This letter was previously published only on the Ayn Rand Institute website.

[Page 1]

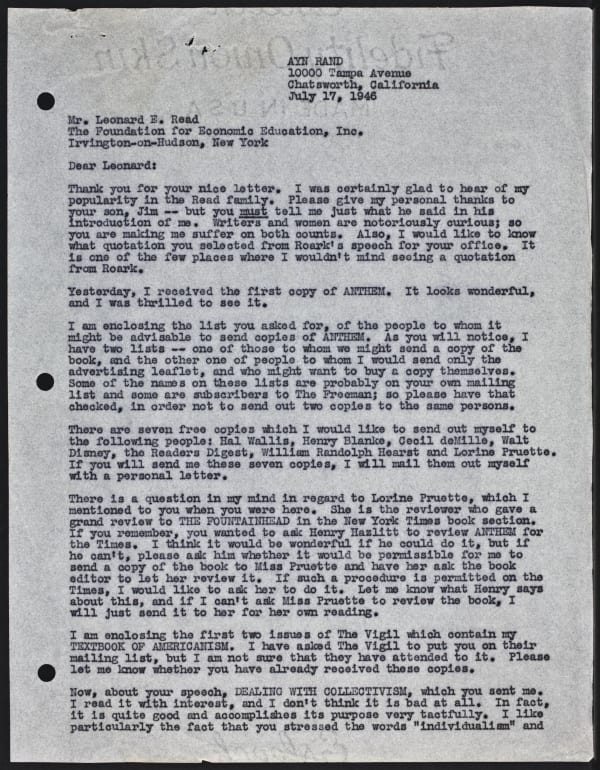

AYN RAND

10000 Tampa Avenue

Chatsworth, California

July 17, 1946

Mr. Leonard E. Read

The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc.

Irvington-on-Hudson, New York

Dear Leonard:

Thank you for your nice letter. I was certainly glad to hear of my popularity in the Read family. Please give my personal thanks to your son, Jim—but you must tell me just what he said in his introduction of me. Writers and women are notoriously curious; so you are making me suffer on both counts. Also, I would like to know what quotation you selected from Roark’s speech for your office. It is one of the few places where I wouldn’t mind seeing a quotation from Roark.[*]

Yesterday, I received the first copy of ANTHEM. It looks wonderful, and I was thrilled to see it.

I am enclosing the list you asked for, of the people to whom it might be advisable to send copies of ANTHEM. As you will notice, I have two lists—one of those to whom we might send a copy of the book, and the other one of people to whom I would send only the advertising leaflet, and who might want to buy a copy themselves. Some of the names on these lists are probably on your own mailing list and some are subscribers to The Freeman; so please have that checked, in order not to send out two copies to the same persons.

There are seven free copies which I would like to send out myself to the following people: Hal Wallis, Henry Blanke, Cecil deMille, Walt Disney, the Readers Digest, William Randolph Hearst and Lorine Pruette. If you will send me these seven copies, I will mail them out myself with a personal letter.

There is a question in my mind in regard to Lorine Pruette, which I mentioned to you when you were here. She is the reviewer who gave a grand review to THE FOUNTAINHEAD in the New York Times book section. If you remember, you wanted to ask Henry Hazlitt to review ANTHEM for the Times. I think it would be wonderful if he could do it, but if he can’t, please ask him whether it would be permissible for me to send a copