sake of a “brilliant career”. A mob man at heart, of the mob and for the mob. His triumph is his disaster. Left an empty, bitter wreck,–his“second-hand life” takes the form of sacrificing all for the sake of a victory

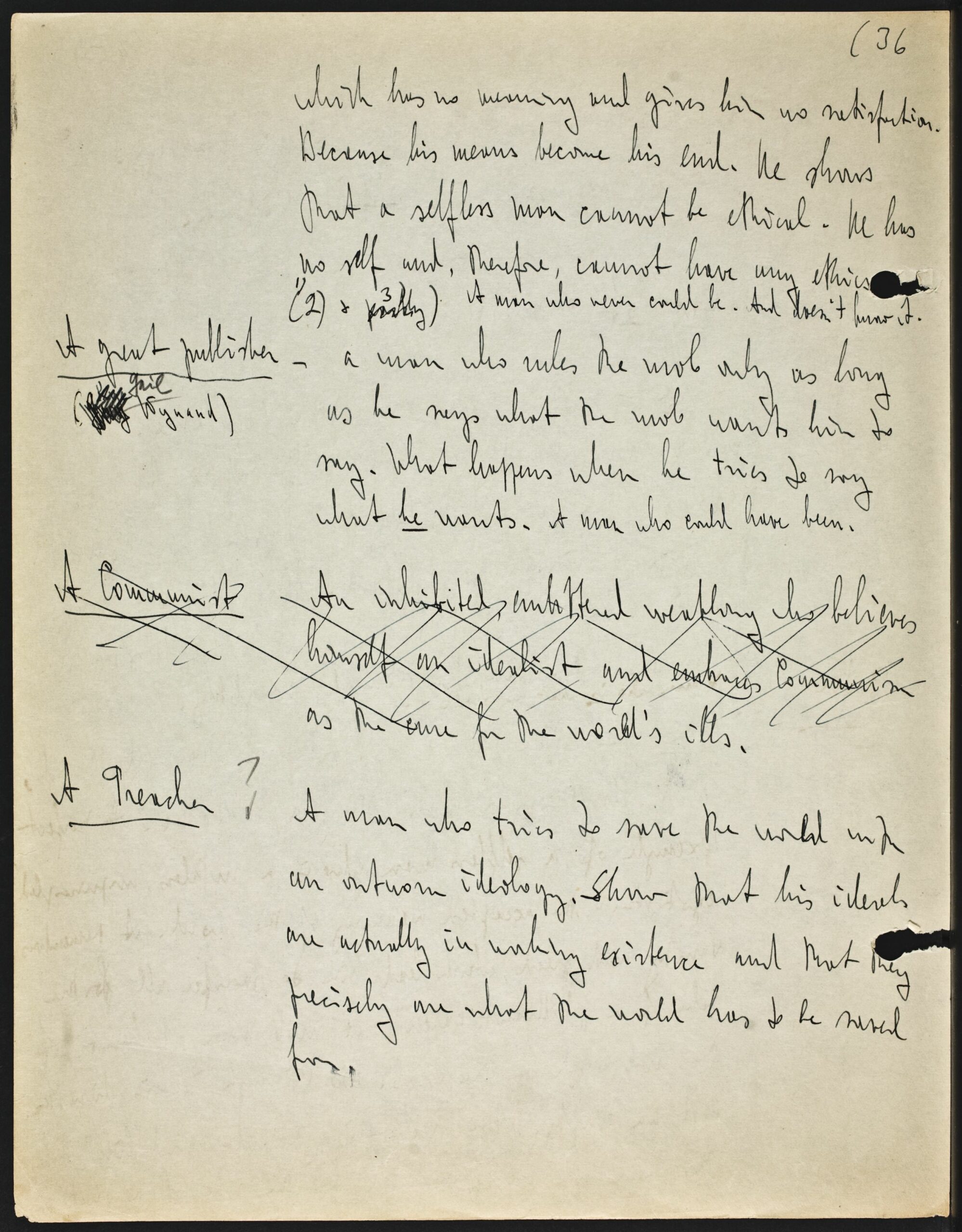

[Page 36]

(36

which has no meaning and gives him no satisfaction. Because his means become his end. He shows that a selfless man cannot be ethical. He has no self and, therefore, cannot have any ethics. 1) (2) + partly 3)) A man who never could be. And doesn’t know it.

A great publisher ([?Guy][?Gay][?Kye] Gail Wynand) – a man who rules the mob only as long as he says what the mob wants him to say. What happens when he tries to say what he wants. A man who could have been.

A Communist An inhibited, embittered weakling who believes himself an idealist and embraces Communism as the cure for the world’s ills.

A Preacher ? A man who tries to save the world with an outworn ideology. Show that his ideals are actually in waking existence and that they precisely are what the world has to be saved from.

[Page 37]

(37)

An art producer (Stage or (Screen) A man who has no opinions and no values, save those of others.

The actress (Lona) Vesta Dunning A woman who accepts greatness in other people’s eyes, rather than in her own (3) A woman who could have been.

Dominique Wynand The woman for a man like Howard Roark. The perfect priestess.

J. Worthington Smythe John Eric Snyte The real ghost-writer-hirer. A man who glories in appropriating the achievements of others.

Ellsworth Everett Monkton Toohey [illegible][?Huls][?Flent] Toohey – Noted economist, critic and liberal. “Noted” anything and everything. Great “humanitarian” and “man of integrity”. Glorifies all forms of collectivism because he knows that only under such forms will he, as the best representative of the mass, attain prominence and distinction, impossible to him on his own merits which do not exist. The idol-crusher par excellence. Born, organic enemy of all things heroic. Has a positive genius for the commonplace. Worst of all possible rats. [?Am] A man who never could be – and knows it.

[Page 38]

(38)

[page otherwise blank, crossed out]

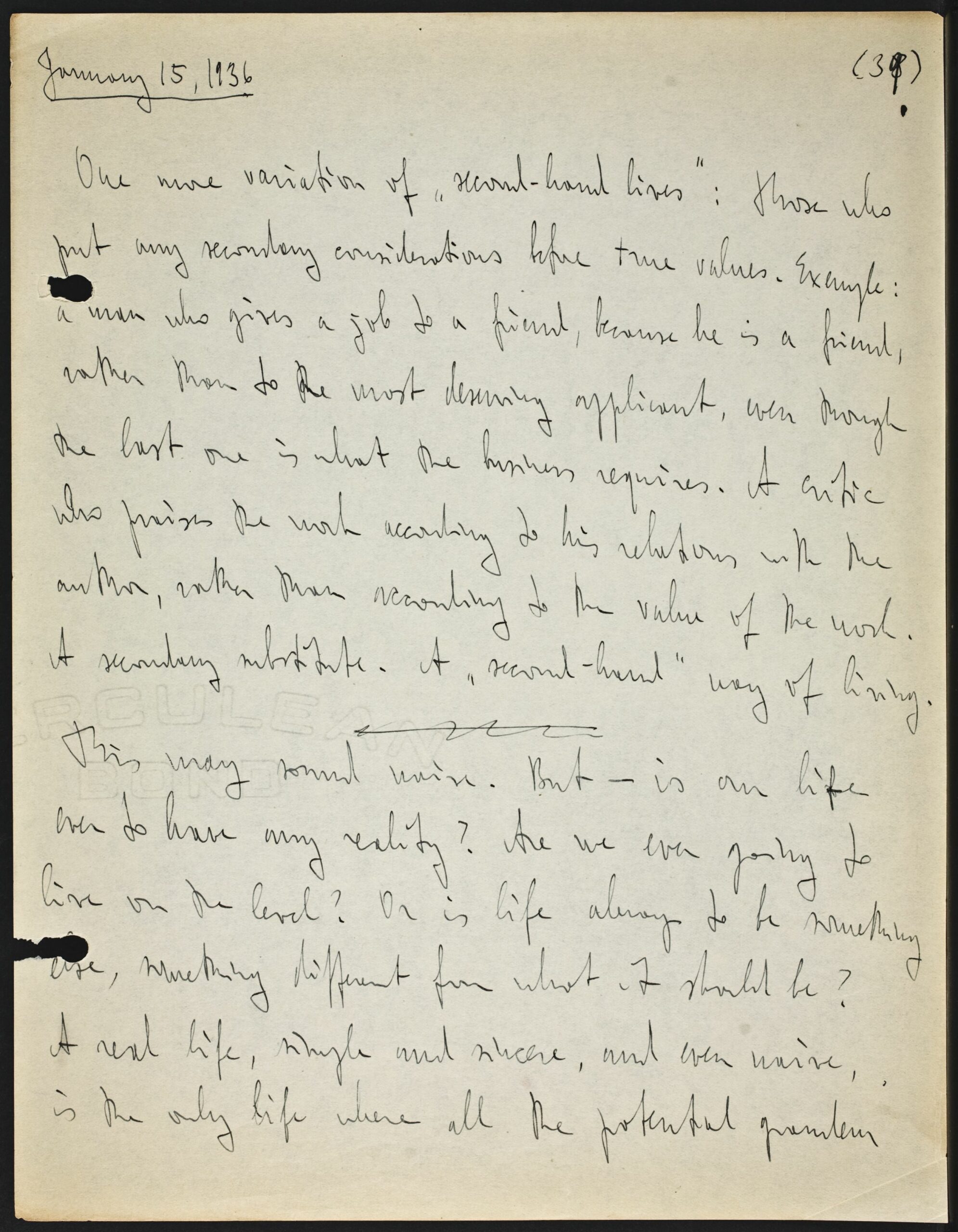

[Page 39]

(389)

January 15, 1936

One more variation of “second-hand lives”: those who put any secondary considerations before true values. Example: a man who gives a job to a friend, because he is a friend, rather than to the most deserving applicant, even though the last one is what the business requires. A critic who praises the work according to his relations with the author, rather than according to the value of the work. A secondary substitute. A “second-hand” way of living.

[canceled horizontal line]

This may sound naive. But – is our life ever to have any reality? Are we ever going to live on the level? Or is life always to be something else, something different from what it should be? A real life, simple and sincere, and even naive, is the only life where all the potential grandeur

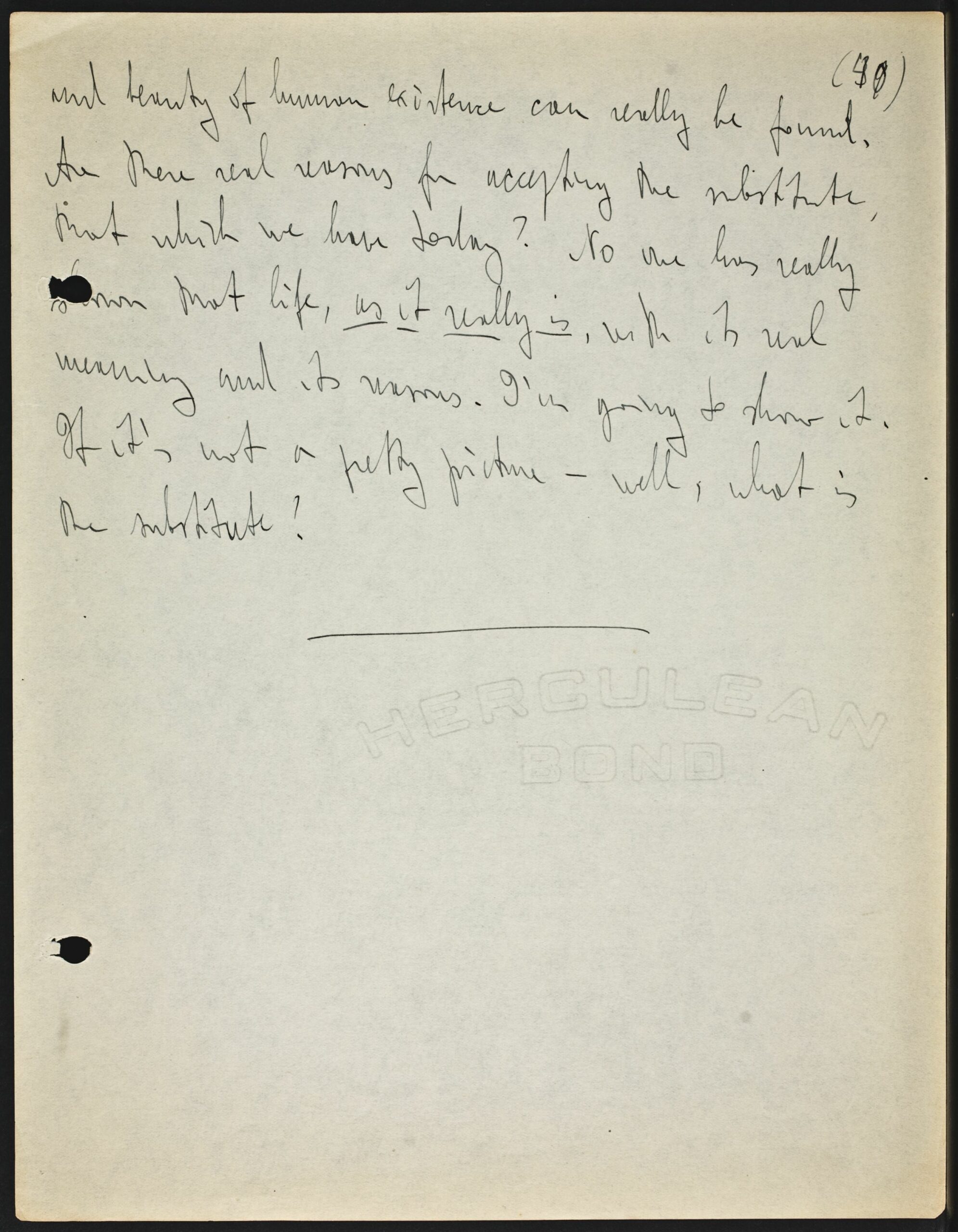

[Page 40]

(3940)

and beauty of human existence can really be found. Are there real reasons for accepting the substitute, that which we have today? No one has really [?shown] that life, as it really is, with its real meaning and its reasons. I’m going to show it. If it’s not a pretty picture – well, what is the substitute?

[Page 41]

(401)

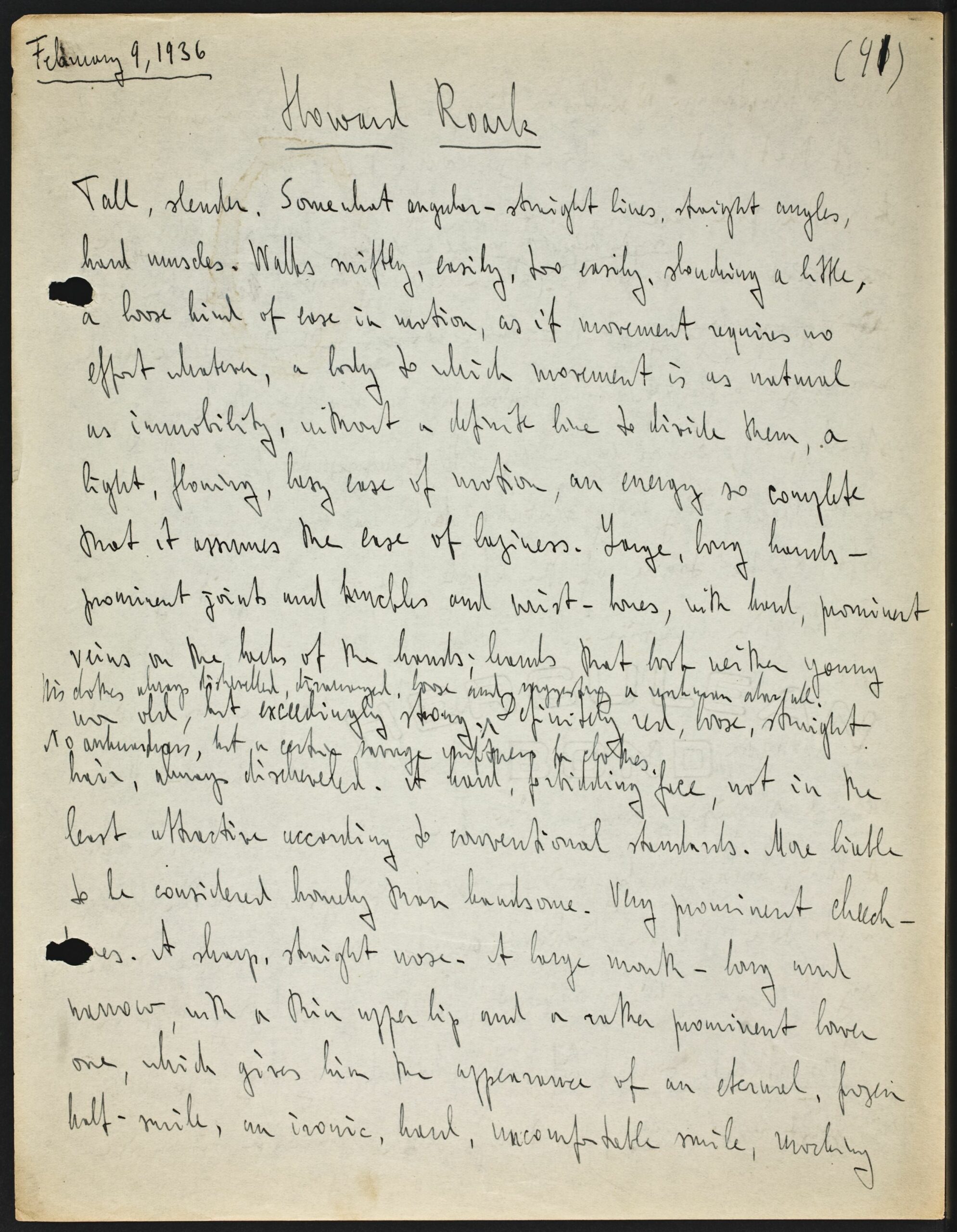

February 9, 1936

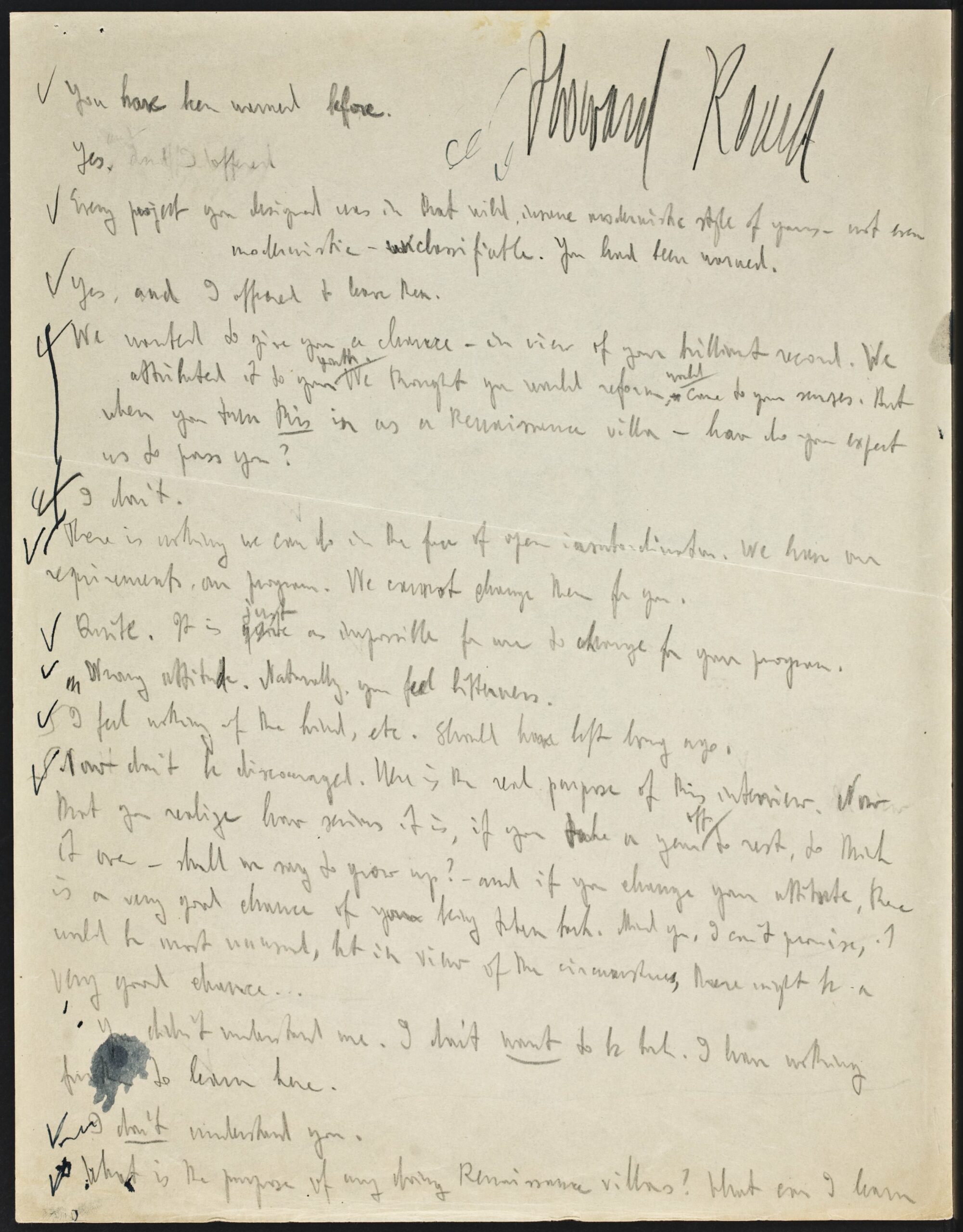

Howard Roark

Tall, slender. Somewhat angular – straight lines, straight angles, hard muscles. Walks swiftly, easily, too easily, slouching a little, a loose kind of ease in motion, as if movement requires no effort whatever, a body to which movement is as natural as immobility, without a definite line to divide them, a light, flowing, busy ease of motion, an energy so complete that it assumes the ease of laziness. Large, long hands – prominent joints and knuckles and wrist-bones, with hard, prominent veins on the backs of the hands; hands that look neither young nor old, but exceedingly strong. His clothes always disheveled, disarranged, loose and suggesting a [?workman] above all. No awkwardness, but a certain savage [?unfitness] for clothes. Definitely red, loose, straight hair, always discheveled. A hard, forbidding face, not in the least attractive according to conventional standards. More liable to be considered homely than handsome. Very prominent cheek-[?bones]. A sharp, straight nose. A large mouth – long and narrow, with a thin upper lip and a rather prominent lower one, which gives him the appearance of an eternal, frozen half-smile, an ironic, hard, uncomfortable smile, mocking

[Page 42]

(42) (41)

and contemptuous. Wrinkles or dimples or slightly prominent muscles, all of that and [?more] definitely, around the corners of his mouth. A rather pale face, without color on the cheeks, and with an abundance of freckles. over the bridge of the nose and the cheekbones. Dark red eyebrows,[?thin] not too heavy and thin and straight [?raising] up slightly at the outer corners, with the same hard, mocking, mephistolean expression as the mouth. Dark gray, steady, expressionless eyes – eyes that refuse to show expression, to be exact. Very long, straight, dark red eyelashes – the only soft, gentle touch of the whole face – a surprising touch in his grim expression. And when he laughs – which happens seldom – his mouth opens wide, with a complete, loose kind of abandon, and dimples appear on his sunken cheeks – the second surprising touch on his face – young, childish dimples. (?) A low, hard, throaty voice – not rasping, but rather blurred in its tone, though distinct in its sounds, with the same soft, busy fluency as his movements, neither one being soft or lazy.

His attitude toward life. Has learned very long ago, with his first consciousness, two things which dominate his entire

[Page 43]

(43)

attitude toward life: his own superiority and the utter worthlessness of the world. He knows what he wants and what he thinks. He needs no other reasons, standards or [?considerations]. His complete selfishness is as natural to him as breathing. He did not acquire it. He did not come to it through any logical deductions. He was born with it. He never questions it because even the possibility of questioning it never occurs to him. It is an axiom to him as much as the fact of his being alive is an axiom. He is a man born with the perfect consciousness of a man. He is not even militant or defiant about his utter selfishness. No more than he could be defiant about the right to breathe and eat. He has the quiet, complete, irrevocable calm of an iron conviction. No dramatics, no hysteria, no sensitiveness about it – because there are no doubts. A quiet, almost indifferent acceptance of an irrevocable fact.

A quick, sharp mind, courageous and not afraid to be hurt, has long since grasped and understood completely that

[Page 44]

(44)

the world is not what he is and just exactly what that world is. Consequently, he can no longer be hurt. The world has no painful surprise for him, since he has accepted long ago just what he is to expect from the world. Indifference and an infinite, calm contempt is all he feels for the world and for other men, the men who are not like him. No “Prince-Flower” quality here, because he understands men thoroughly. And, understanding them, dismisses the whole subject. He knows what he wants and he knows the work he wants. That is all he expects of life. Being thoroughly a “reason unto himself” he does not long for others of his kind, for companionship and understanding. He also knows that the world will not give him the right to his work easily. He does not expect it to be given. He enters life prepared to find it a struggle. And being a warrior above all, he does not even consider himself a warrior. The state of strife and battle is natural to him as a synonym of life. He does not think of himself as “Howard Roark,’ a soldier”.

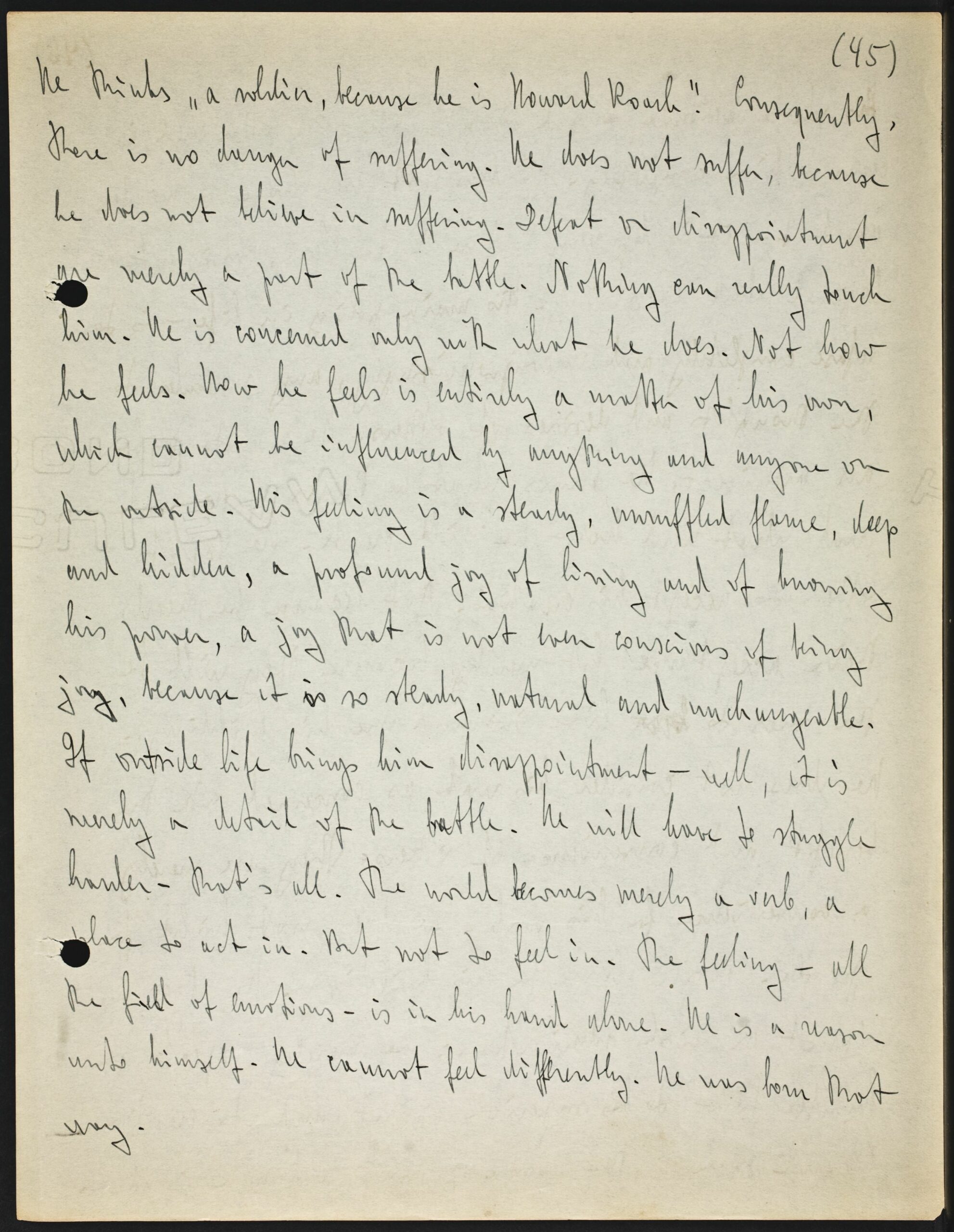

[Page 45]

(45)

He thinks “a soldier, because he is Howard Roark”. Consequently, there is no danger of suffering. He does not suffer, because he does not believe in suffering. Defeat or disappointment are merely a part of the battle. Nothing can really touch him. He is concerned only with what he does. Not how he feels. How he feels is entirely a matter of his own, which cannot be influenced by anything and anyone on the outside. His feeling is a steady, unruffled flame, deep and hidden, a profound joy of living and of knowing his power, a joy that is not even conscious of being joy, because it is so steady, natural and unchangeable. If outside life brings him disappointment – well, it is merely a detail of the battle. He will have to struggle harder – that’s all. The world becomes merely a verb, a place to act in. But not to feel in. The feeling – all the field of emotions – is in his hand alone. He is a reason unto himself. He cannot feel differently. He was born that way.

[Page 46]

(46)

His whole attitude toward himself, life and other men is clear to him completely. He does not even have to ponder about it – it is his very nature to be clear, consistent and logical about everything. His main policy in life – is to refuse, completely and uncompromisingly, any surrender to the thoughts and desires of others. He wants to be an architect. He knows what he thinks of his work and what and how he will create. He expects others to accept his creation. Not because he needs their acceptance, but merely because they will be the ones to [?liwe] live in and use his buildings. He does not consider his work as concerned with the benefit and convenience of others. They are merely a convenience for his work. He does not build for people. People live for his buildings. He does not expect or wish admiration: he merely expects an humble bow to his superior spirit and its creation – because such is the nature of things and mere justice.

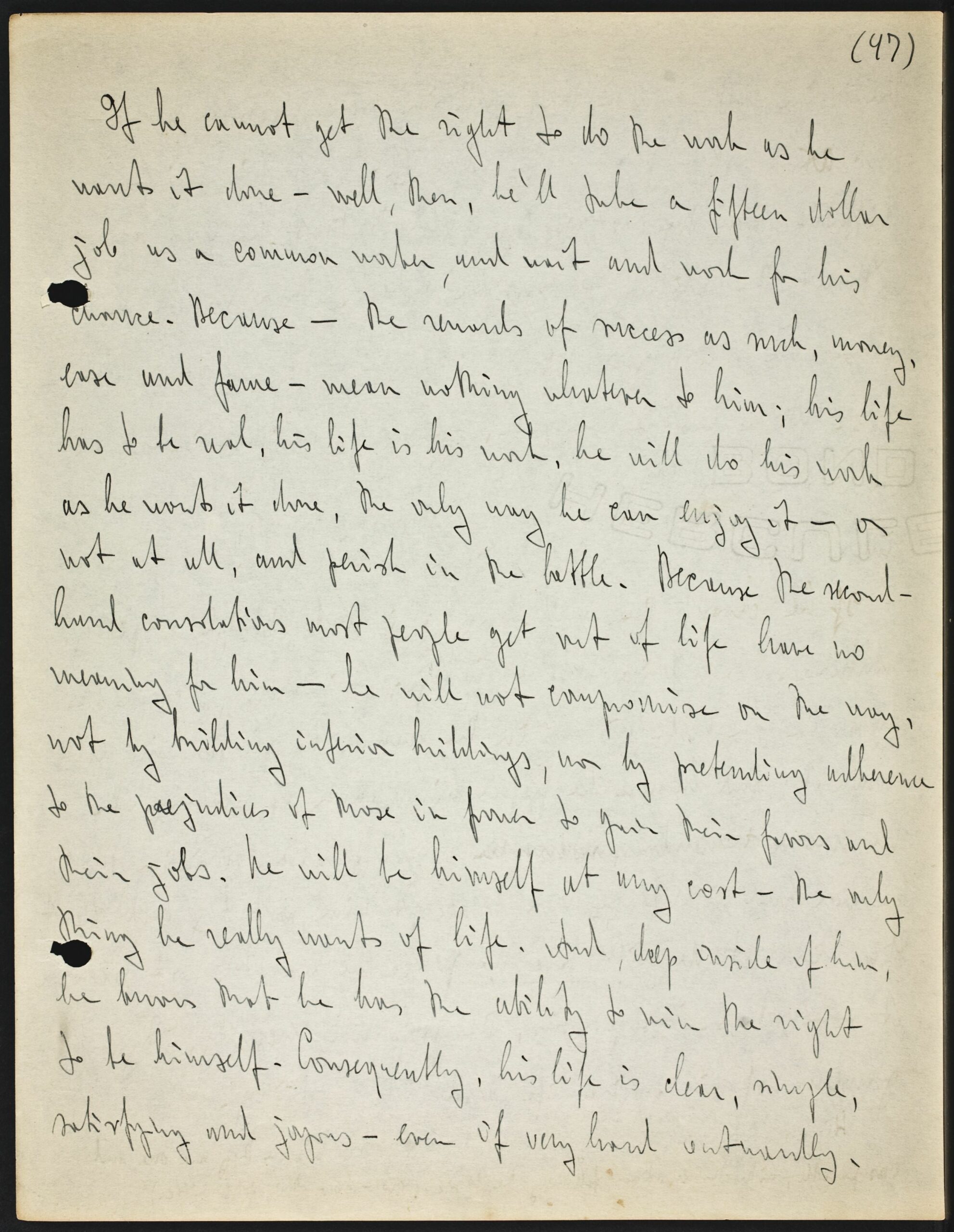

[Page 47]

(47)

If he cannot get the right to do the work as he wants it done – well, then, he’ll take a fifteen dollar job as a common worker, and wait and work for his chance. Because – the rewards of success as such, money, ease and fame – mean nothing whatever to him; his life has to be real, his life is his work, he will do his work as he wants it done, the only way he can enjoy it – or not at all, and perish in the battle. Because the second-hand consolations most people get out of life have no meaning for him – he will not compromise on the way, not by building inferior buildings, nor by pretending adherence to the prejudices of those in power to gain their favors and their jobs. He will be himself at any cost – the only thing he really wants of life. And, deep inside of him, he knows that he has the ability to win the right to be himself. Consequently, his life is clear, simple, satisfying and joyous – even if very hard outwardly.

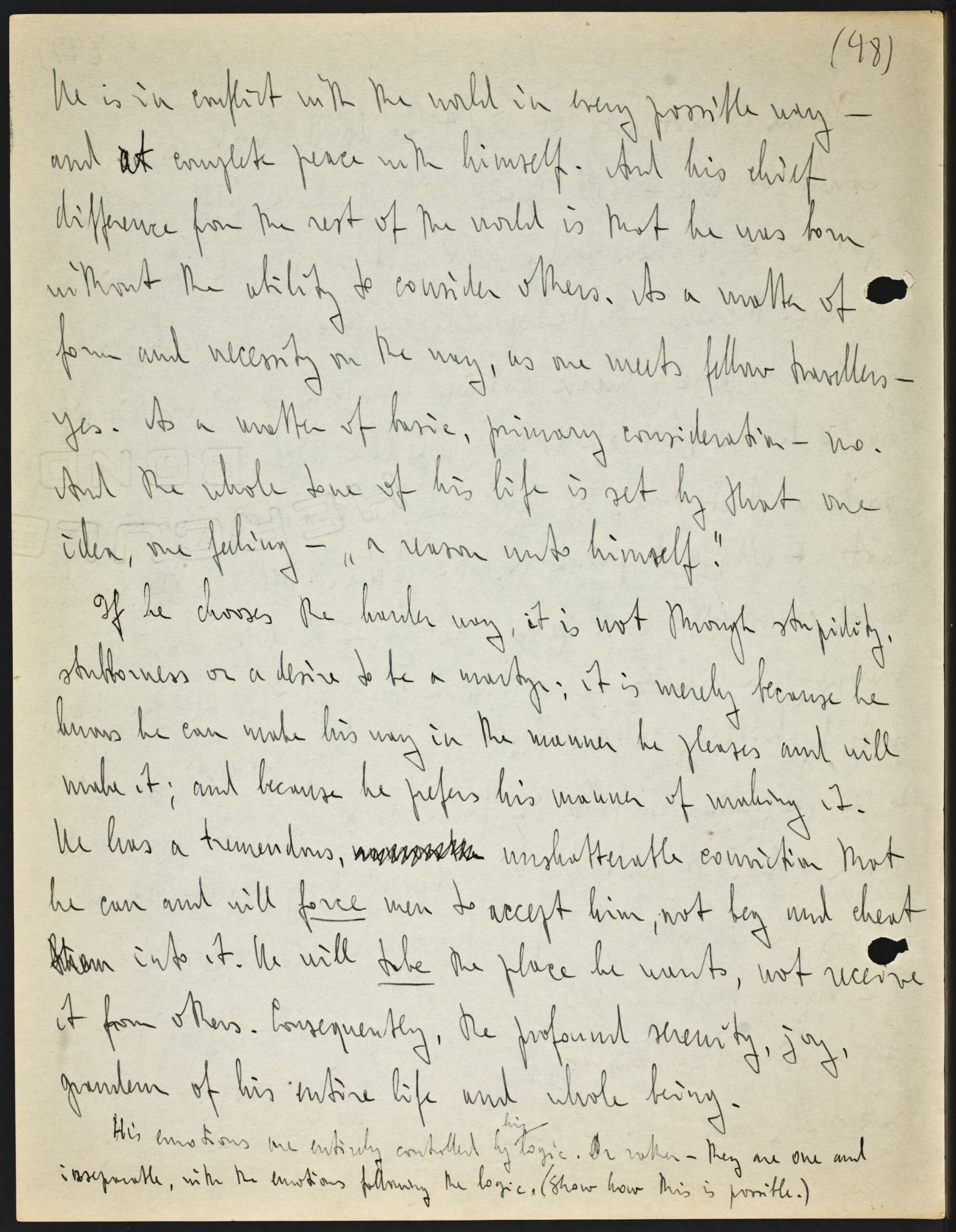

[Page 48]

(48)

He is in conflict with the world in every possible way – and in at complete peace with himself. And his chief difference from the rest of the world is that he was born without the ability to consider others. As a matter of form and necessity on the way, as one meets fellow travellers – yes. As a matter of basic, primary consideration – no. And the whole tone of his life is set by that one idea, one feeling – “a reason unto himself”.

If he chooses the harder way, it is not through stupidity, stubbornness or a desire to be a martyr; it is merely because he knows he can make his way in the manner he pleases and will make it; and because he prefers his manner of making it. He has a tremendous, [illegible] unshatterable conviction that he can and will force men to accept him, not beg and cheat them into it. He will take the place he wants, not receive it from others. Consequently, the profound security, joy, grandeur of his entire life and whole being.

His emotions are entirely controlled by his logic. Or rather – they are one and inseparable, with the emotions following the logic. (Show how this is possible.)

[Page 49]

(49)

His whole philosophy – pride in oneself, confidence in oneself, placing one’s life and fate above all, but only the kind of life he one wishes.

Religion – none. Not a speck of it. Born without any “religious brain center”. Does not understand or even conceive of the instinct for bowing and submission. His whole capacity for reverence is centered on himself. Needs no mystical “consolation”, no other life. Thinks too much of this world, to expect or desire any other.

Politics – interested only in not being interested in politics. Society as such does not exist for him. Other people do not interest him. He recognizes only the right of exceptions (and by that he means and knows only himself) to create, and order, and command. The others are to bow.

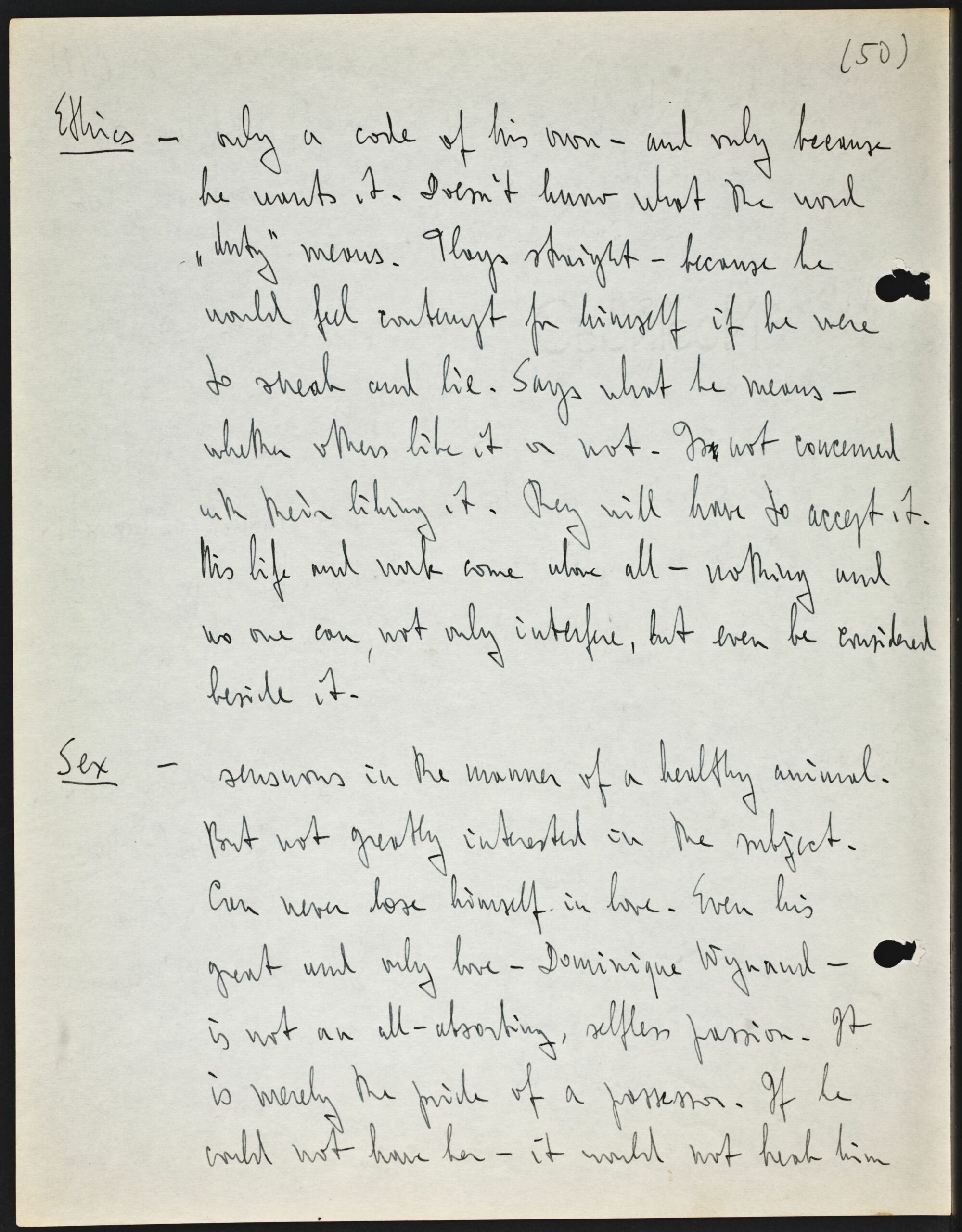

[Page 50]

(50)

Ethics – only a code of his own – and only because he wants it. Doesn’t know what the word “duty” means. Plays straight – because he would feel contempt for himself if he were to sneak and lie. Says what he means – whether others like it or not. Isn not concerned with their liking it. They will have to accept it. His life and work come above all – nothing and no one can, not only interfere, but even be considered beside it.

Sex – sensuous in the manner of a healthy animal. But not greatly interested in the subject. Can never lose himself in love. Even his great and only love – Dominique Wynand – is not an all-absorbing, selfless passion. It is merely the pride of a possessor. If he could not have her – it would not break him

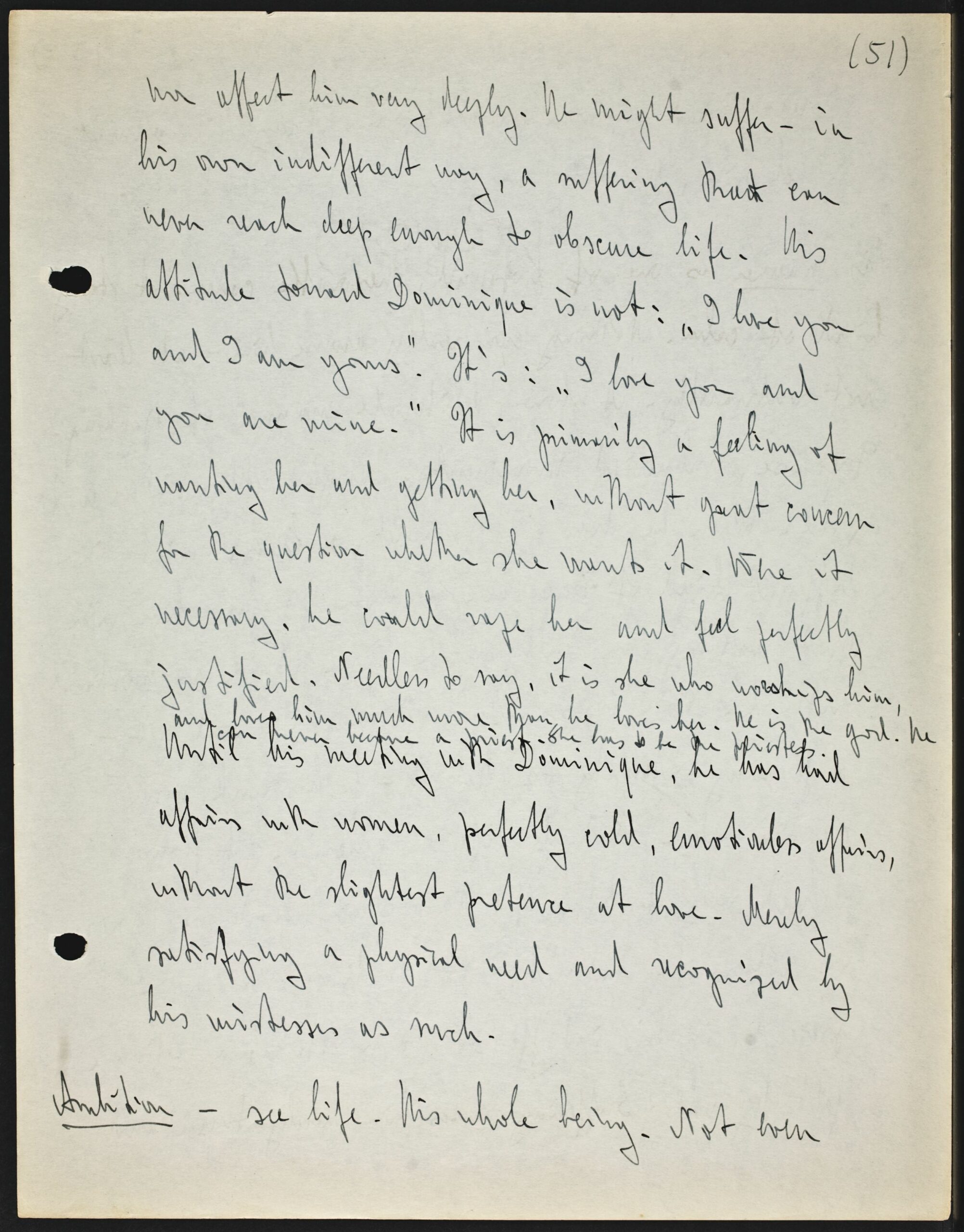

[Page 51]

(51)

nor affect him very deeply. He might suffer – in his own indifferent way, a suffering that can never reach deep enough to obscure life. His attitude toward Dominique is not: “I love you and I am yours.” It’s: “I love you and you are mine.” It is primarily a feeling of wanting her and getting her, without great concern for the question whether she wants it. Were it necessary, he could rape her and feel perfectly justified. Needless to say, it is she who worships him, and loves him much more than he loves her. He is the god. He can never become a priest. She has to be the priestess.

Until his meeting with Dominique, he has had affairs with women, perfectly cold, emotionless affairs, without the slightest pretence at love. Merely satisfying a physical need and recognized by his mistresses as such.

Ambition – see life. His whole being. Not even

[Page 52]

(52)

recognized by him as ambition. Merely his natural behavior, the only way he could be and act.

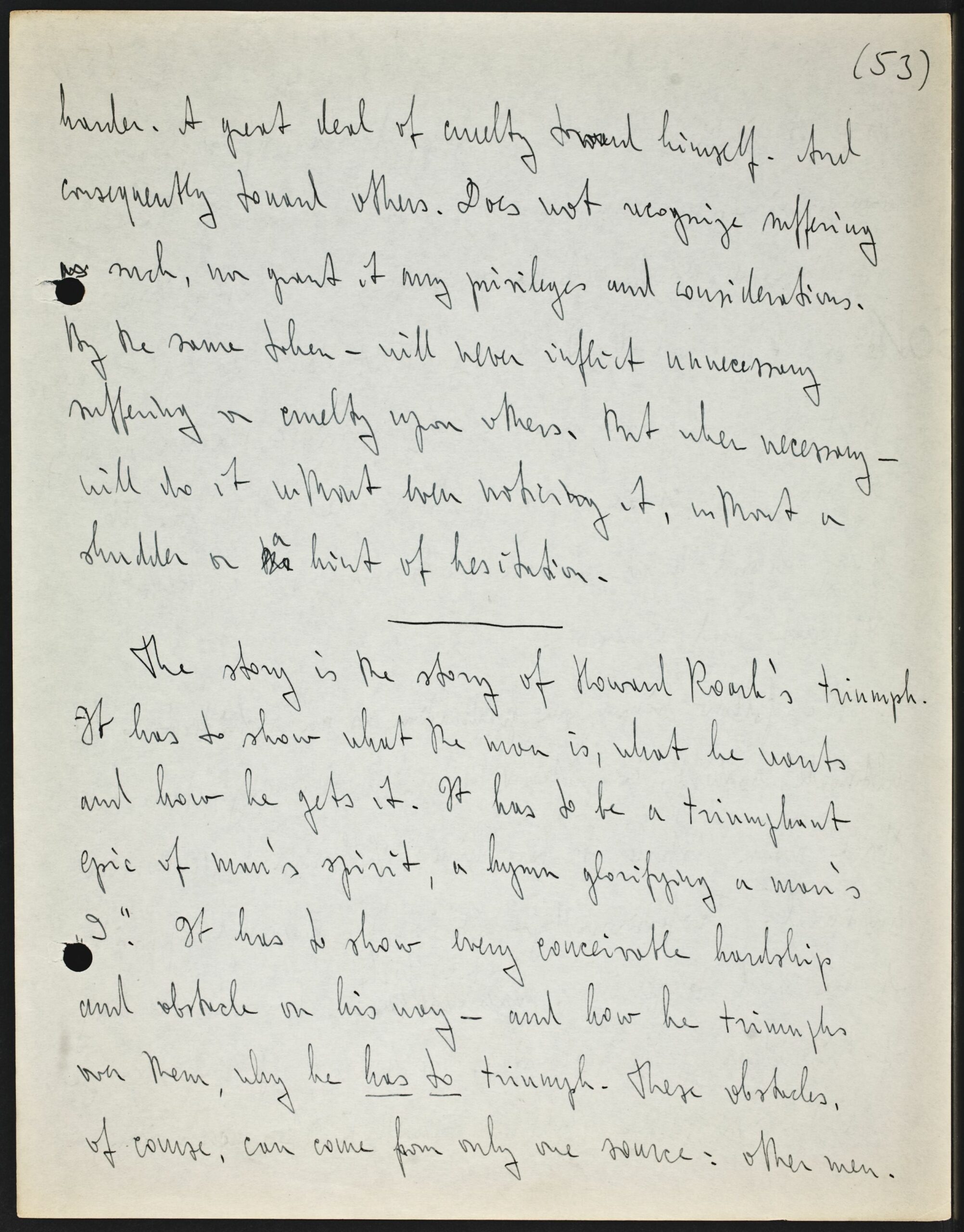

His manner is one of profound, inexorable calm. A [?strong] kind of calm. Nothing can really arouse him – at least not outwardly. A slow, deliberate manner of speaking. Precise, unhurried movements. Laughs seldom. Does not joke. When he does – it is merely a kind quiet, indifferent kind of sarcasm. A man so far above men that nothing can really reach him. Never an emotional outbreak. Never loses control of himself. And yet – a flaming intensity of feeling – for his work and creation only. And for life in general. A flame reserved only for himself. No one is ever to see, guess or witness it. And yet – its radiance is ever-present, in his indifferent calm itself, a radiance felt by all. Suffering makes him merely tenser and

[Page 53]

(53)

harder. A great deal of cruelty toward himself. And consequently toward others. Does not recognize suffering as such, nor grant it any privileges and considerations. By the same token – will never inflict unnecessary suffering or cruelty upon others. But when necessary – will do it without even noticing it, without a shudder or the a hint of hesitation.

The story is the story of Howard Roark’s triumph. It has to show what the man is, what he wants and how he gets it. It has to be a triumphant epic of man’s spirit, a hymn glorifying a man’s “I”. It has to show every conceivable hardship and obstacle on his way – and how he triumphs over them, why he has to triumph. These obstacles, of course, can come from only one source: other men.

[Page 54]

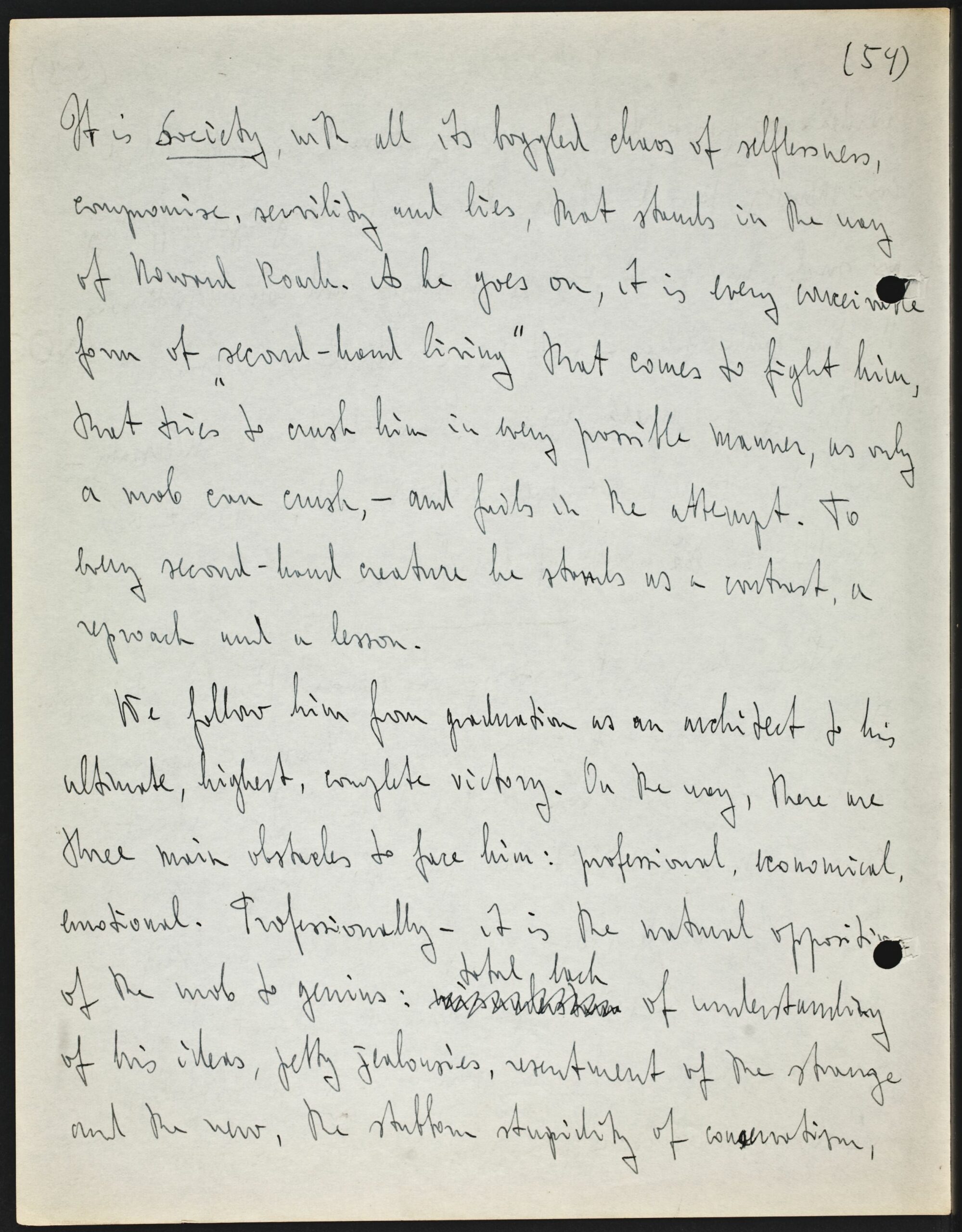

(54)

It is Society, with all its boggled chaos of selflessness, compromise, servility and lies, that stands in the way of Howard Roark. As he goes on, it is every conceivable form of “second-hand living” that comes to fight him, that tries to crush him in every possible manner, as only a mob can crush, – and fails in the attempt. To every second-hand creature he stands as a contrast, a reproach and a lesson.

We follow him from graduation as an architect to his ultimate, highest, complete victory. On the way, there are three main obstacles to face him: professional, economical, emotional. Professionally – it is the natural [?opposition] of the mob to genius: [?misunderstan] total lack of understanding of his ideas, petty jealousies, resentment of the strange and the new, the stubborn stupidity of conservatism,

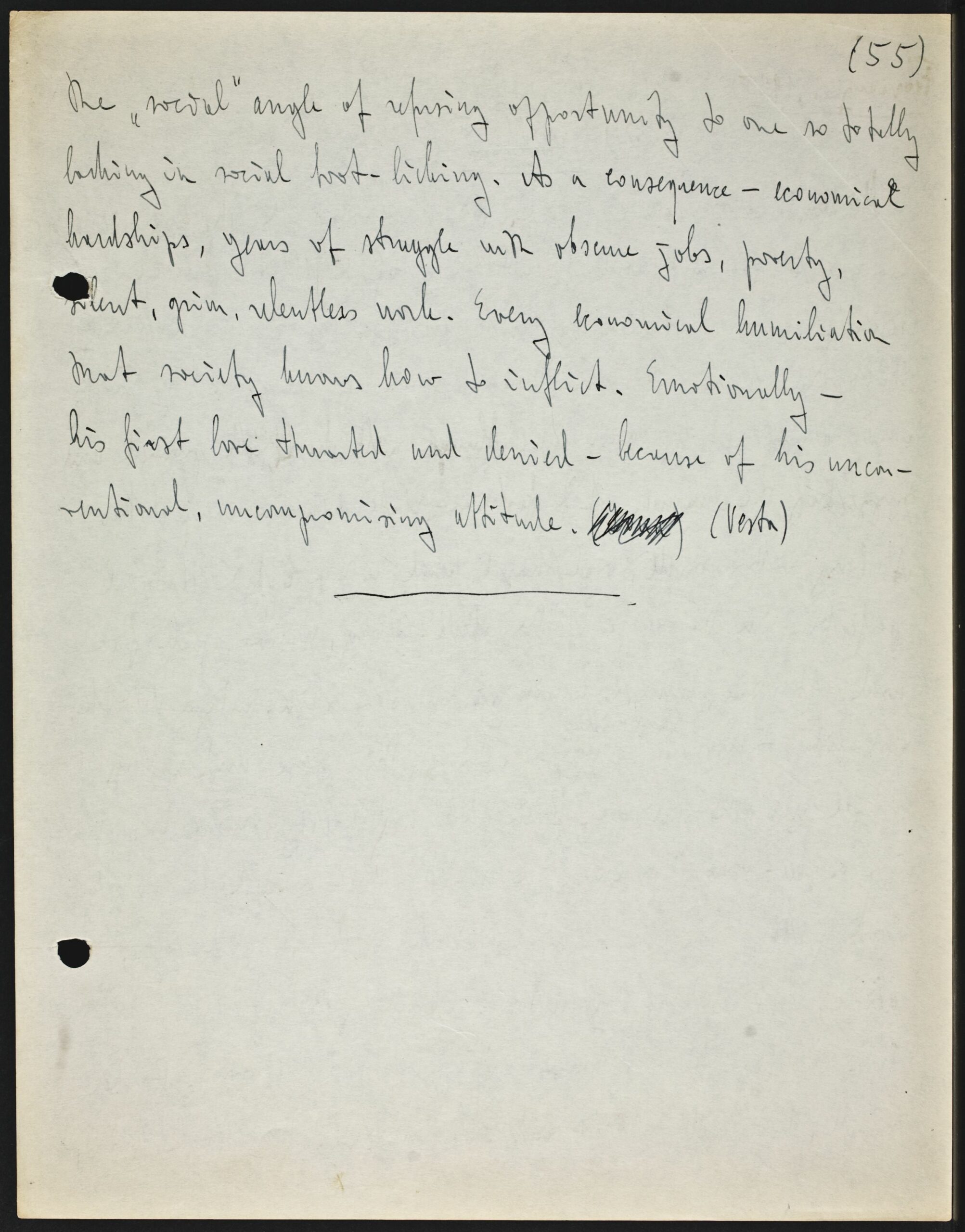

[Page 55]

(55)

the “social” angle of refusing opportunity to one so totally lacking in social boot-licking. As a consequence – economical hardships, years of struggle with obscure jobs, poverty, silent, grim, relentless work. Every economical humiliation that society knows how to inflict. Emotionally – his first love thwarted and denied – because of his unconventional, uncompromising attitude. (Lona) (Vesta)

[Page 56]

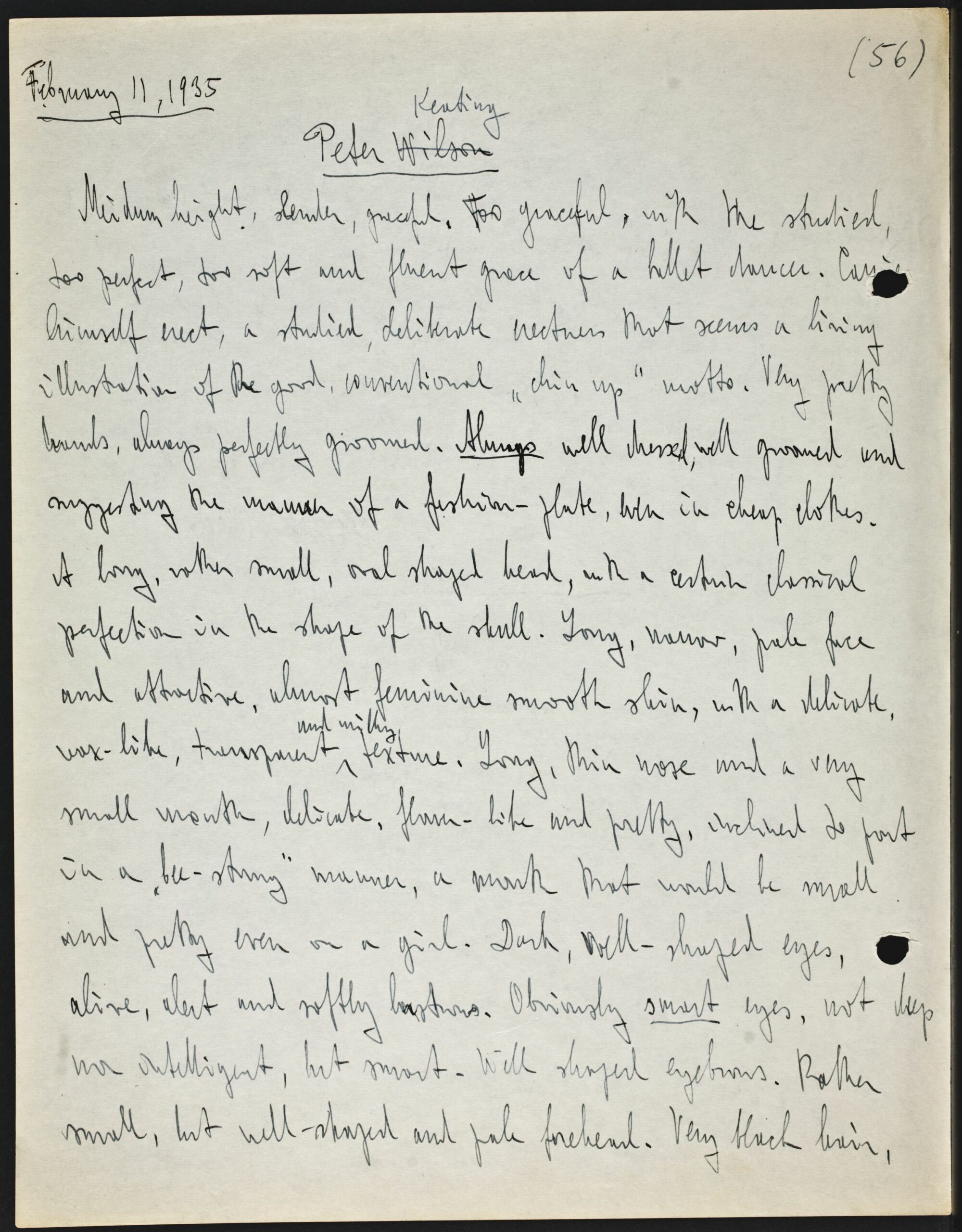

(56)

February 11, 1935

Peter Wilson Keating

Meidum height, slender, graceful. Too graceful, with the studied, too perfect, too soft and fluent grace of a ballet dancer. [?Carries] himself erect, a studied, deliberate erectness that seems a living illustration of the good, conventional “chin up” motto. Very pretty hands, always perfectly groomed. Always well dressed, well groomed and suggesting the manner of a fashion-plate, even in cheap clothes. A long, rather small, oval shaped head, with a certain classical perfection in the shape of the skull. Long, narrow, pale face and attractive, almost feminine smooth skin, with a delicate, wax-like, transparent and milky texture. Long, thin nose and a very small mouth, delicate, flower-like and pretty, inclined to pout in a “bee-stung” manner, a mouth that would be small and pretty even on a girl. Dark, well-shaped eyes, alive, alert and softly lustrous. Obviously smart eyes, not deep nor intelligent, but smart. Well shaped eyebrows. Rather small, but well-shaped and pale forehead. Very black hair,

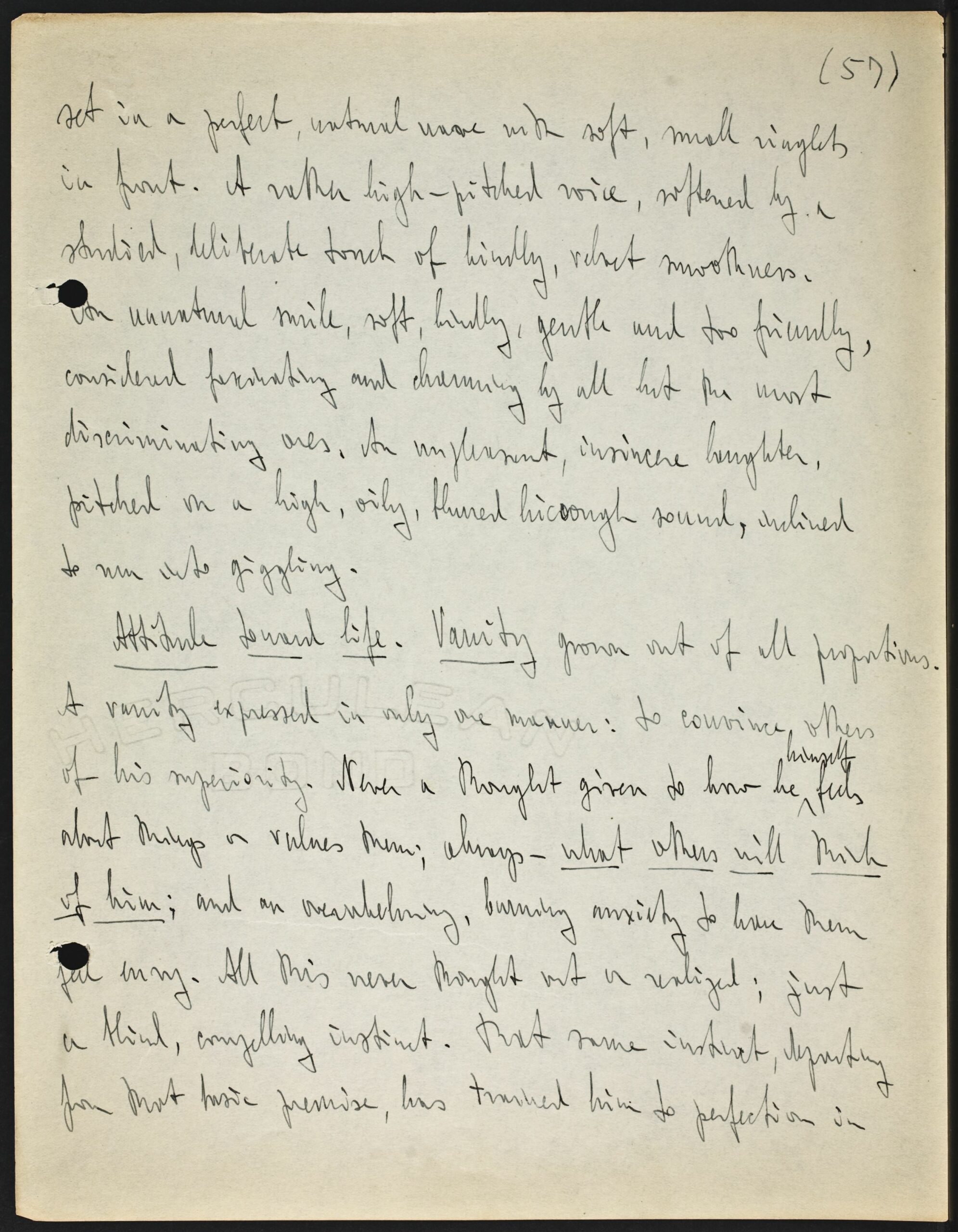

[Page 57]

(57)

set in a perfect, natural wave with soft, small ringlets in front. A rather high-pitched voice, softened by a studied, deliberate touch of kindly, velvet smoothness. An unnatural smile, soft, kindly, gentle and too friendly, considered fascinating and charming by all but the most discriminating ones. An unpleasant, insincere laughter, pitched on a high, oily, blurred hiccough sound, inclined to run into giggling.

Attitude toward life. Vanity grown out of all proportions. A vanity expressed in only one manner: to convince others of his superiority. Never a thought given to how he himself feels about things or values them; always – what others will think of him; and an overwhelming, burning anxiety to have them feel envy. All this never thought out or realized; just a blind, compelling instinct. That same instinct, departing from that basic premise, has trained him to perfection in

[Page 58]

(578)

[page otherwise blank, crossed out]

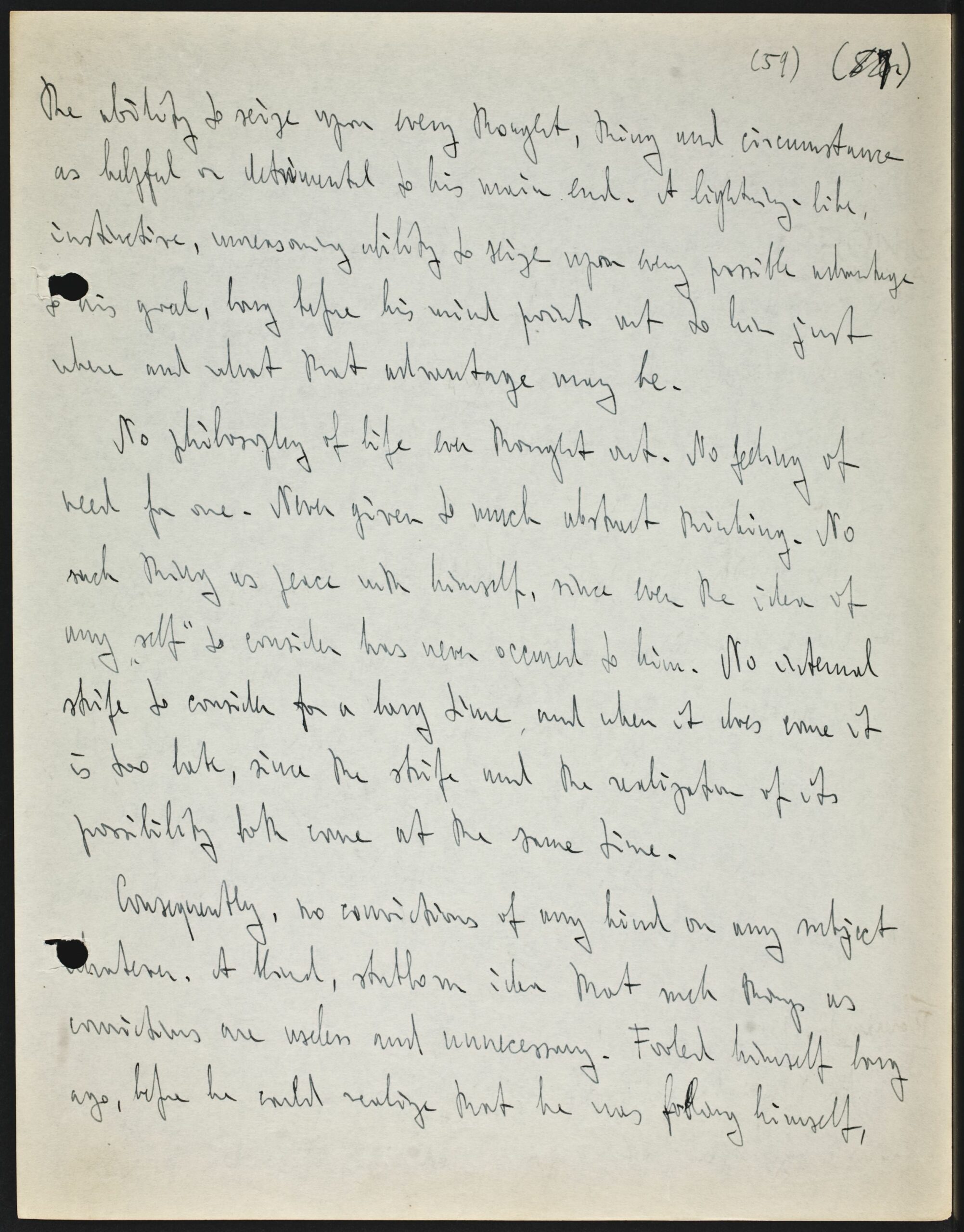

[Page 59]

(59) (58<7>)

the ability to seize upon every thought, thing and circumstance as helpful or detrimental to his main end. A lightning-like, instinctive, unreasoning ability to seize upon every possible advantage to his goal, long before his mind points out to him just where and what that advantage may be.

No philosophy of life ever thought out. No feeling of need for one. Never given to much abstract thinking. No such thing as peace with himself, since even the idea of any “self” to consider has never occurred to him. No internal strife to consider for a long time, and when it does come it is too late, since the strife and the realization of its possibility both came at the same time.

Consequently, no convictions of any kind on any subject whatever. A blind, stubborn idea that such things as convictions are useless and unnecessary. Fooled himself long ago, before he could realize that he was fooling himself,

[Page 60]

(60) (58)

into the belief that his superiority lays precisely in his freedom from all bounds of conviction. Only an instinctive, subconscious resentment and impatient annoyance with [?those] he considers “idealists” left in him as a reminder of his unrealized, but subconsciously felt inferiority. Which drives him, in self-protection, into a bitter, vicious resentment of men “with ideas”.

His main principle – “don’t take anything seriously”. A cheap cynicism and iconoclastic fury against everything high, noble and exceptional parade under the cloak of a “sense of humor”, “horse common sense”, “practical sense” and “keeping your feet on the ground”. Defending as “reality” all that he wishes reality to be.

February 12, 1936

An invariable habit of belittling, mocking and dragging down everything high. Greatly enjoys “debunking” biographies of famous

[Page 61]

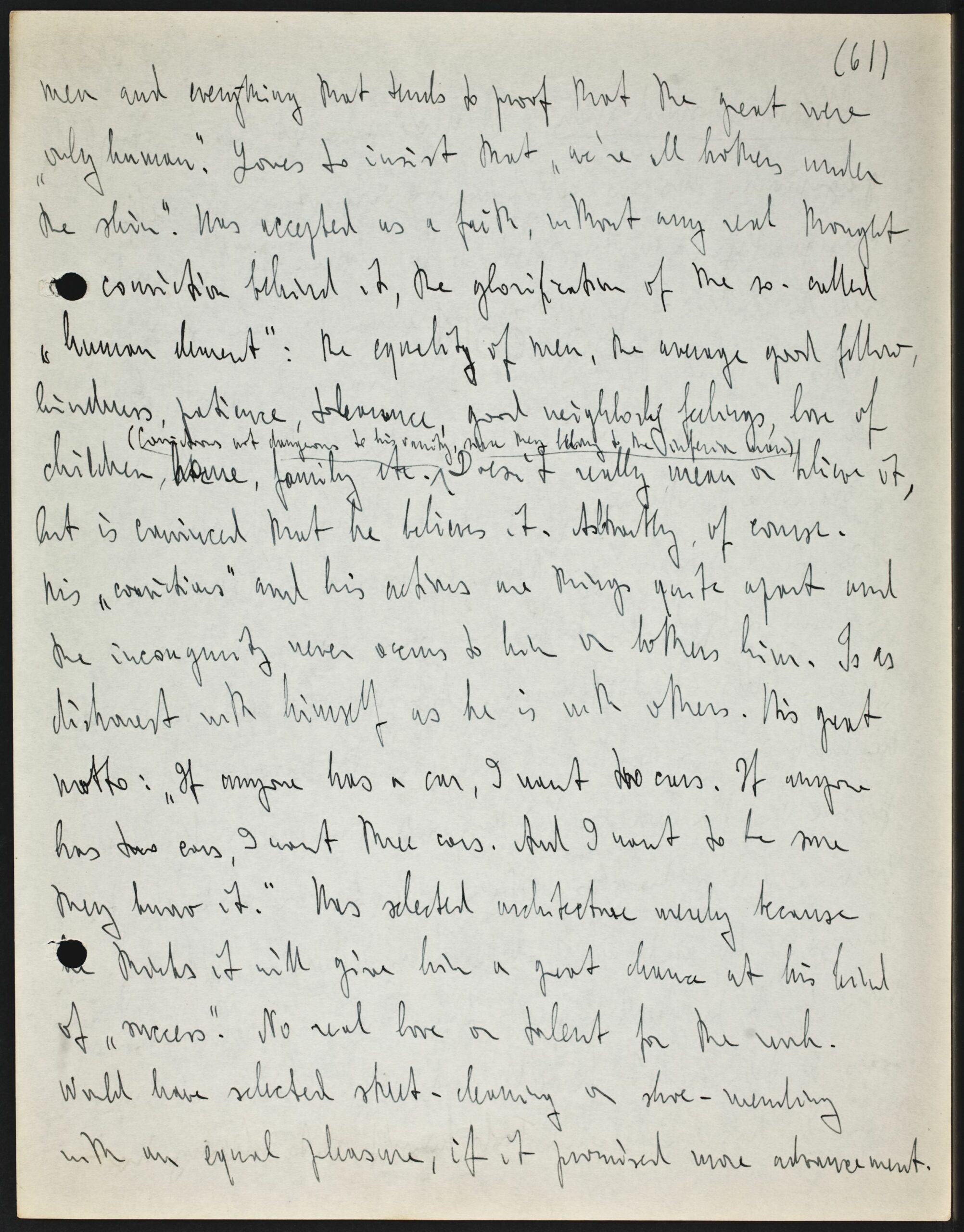

(61)

men and everything that tends to proof that the great were “only human”. Loves to insist that “we’re all brothers under the skin”. Has accepted as a faith, without any real thought [?or] conviction behind it, the glorification of the so-called “human element”: the equality of men, the average good fellow, kindness, patience, tolerance, good neighborly feelings, love of children, home, family etc. (Convictions not dangerous to his vanity, since they belong to the inferior man) Doesn’t really mean or believe it, but is convinced that he believes it. Asbtractly, of course. His “convictions” and his actions are things quite apart and the incongruity never occurs to him or bothers him. Is as dishonest with himself as he is with others. His great motto: “If anyone has a car, I want two cars. If anyone has two cars, I want three cars. And I want to be sure they know it.” Has selected architecture merely because [?he] thinks it will give him a great chance at his kind of “success.” No real love or talent for the work. Would have selected street-cleaning or shoe-mending with an equal pleasure, if it promised more advancement.

[Page 62]

(62)

Attitude toward men A mob men at heart. Completely gregarious. Has no satisfaction or interest in himself, consequently cannot stand to be alone. Prefers and selects inferior people among whom he can shine. Talks a great deal about the “communal spirit”, but sees to it that he is always the leader of any “commune”. Always plays up to others and revels in his great popularity. Never expresses a definite opinion on any subject, be it the weather. Always sits on the fence. Calls it diplomacy. Acts as if each new man he meets is his greatest friend and the most interesting person in the world. Listens with immense interest to everyone else’s troubles. Never remembers a word of it. Always ready and delighted to help others – and h says so. Never forgets to mention past favors he has rendered. Loves to take credit for all and any achievement of those he has ever helped. Fools himself into believing that

[Page 63]

(63)

he is sincere in his altruism. Doesn’t realize that it is caused by the subconscious instinct that tells him this altruism will help him a great deal in his cause, his vanity, in the [?opinions] of others. But will never lift a finger if helping another would really cost him anything or if there is no glory in such helping. And would not hesitate to cut as many throats as may be and as unnecessarily as may be if he thinks it will help him.

Loves movies and popular plays and vaudeville and, occasionally, magazines of the “Liberty” kind. Loves best-selling novels, particularly the “human interest” ones. Feels genuine respect for anything that has proved popular or has made money, no matter what he himself may have thought about it. Prefers stories about mothers, children and dogs. Loves animals and declares them superior to men. Donates to orphan asylums and charit societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals. Shruggs at old

[Page 64]

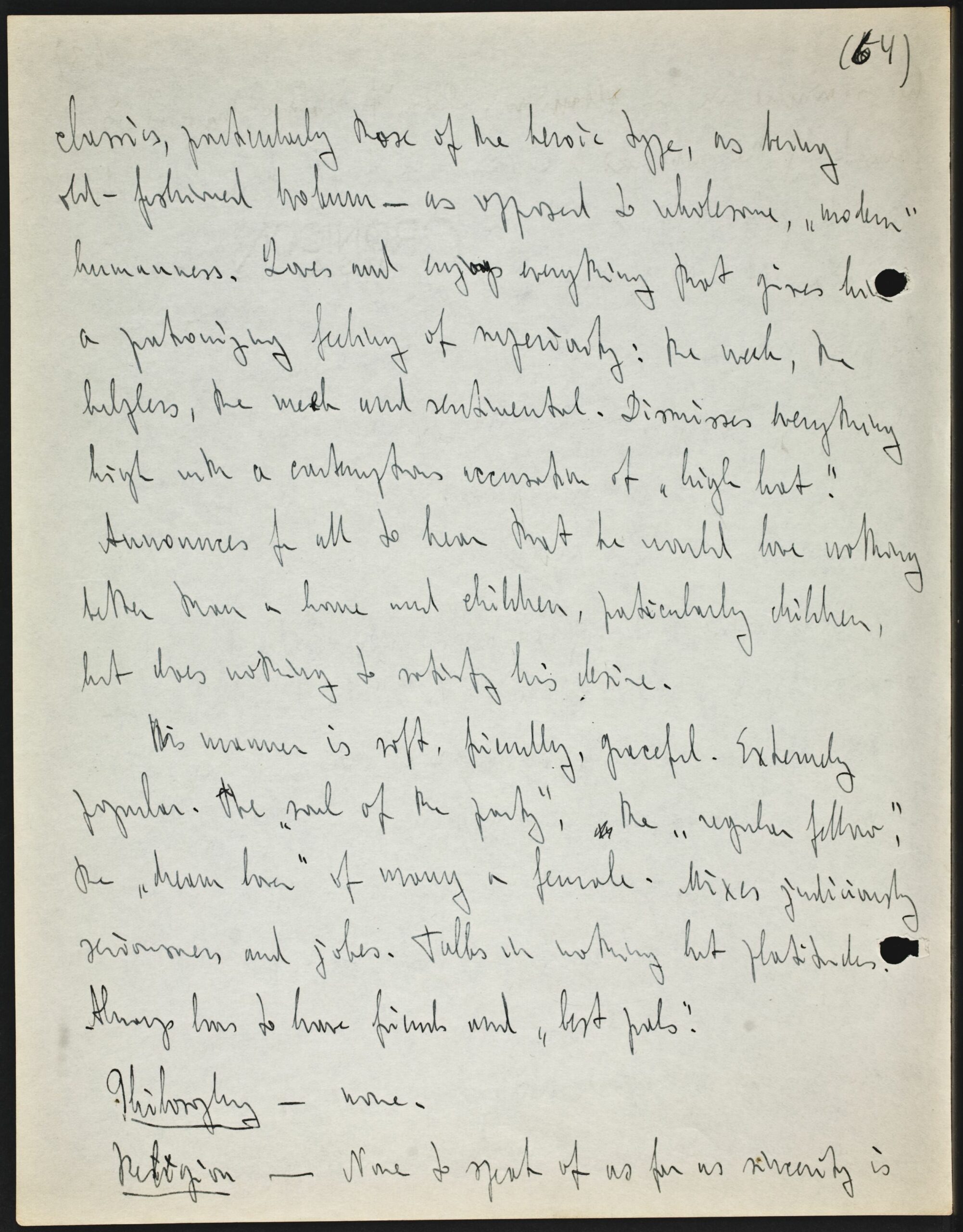

(564)

classics, particularly those of the heroic type, as being old-fashioned hokum – as opposed to wholesome, “modern” humanness. Loves and enjoys everything that gives him a patronizing feeling of superiority: the weak, the helpless, the meek and sentimental. Dismisses everything high with a contemptuous accusation of “high hat”. Announces for all to hear that he would love nothing better than a home and children, particularly children, but does nothing to satisfy his desire.

His manner is soft, friendly, graceful. Extremely popular. The “soul of the party”, “the “regular fellow”, the “dream lover” of many a female. Mixes judiciously seriousness and jokes. Talks in nothing but platitudes. Always has to have friends and “best pals”.

Philosophy – none.

Religion – None to speak of as far as sincerity is

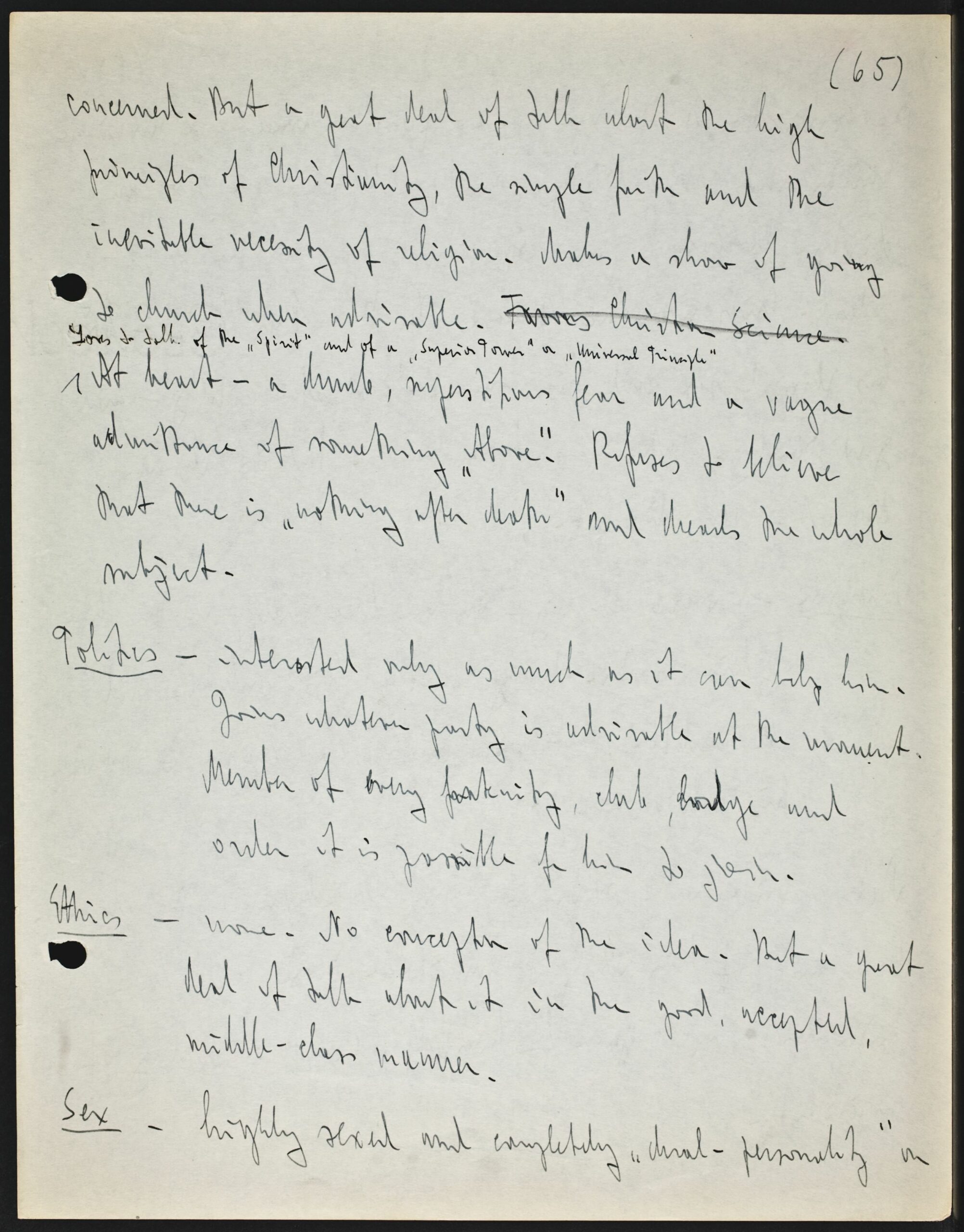

[Page 65]

(65)

concerned. But a great deal of talk about the high principles of Christianity, the simple faith and the inevitable necessity of religion. Makes a show of going to church when advisable. Favors Christian Science. Loves to talk of the “Spirit” and of a “Superior Power” or “Universal Principle” At heart – a dumb, superstitious fear and a vague admittance of something “Above”. Refuses to believe that there is “nothing after death” and dreads the whole subject.

Politics – interested only as much as it can help him. Joins whatever party is advisable at the moment. Member of every fraternity, club, lodge and order it is possible for him to join.

Ethics – none. No conception of the idea. But a great deal of talk about it in the good, accepted, middle-class manner.

Sex – highly sexed and completely “dual-personality” on

[Page 66]

(66)

the subject. On the one hand – preaches home-love, marriage, purity and respectability. Considers physical sex low and dirty. Proclaims pure, Spiritual love as the perfect ideal. Cries over love stories. On the other hand – loves his physical sex and his women. Dissipates wildly – and judiciously. Patronizes whore houses. But is always discreet – very discreet.

Ambition – overwhelming – in one line only, on the line of his vanity. Always belittles his ambition and all ambitions, but never misses a chance to mention his achievements.

Acts servile with superiors and overbearing with inferiors. Goes out of his way to humiliate those under him, with nothing to gain for himself, except a feeling of superiority.

[Page 67]

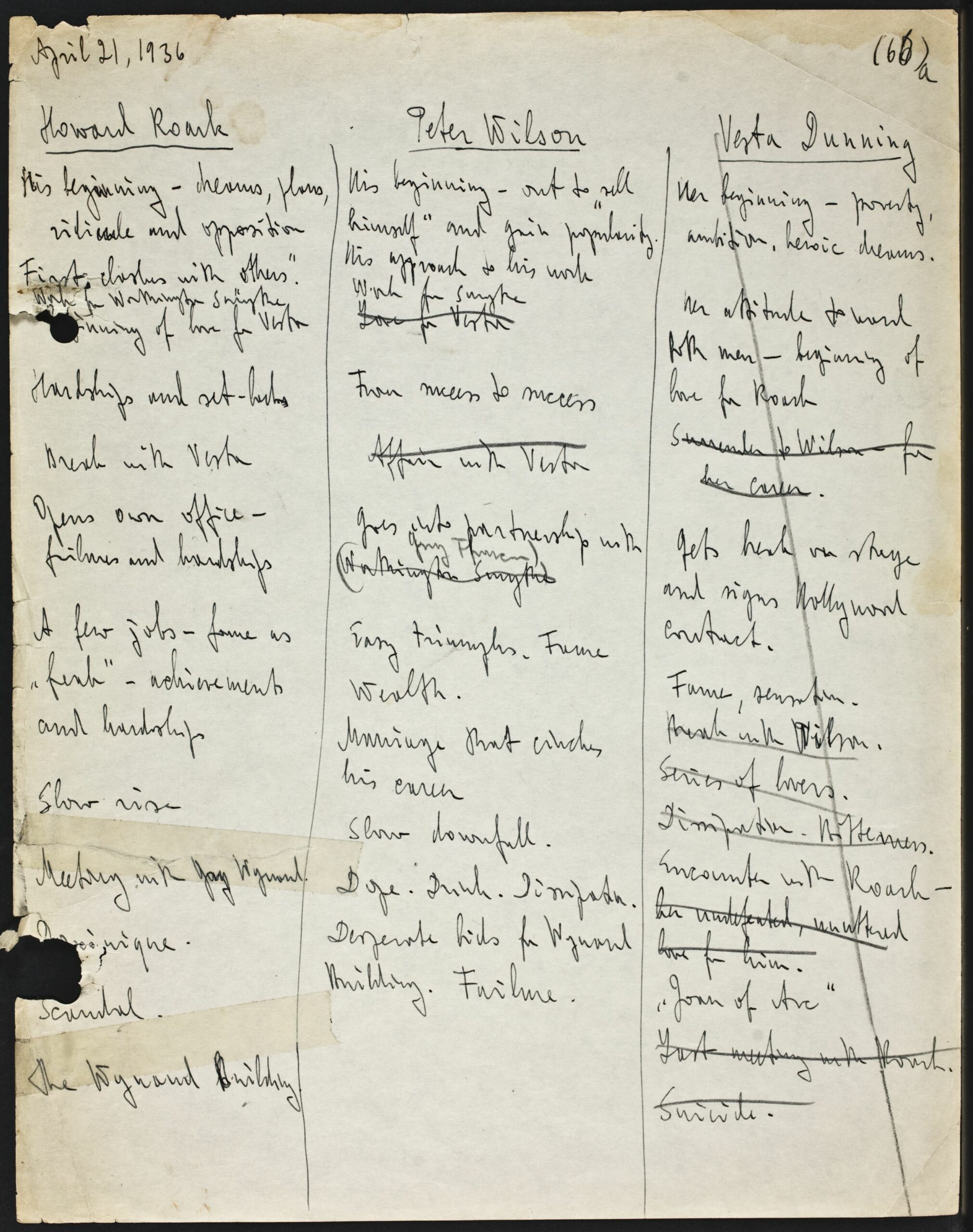

(676)a

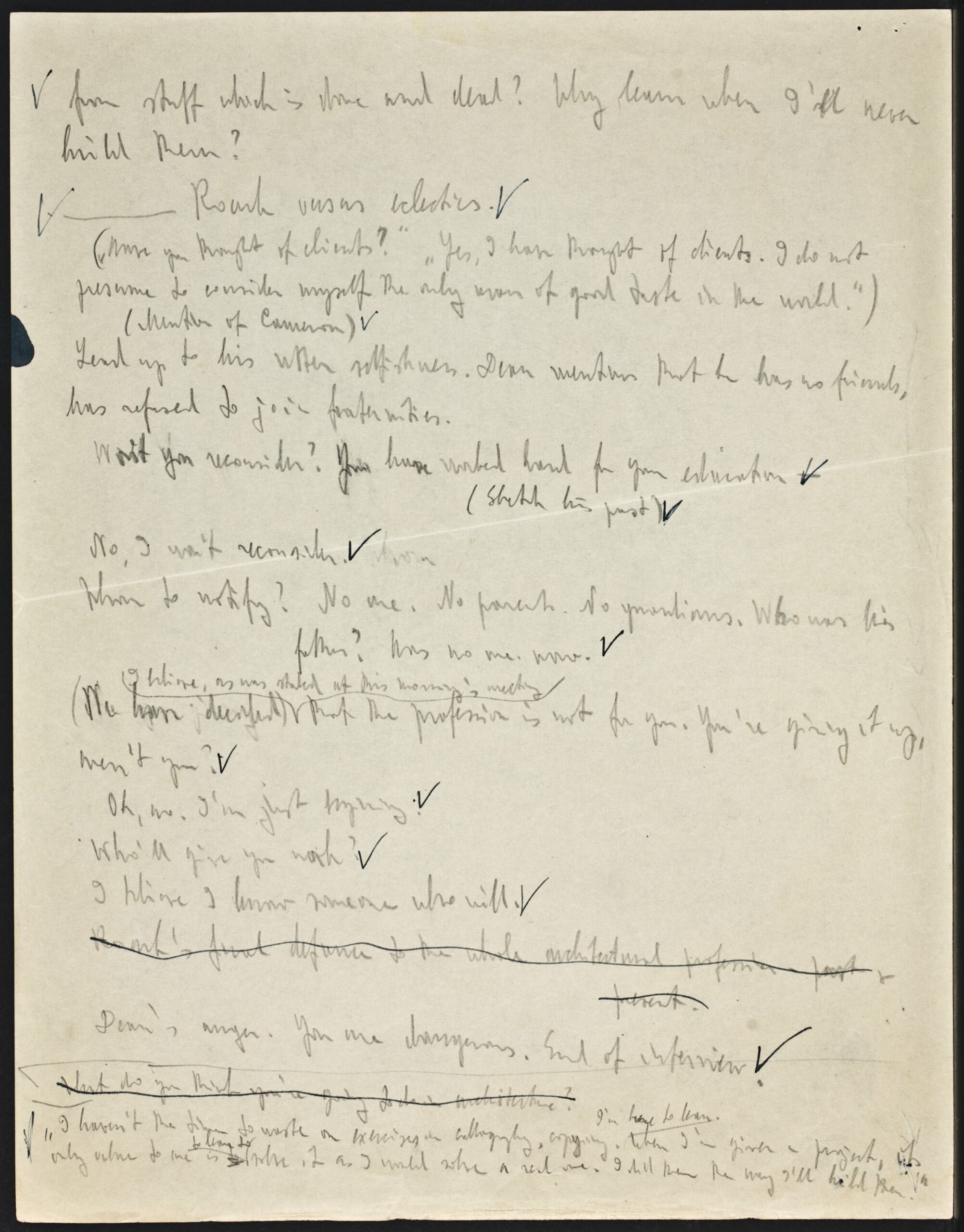

April 21, 1936

[Column 1 of 3]

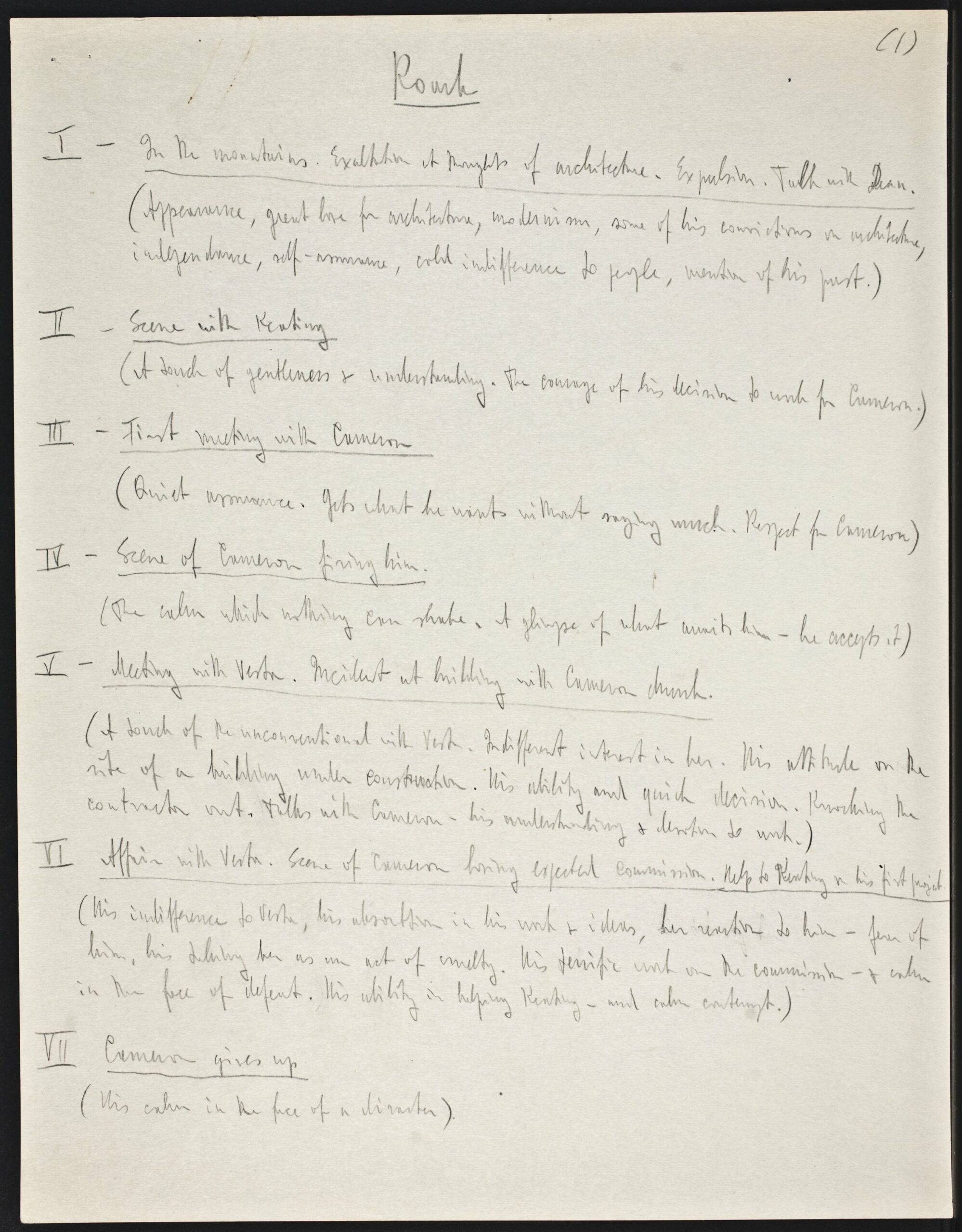

Howard Roark

His beginning – dreams, plans, ridicule and opposition

First clashes with “others”.

Work for Worthington Smythe

[?Beginning] of love for Vesta

Hardships and set-backs

Break with Vesta

Opens own office – failures and hardships

A few jobs – fame as “freak” – achievements and hardships

Slow rise

Meeting with Gay Wynand.

Dominique.

Scandal.

The Wynand Building.

[Column 2 of 3]

Peter Wilson

His beginning – out to “sell himself” and gain popularity.

His approach to his work

Work for Smythe

Love for Vesta

From success to success

Affair with Vesta

Goes into partnership with (Worthington Smythe Guy Ffrancon)

Easy triumphs. Fame

Wealth.

Marriage that cinches his career

Slow downfall.

Dope. Drink. Dissipation.

Desperate bids for Wynand Building. Failure.

[Column 3 of 3 – whole column struck out later]

Vesta Dunning

Her beginning – poverty, ambition, heroic dreams.

Her attitude toward both men – beginning of love for Roark

Surrender to Wilson – for her career.

Gets break on stage and signs Hollywood contract.

Fame, sensation.

Break with Wilson.

Series of lovers.

Dissipation. Bitterness.

Encounter with Roark – her undefeated, unuttered love for him.

“Joan of Arc”

Last meeting with Roark.

Suicide.

[Page 68]

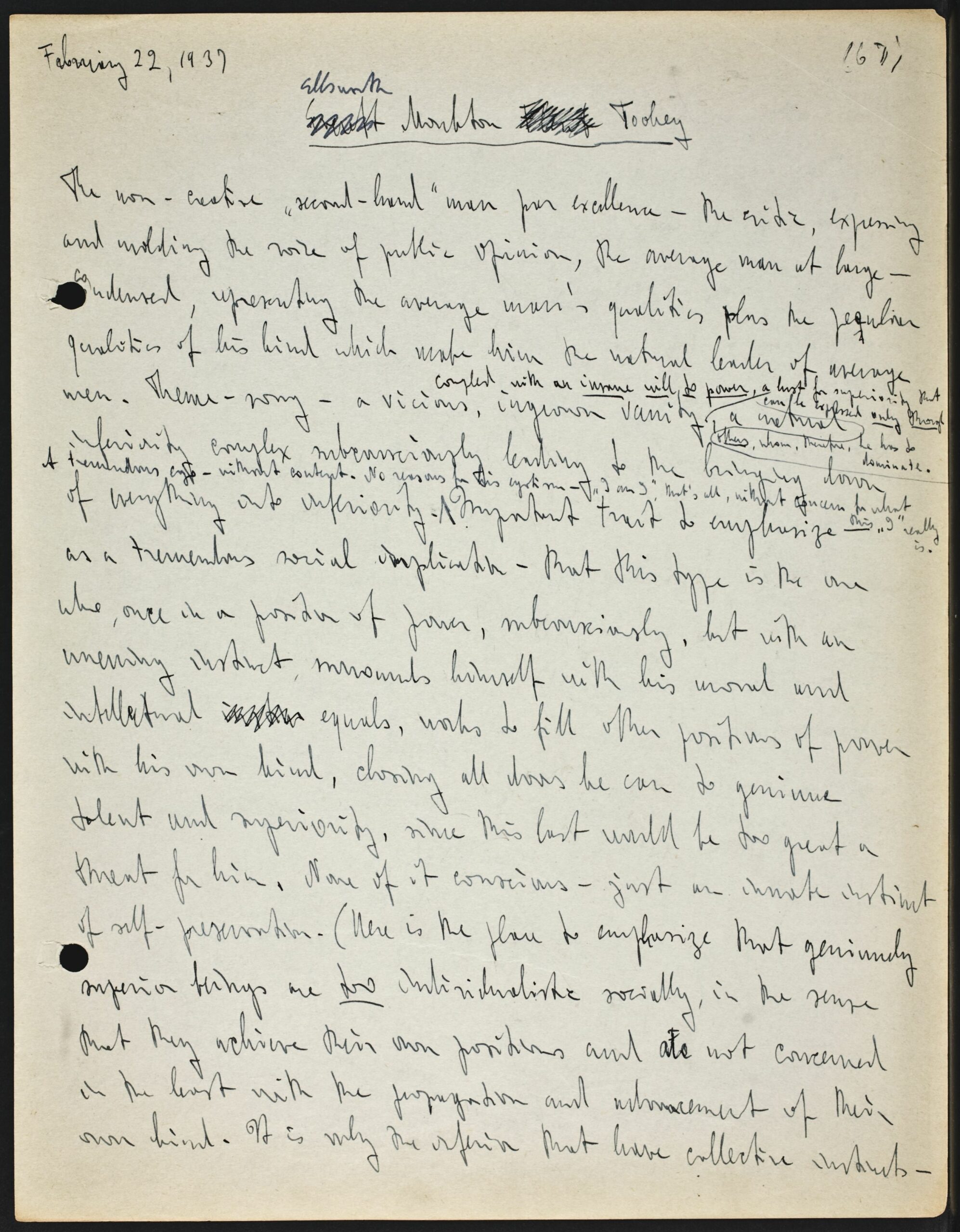

(67)

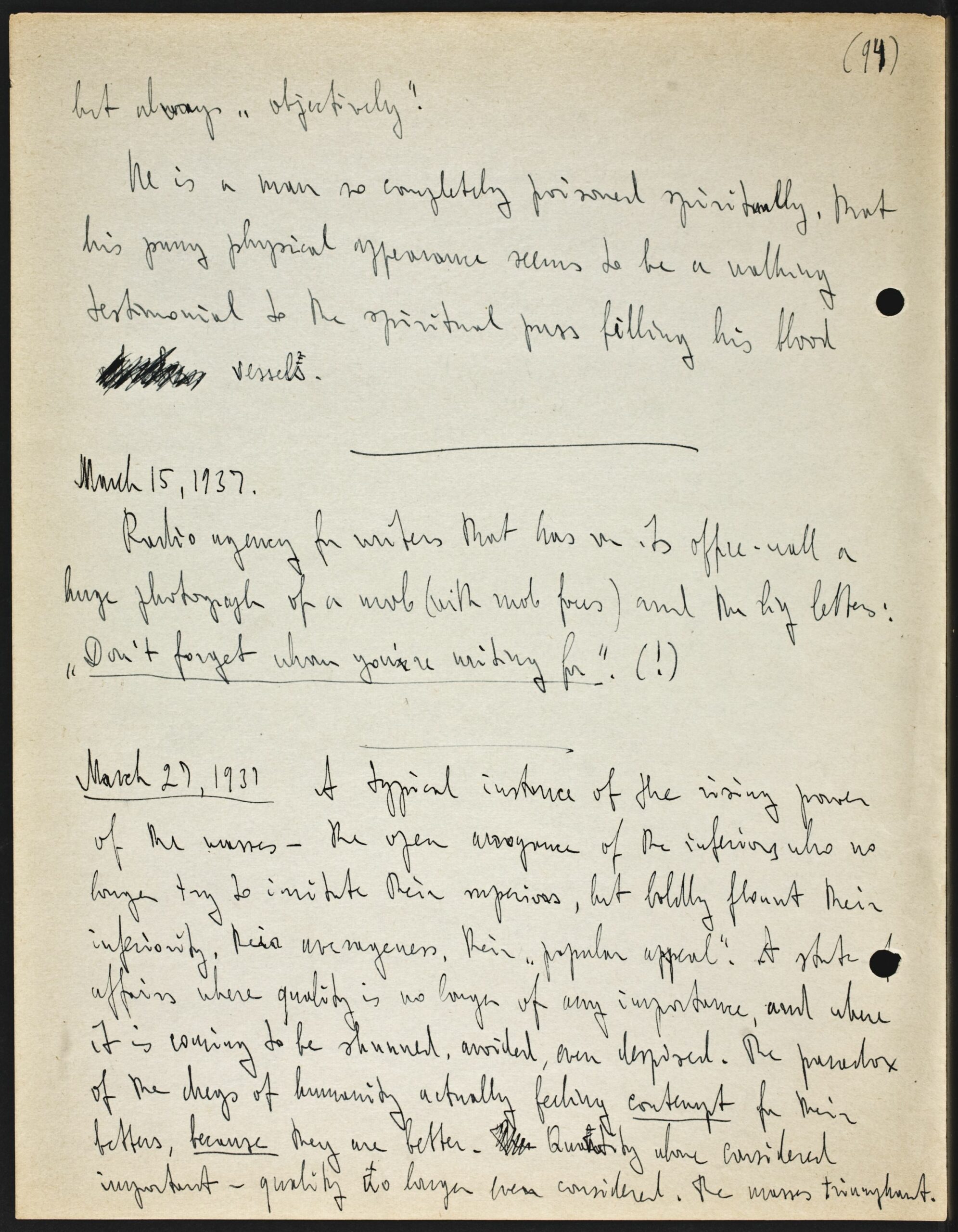

February 22, 1937

Everett Ellsworth Monkton [?Flent] Toohey

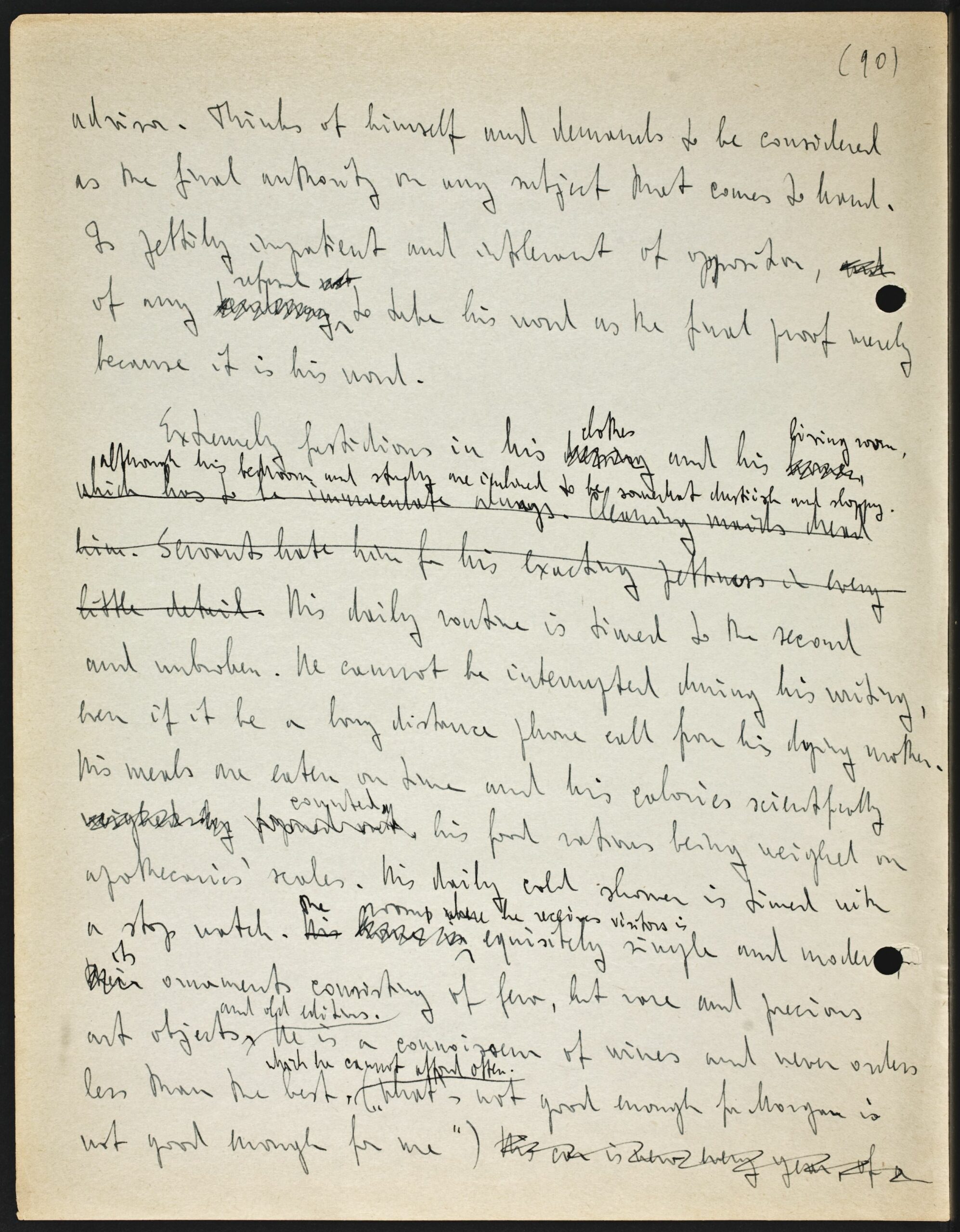

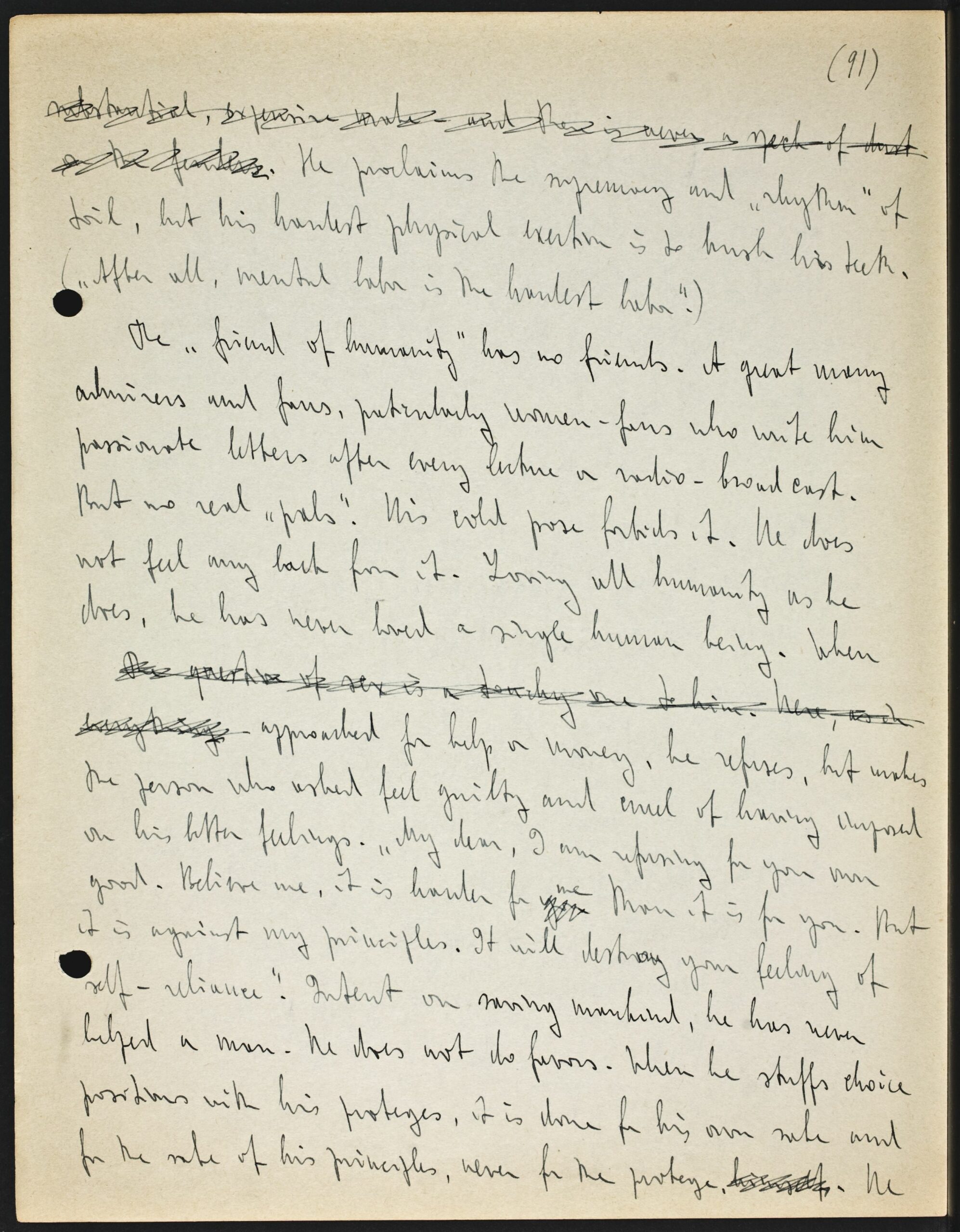

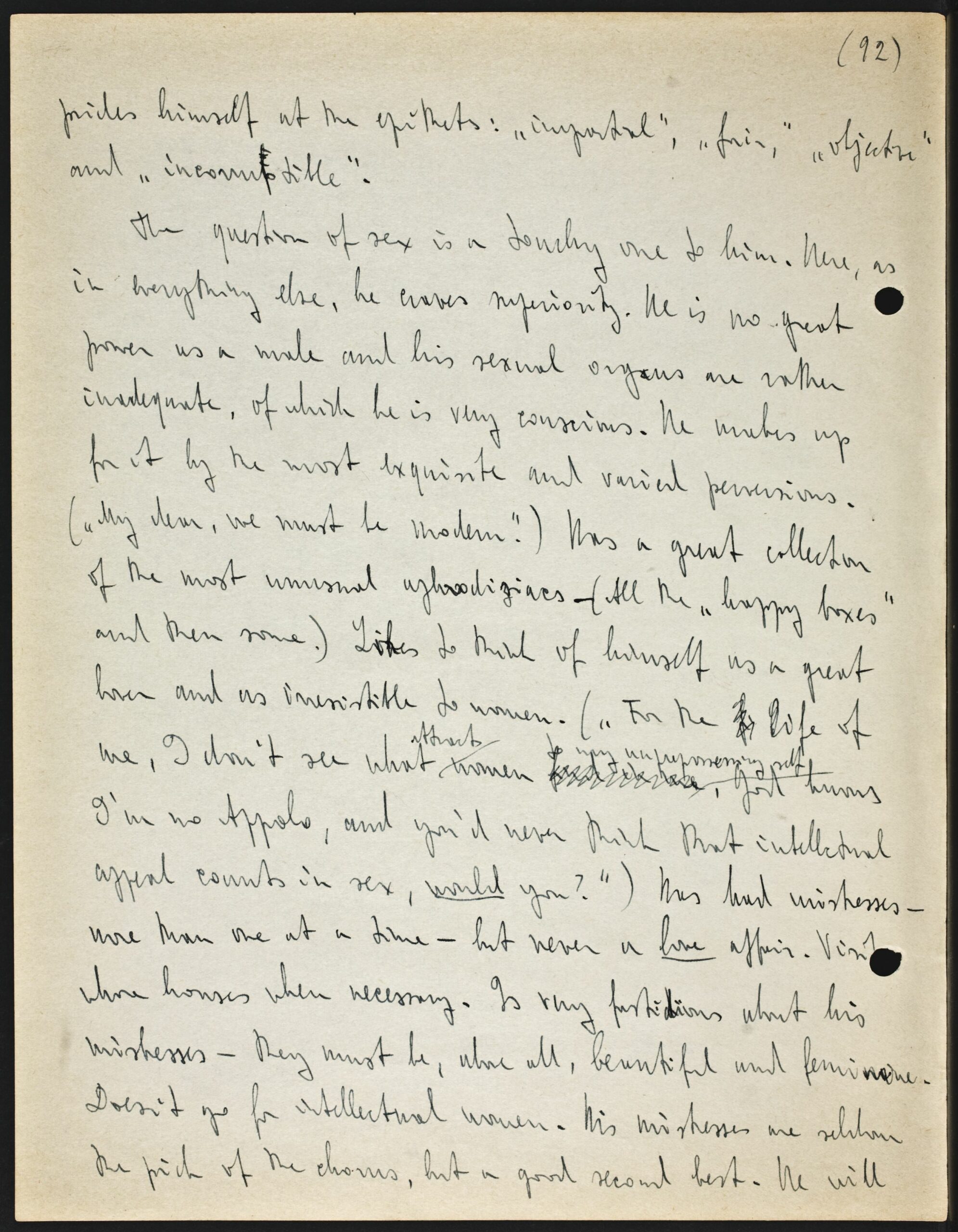

The non-creative “second-hand” man par excellence – the critic, expressing and molding the voice of public opinion, the average man at large – condensed, representing the average man’s qualities plus the peculiar qualities of his kind which make him the natural leader of average men. Theme-song – a vicious, ingrown vanity coupled with an insane will to power, a lust for superiority that can be expressed only through others, whom, therefore, he has to dominate. a natural inferiority complex subconsciously leading to the bringing down of everything into inferiority. A tremendous ego – without content. No reasons for his egotism – “I am I”, that’s all, without concern for what this “I” really is. Important trait to emphasize – as a tremendous social implication – that this type is the one who, once in a position of power, subconsciously, but with an unerring instinct, surrounds himself with his moral and intellectual [?instinc] equals, works to fill other positions of power with his own kind, closing all doors he can to genuine talent and superiority, since this last would be too great a threat for him. None of it conscious – just an innate instinct of self-preservation. (Here is the place to emphasize that genuinely superior beings are too individualistic socially, in the sense that they achieve their own positions and are not concerned in the least with the propagation and advancement of their own kind. It is only the inferior that have collective instincts –

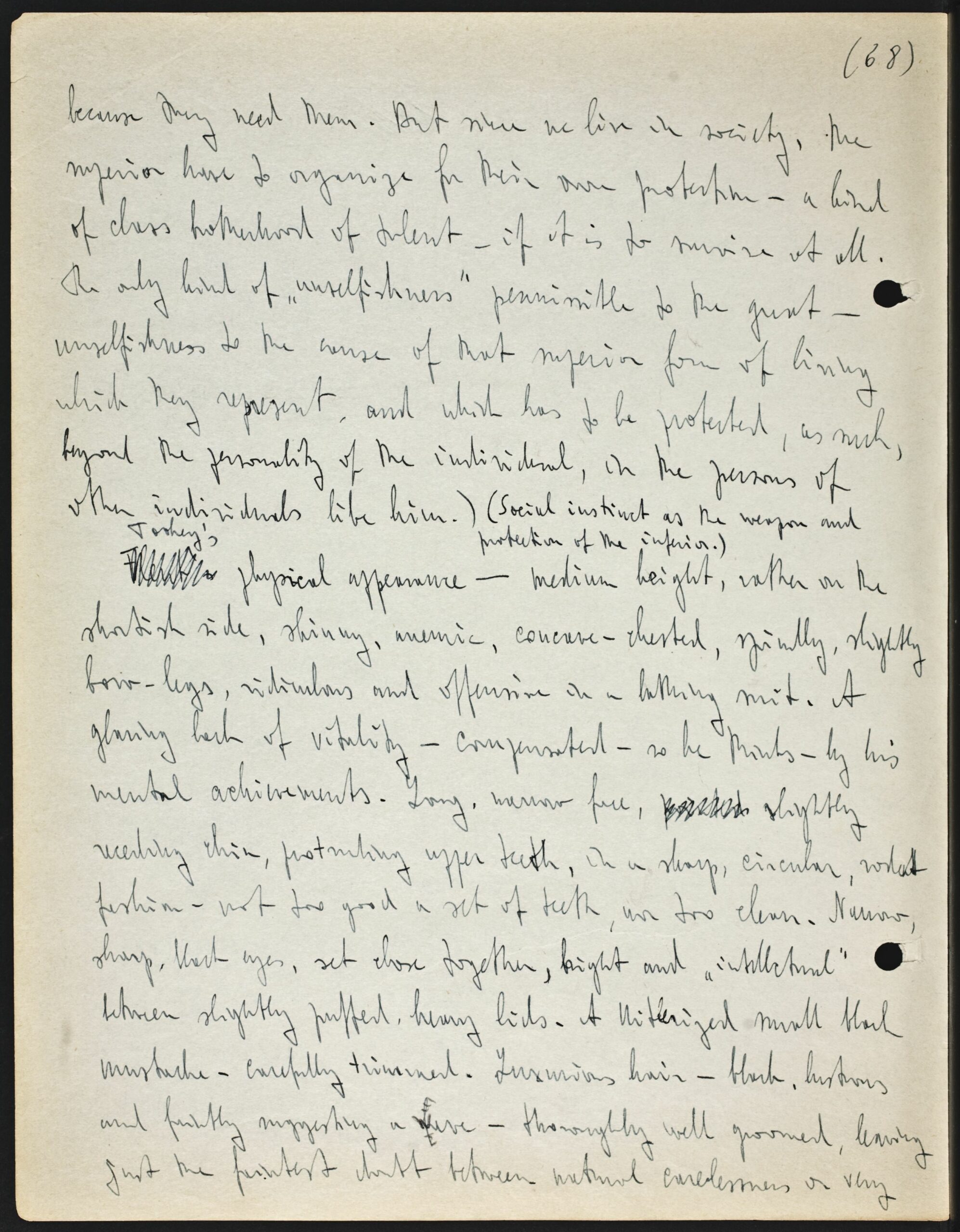

[Page 69]

(68)

because they need them. But since we live in society, the superior have to organize for their own protection – a kind of class brotherhood of talent – if it is to survive at all. The only kind of “unselfishness” permissible to the great – unselfishness to the cause of that superior form of living which they represent, and which has to be protected, as such, beyond the personality of the individual, in the persons of other individuals like him.) (Social instinct as the weapon and protection of the inferior.)

[?Flent’s] Toohey’s physical appearance – medium height, rather on the shortish side, skinny, anemic, concave-chested, spindly, slightly bow-legs, ridiculous and offensive in a bathing suit. A glaring lack of vitality – compensated – so he thinks – by his mental achievements. Long, narrow face, pointed slightly receding chin, protruding upper teeth, in a sharp, circular, rodent fashion – not too good a set of teeth, nor too clean. Narrow, sharp, black eyes, set close together, bright and “intellectual” between slightly puffed, heavy lids. A Hitlerized small black mustache – carefully trimmed. Luxurious hair – black, lustrous and faintly suggesting a wave – thoroughly well groomed, leaving just the faintest doubt between natural carelessness or very

[Page 70]

(69)

deliberate, retouched, marcelled picturesqueness. Not a mane – but somehow suggest a mane – seeming too large for his light frame, making him vaguely top-heavy – more in impression than in fact. Thin, expressive hands and small feet, with a mincing, uncertain, unsteady, nervous walk.

Magnificent voice – a true achievement. Deep, low, well-modulated, clear, precise and expressive. Perhaps, a little offensive to some people, because of its too smug perfection – but to a very few people. Has made a thorough study of his voice-culture, but does not like to mention it – prefers to let people think it is natural. Shruggs deprecatingly when complimented on his voice, but never misses or forgets the compliments.

Went into “intellectualism” in a big way. Two reasons: first, a subconscious revenge for his obvious physical inferiority, a means to a power his body could never give him; second, and main – a cunning perception that only mental control over others is true control, that if he can rule them mentally he is indeed their total ruler. His vanity is not the passive one of Peter, who is really not concerned with other people as such, only as minions for his vanity; Flent Toohey is very much concerned with other people in the sense of an

[Page 71]

(70)

overwhelming desire to dominate them. His is the lust for power, but it is a “second-hand” power. It is motivated not by some deep conviction of his own to be imposed upon others, who would thus be secondary to him and his conviction, but by subconsciously adopting the convictions of others in order to rule them and thus acquire his own grandeur through the number of people he dominates, deriving his self-satisfaction from them, they actually being the prime factor and he a “second-hand” creature devoid of all personal significance but that given to him by others. In contrast to Peter, he does believe in ideals and convictions, does so very strongly and earnestly, but these ideals have to be his, or those he accepted as his. He is intolerant, impatient and sarcastic to all intellectual opposition. He believes in “principles”, realizing subconsciously that a strict adherence to a set of principles delivers men into his hands, particularly when he is the chief proponent of these principles. He is the loud[?est] defender of “intellect”, of “brain over brawn” or “mind over matter”. Such words as “culture”, “civilization”, “progress”, “the spiritual heritage of centuries”, “ethics”, “esthetics” and “philosophy” are his favorites, to the point where he has come to be convinced

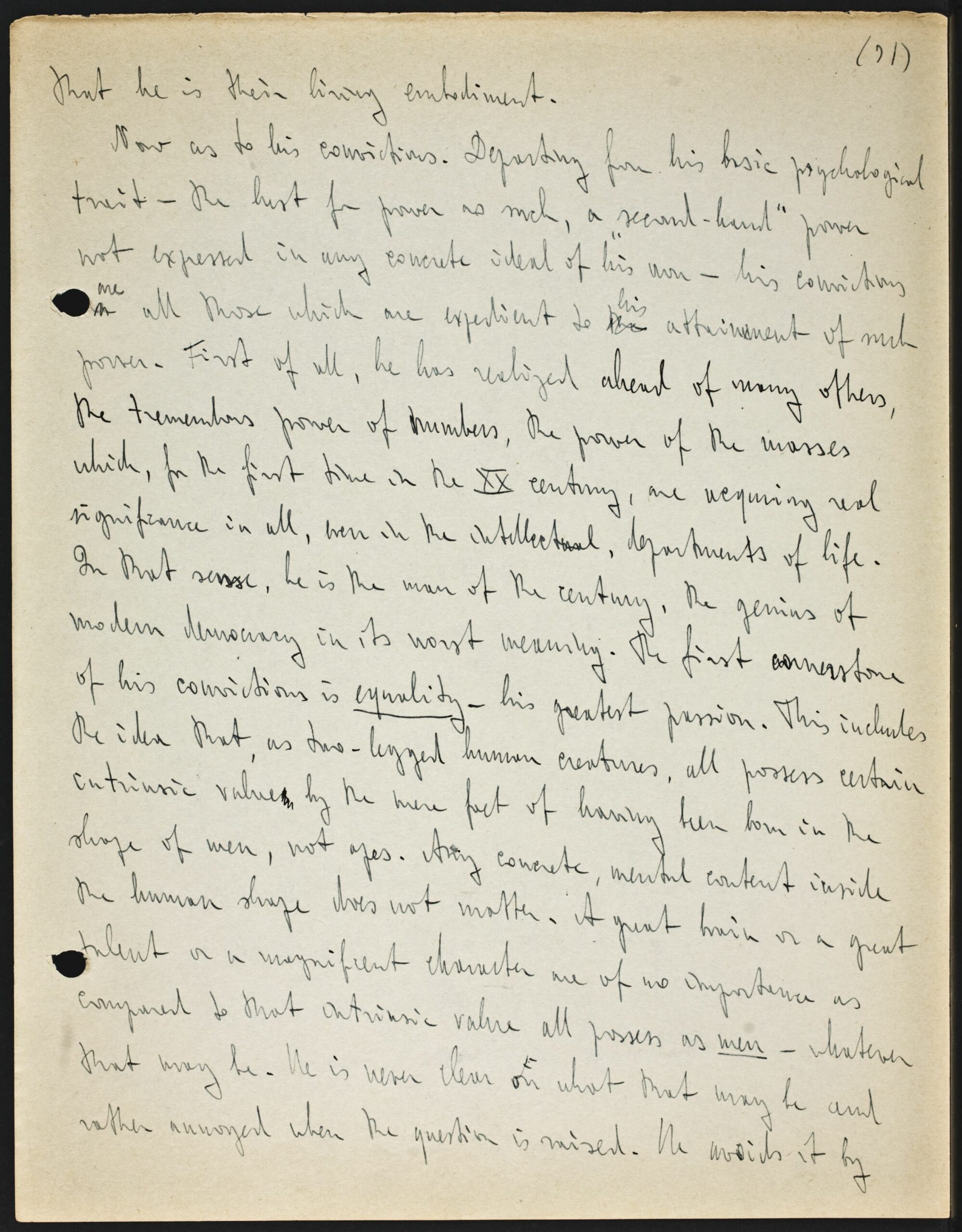

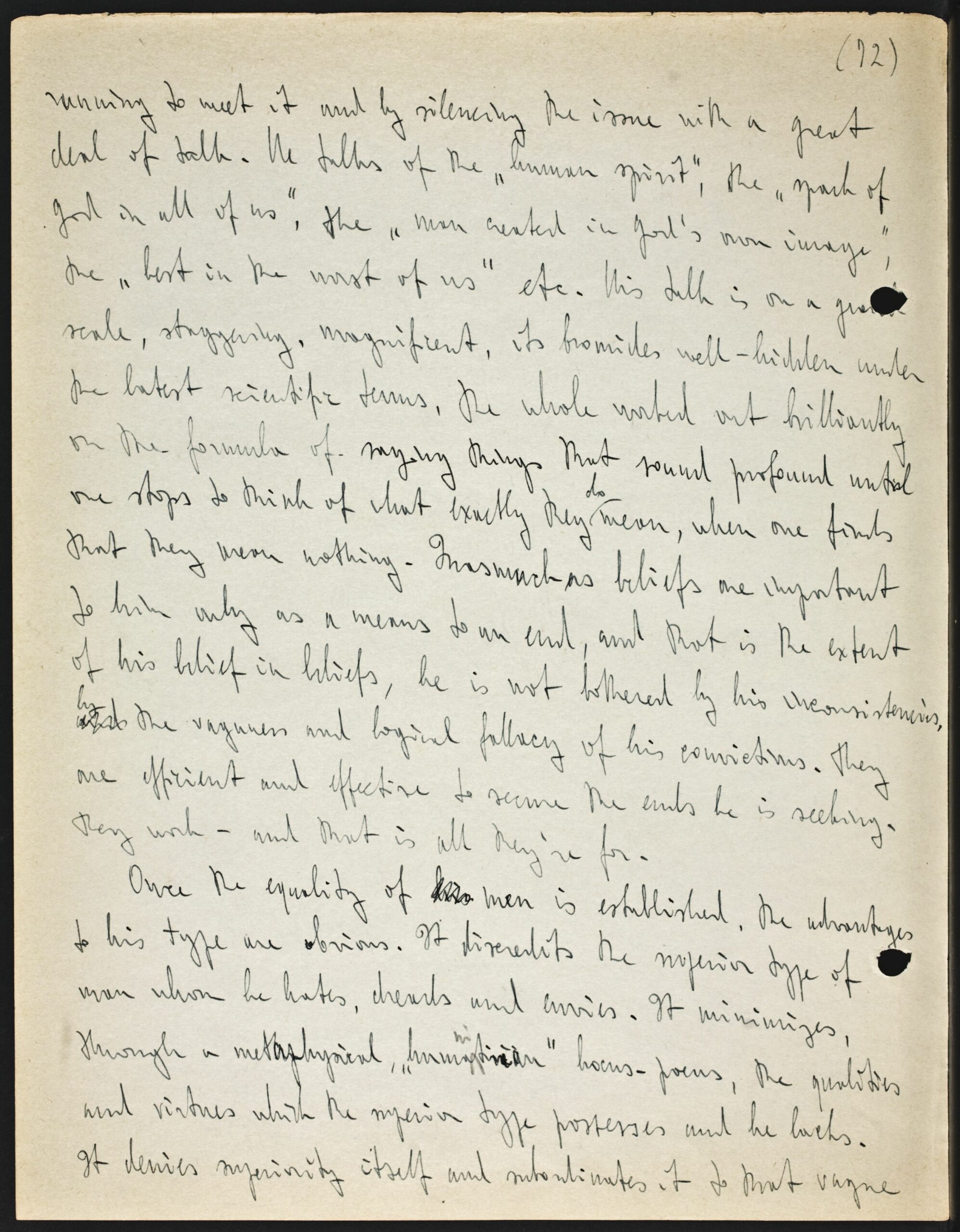

[Page 72]

(71)

that he is their living embodiment.

Now as to his convictions. Departing from his basic psychological trait – the lust for power as such, a “second-hand” power not expressed in any concrete ideal of his own – his convictions [illegible] are all those which are expedient to the his attainment of such power. First of all, he has realized ahead of many others, the tremendous power of numbers, the power of the masses which, for the first time in the XX century, are acquiring real significance in all, even in the intellectual, departments of life. In that sense, he is the man of the century, the genius of modern democracy in its worst meaning. The first cornerstone of his convictions is equality – his greatest passion. This includes the idea that, as two-legged human creatures, all possess certain intrinsic values by the mere fact of having been born in the shape of men, not apes. Any concrete, mental content inside the human shape does not matter. A great brain or a great talent or a magnificent character are of no importance as compared to that intrinsic value all possess as men – whatever that may be. He is never clear on what that may be and rather annoyed when the question is raised. He avoids it by

[Page 73]

(72)

running to meet it and by silencing the issue with a great deal of talk. He talks of the “human spirit”, the “spark of God in all of us”, the “man created in God’s own image”, the “best in the worst of us” etc. His talk is on a [?grand] scale, staggering, magnificent, its bromides well-hidden under the latest scientific terms, the whole worked out brilliantly on the formula of saying things that sound profound until one stops to think of what exactly they ⌄do⌄ mean, when one finds that they mean nothing. Inasmuch as beliefs are important to him only as a means to an end, and that is the extent of his belief in beliefs, he is not bothered by his inconsistencies, and by the vaguness and logical fallacy of his convictions. They are efficient and effective to secure the ends he is seeking. They work – and that is all they’re for.

Once the equality of his men is established, the advantages to his type are obvious. It discredits the superior type of man whom he hates, dreads and envies. It minimizes, through a metaphysical “humanitarian” hocus-pocus, the qualities and virtues which the superior type possesses and he lacks. It denies superiority itself and subordinates it to that vague

[Page 74]

(73)

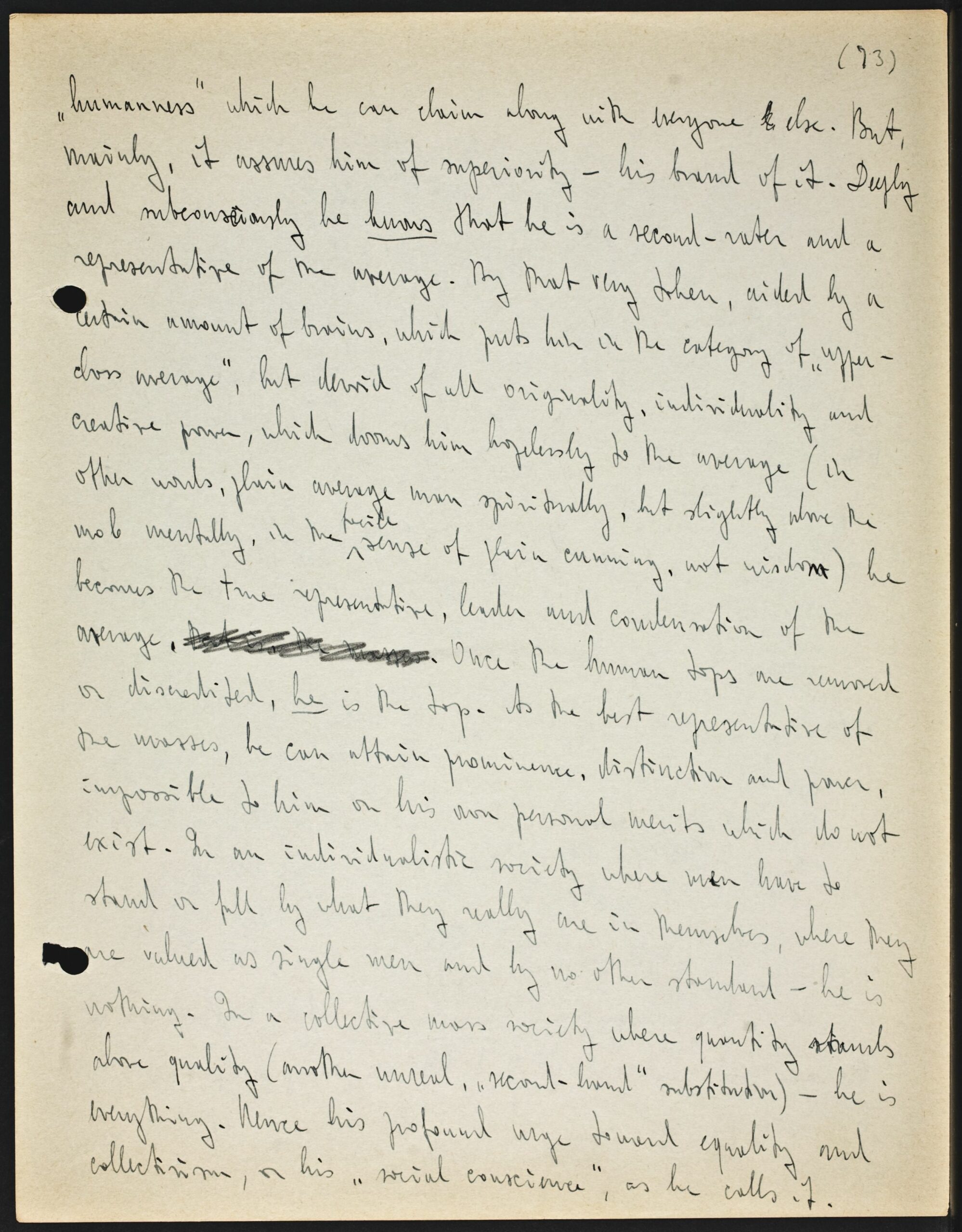

“humanness” which he can claim along with everyone l else. But, mainly, it assures him of superiority – his brand of it. Deeply and subconsciously he knows that he is a second-rater and a representative of the average. By that very token, aided by a certain amount of brains, which puts him in the category of “upper-class average”, but devoid of all originality, individuality and creative power, which dooms him hopelessly to the average (in other words, plain average man spiritually, but slightly above the mob mentally, in the facile sense of plain cunning, not wisdom) he becomes the true representative, leader and condensation of the average. that is, the masses. Once the human tops are removed or discredited, he is the top. As the best representative of the masses, he can attain prominence, distinction and power, impossible to him on his own personal merits which do not exist. In an individualistic society where men have to stand or fall by what they really are in themselves, where they are valued as single men and by no other standard – he is nothing. In a collective mass society where quantity stands above quality (another unreal, “second-hand” substitution) – he is everything. Hence his profound urge toward equality and collectivism, or his “social conscience”, as he calls it.

[Page 75]

(74)

This “social conscience” is an outstanding, dominant trait in him. He has a profound, instinctive interest in everything concerning others. He is the born, spiritual meddler, reformer and “social worker”. Societies, clubs, loges, organizations of any kind attract him irresistibly. His is not the cruder interest of Peter, who joins for what he him can get out of it. for himself. Flent Toohey joins to take an active part, for what he can do [illegible] to others. In everything he joins he soon becomes the leading voice and the influence. He is no rank and file member, ever; he is always on the committee or the board of directors. He is not after advancing his own career, he is after moulding the destinies lives of others, which is his career.(The monstrosity of “selfless” egotism) One will always find[?in] him on the stationary of “Slum Clearance” committees Leagues”, “Better Schools Mass Education Leagues”, “Modern Education Leagues”, “Recreation for the poor Leagues”, “Social Foundations Leagues” and prize-giving “Art Leagues”.

He is a “humanitarian” and a “radical”. Humanitarian, because his great love for and his eternal preocupation with humanity gives him the standing and prestige he does not

[Page 76]

(75)

possess as a man, fills the void of all individual creative impulse in him, a man who has nothing to offer in himself, only in, through and for others. (A “second-hand” type of man par excellence). (Only those who have nothing in themselves are too concerned with others.) Radical, because the theory of the triumphant, totalitarian mass is still a new one in the world, particularly in its spiritual implications and sources, which he realizes full-well, but never mentions explicitly. Up to the twentieth century and Soviet Russia, the world still went on on a semblance of recognition for individual achievement, recognition of leaders and exceptions as opposed to the mass; the trend of “liberalism” and the idea of “freedom” was freedom for “a man” and the recognition [illegible] fight for the individual rights of “a man”. When humanity achieved that freedom under after the industrial revolution, or came as near to that universal freedom and general equality before the law as it had ever come, one thing became apparent to the deluded idealists who, in fighting for the “rights of man” included all men, presumed all men to be equal, or at least potentially equal given equal opportunities. Whether under modern capitalism the best always won (and undoubtedly

[Page 77]

(76)

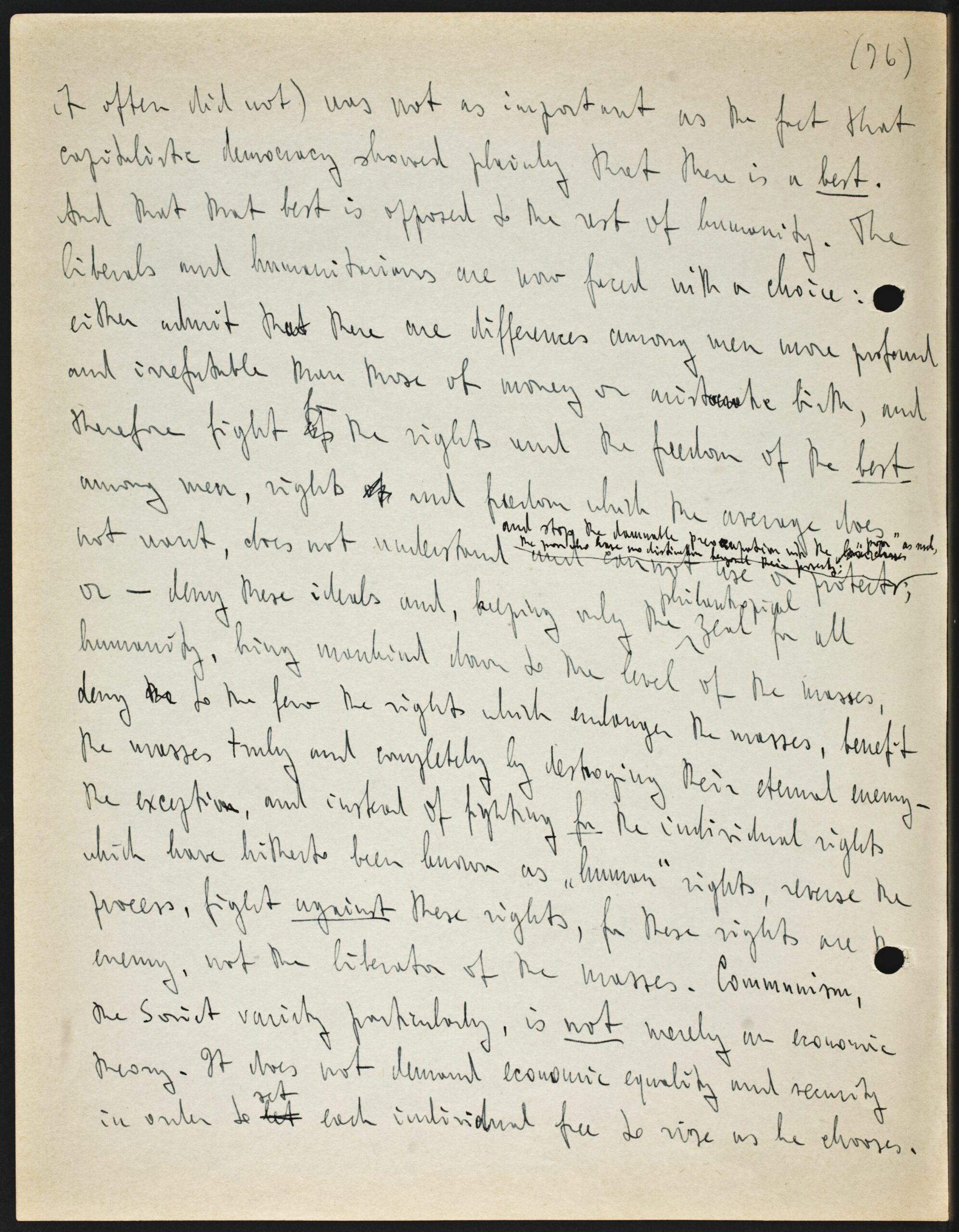

it often did not) was not as important as the fact that capitalistic democracy showed plainly that there is a best. And that that best is opposed to the rest of humanity. The liberals and humanitarians are now faced with a choice: either admit that there are differences among men more profound and irrefutable than those of money or aristocratic birth, and therefore fight of for the rights and the freedom of the best among men, rights of and freedom which the average does not want, does not understand and cannot use or protect ⌄and stop the damnable preoccupation with the lower classes“poor” as such, the poor who have no distinction beyond their poverty;; or – deny these ideals and, keeping only the philanthropical zeal for all humanity, bring mankind down to the level of the masses, deny the to the few the rights which endanger the masses, benefit the masses truly and completely by destroying their eternal enemy – the exception, and instead of fighting for the individual rights which have hitherto been known as “human” rights, reverse the process, fight against these rights, for these rights are [?the] enemy, not the liberation of the masses. Communism, the Soviet variety particularly, is not merely an economic theory. It does not demand economic equality and security in order to let set each individual free to rise as he chooses.

[Page 78]

(77)

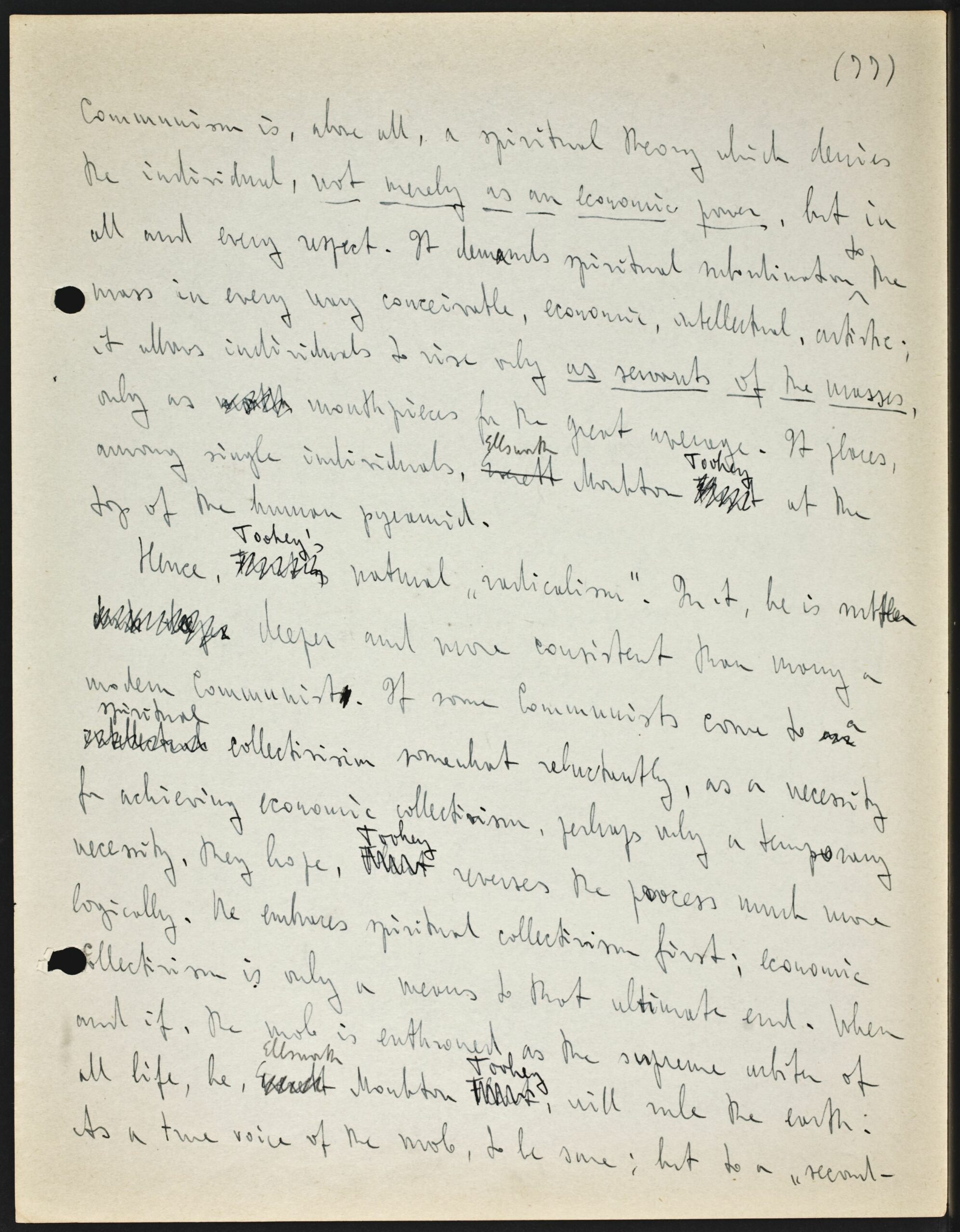

Communism is, above all, a spiritual theory which denies the individual, not merely as an economic power, but in all and every respect. It demands spiritual subordination to the mass in every way conceivable, economic, intellectual, artistic; it allows individuals to rise only as servants of the masses, only as [illegible] mouthpieces for the great average. It places, among single individuals, Everett Ellsworth Monkton Flent Toohey at the top of the human pyramid.

Hence, Flent’s Toohey’s natural “radicalism”. In it, he is subtler and deeper deeper and more consistent than many a modern Communists. If some Communists come to an a intellectual spiritual collectivism somewhat reluctantly, as a necessity for achieving economic collectivism, perhaps only a temporary necessity, they hope, Flent Toohey reverses the process much more logically. He embraces spiritual collectivism first; economic collectivism is only a means to that ultimate end. When and if, the mob is enthroned as the supreme arbiter of all life, he, Everett Ellsworth Monkton Flent Toohey, will rule the earth. As a true voice of the mob, to be sure; but to a “second-

[Page 79]

(78)

hand” man this does not matter. If What if he is only the servant spiritually – when there is nothing in his spirit which may wish to rule, no ideals, no convictions, no creative power strictly his personal own? Spiritual servility is not abhorrent to a man devoid of spirituality, in the only sense in which spirituality exists at all – in the powerful, self-contained, self-reverent ego. In actual, material life – devoid of all spiritual content, as a collective life must be, when the only source of spirit – the ego – is removed – he will be the ruler. He will have to no fear [?no] of competition from his spiritual superiors – since they will be destroyed, or if any are still born they will have no chance against him, lacking his power of mob appeal when the mob is supreme. And the only danger zone to his power – the spiritual or mental life of humanity – will be taken care of by an ever all-pervading saturation of propaganda of the ideals that made his rise possible, the ideals of mob supremacy, a smoke-screen to fill the void emptiness of the human spirit, a spirit castrated, denied and offered its own denial to satisfy its hunger.

[Page 80]

(79)

Such is Flent’s Toohey’s secret dream and Utopia in its ultimate conclusion – if it can ever be reached. He knows well all the possible approaches to it and all his convictions derive from that, have that dream as a motivation. Everything that procedes from the individual and the exception is bad; everything that procedes from the masses and the average is good. He takes a great interest in folklore, in anonymous legends and songs, as opposed to individual creations of artists. He proclaims the supremacy of “folk art” over any other art. He adopted the Marxist theory easily and naturally – for the chief reason that it discredits individual significance in history in favor of the economic significance of the masses; also – in subordinating the spiritual to the economic, in proclaiming the dependence of all spiritual culture upon the material one, it gives men like Flent Toohey the great weapon against their enemy – the spirit: just take the control of humanity’s economics – a thing easy, and concrete and accessible – and you control (or hope to) humanity’s spirit.

[Page 81]

(80)

In opposing the existing order of society, it is not the big capitalists and their money that Flent Toohey is opposesing: he opposes the faint conceptions of individualism still existing in that society, and the privileged few — as its material symbols. He says that he is fighting Rockefeller and Morgan; he is fighting Beethoven and Shakespeare. He says he is fighting for a comfortable home with a bathroom for every financially disinherited factory hand; he is fighting for a comfortable throne and a halo for every spiritually disinherited Flent Tooh Toohey. Hence his great preocupation with the poor and the lower classes. He is known as a great, unselfish crusader in unselfish causes; his crusade is thoroughly selfish in the perf perverted, unselfish selfishness of the “second-hand” ego.

It is not surprising, therefore, to find him with a reputation of “daring”, “progressiveness” and “originality”. He is all of that, in the sense that the total supremacy of the masses is a new idea in the world and he, as its apostle, may be considered daring or original. In that sense, he is the champion of everything “new”, particularly if it helps

[Page 82]

(81)

in the fight against the individualism of the old. He is a great champion of the Art Moderne. He is the defender and publicizer for Gertrude Stein in literature, the “surrealists” in painting, the cacophony of “new” music and the factory made standardized modern house in architecture. He knows, half-subconsciously, that all these [?fak] phony fakes are easy [illegible] for anyone and deny the great true originality, genius and rarity of great artists. In his chosen profession as an Art and Architecture Critic, he defends, above all, a standard. He is all for the old academic eclecticism, where it imposes rules, restraints and precedents on individual creation; he started as a rabid defender of eclecticism (“we cannot improve upon the masters of the past, accepted and recognized by whole nations and whole centuries of nations”) until he discovered a new standardization in the factory-made “moderne”, this last more in keeping with his social theories and his general reputation for radicalism. Before the spread of the “moderne”, he was opposed to modern architecture. And he has been opposed and is forever opposed to Howard Roark. Peter Wilson Keating is his true disciple and protege, and Peter with

[Page 83]

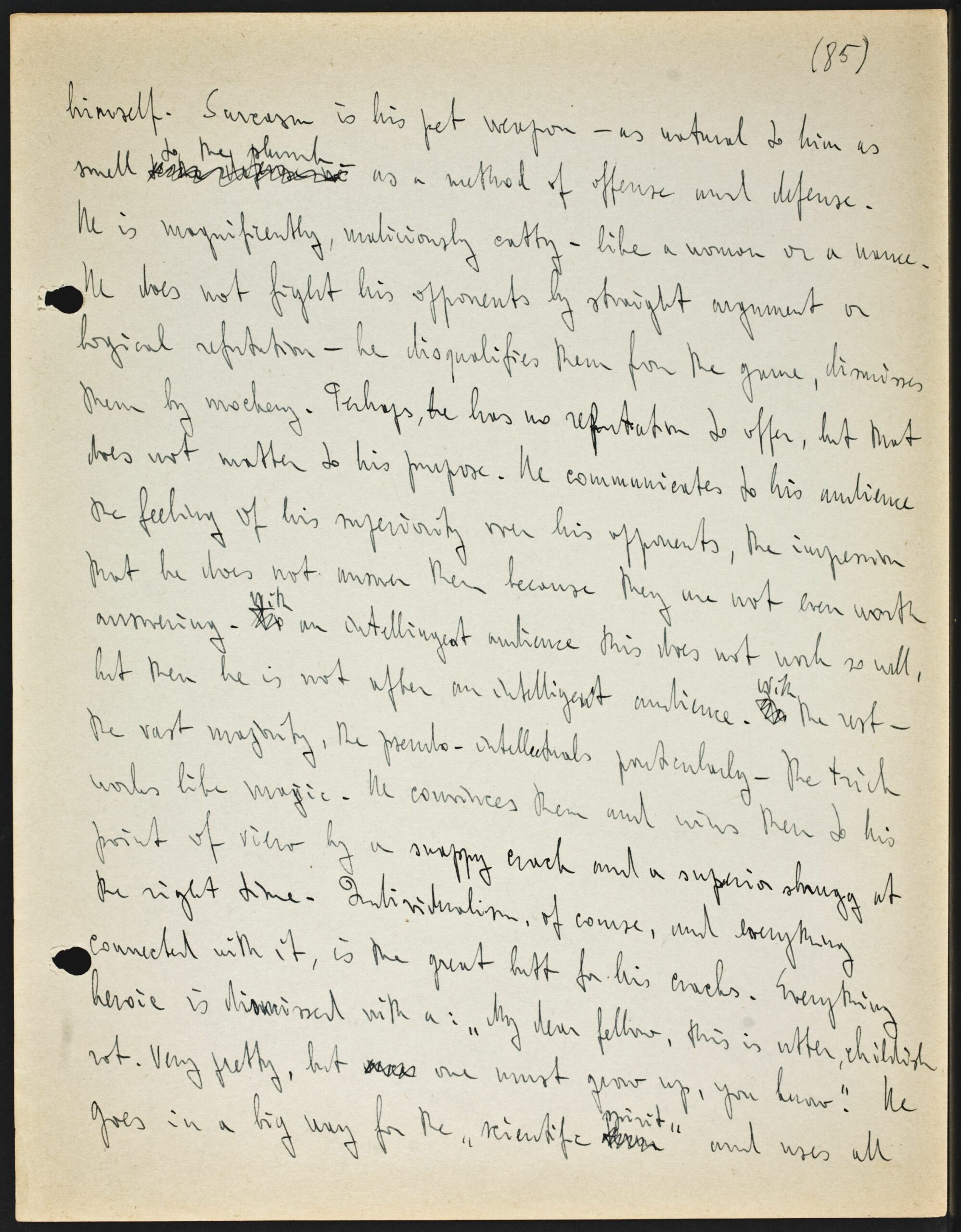

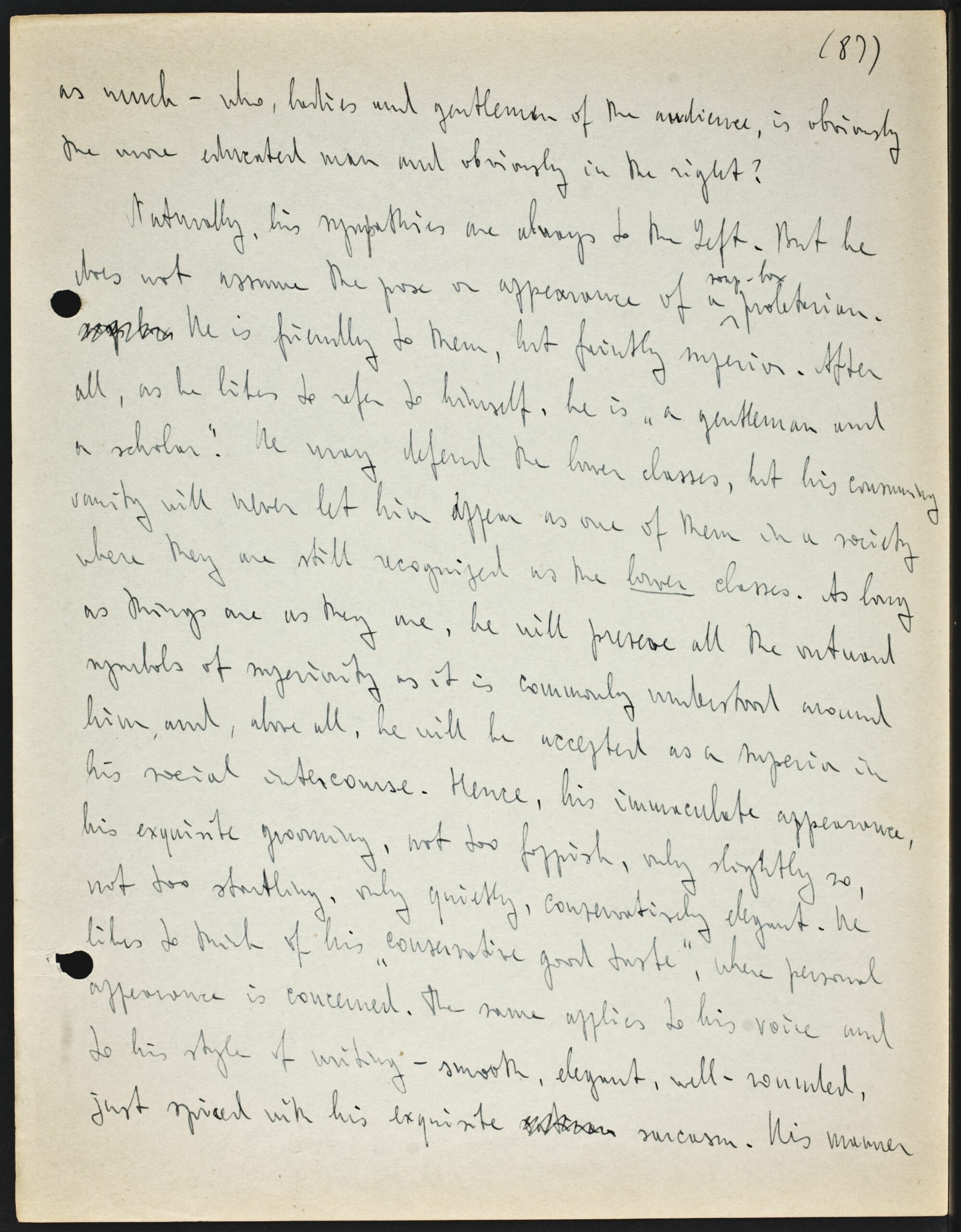

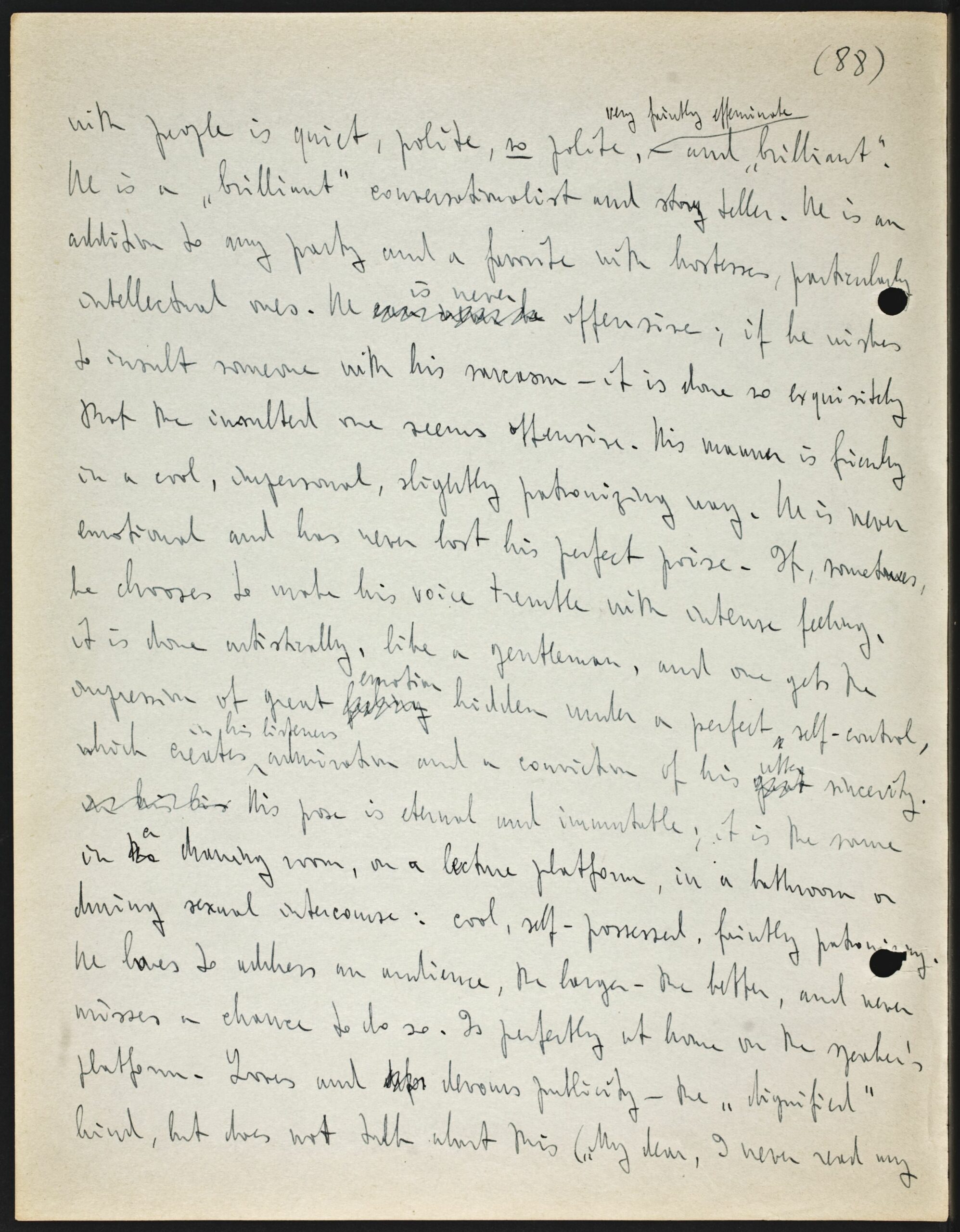

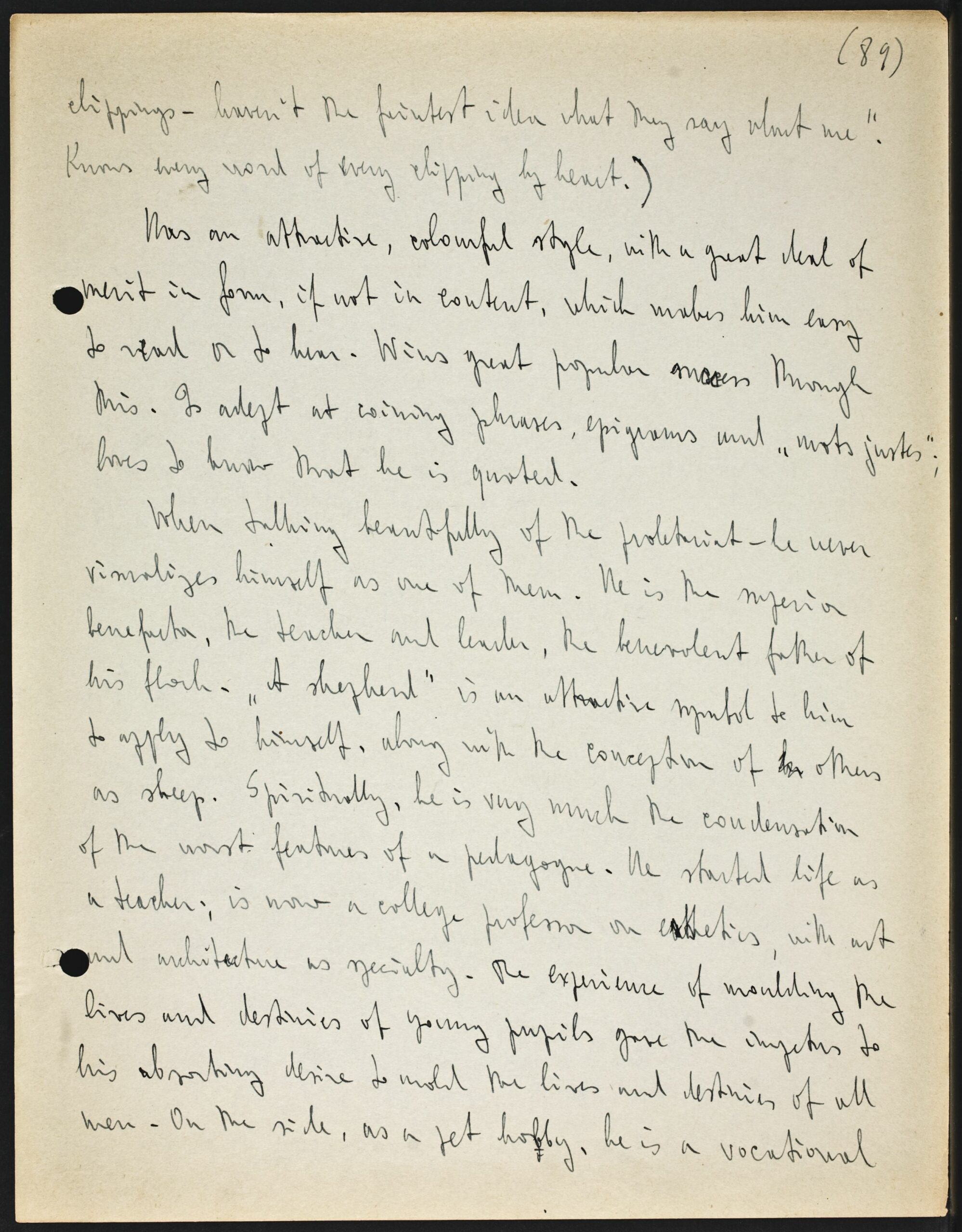

(82)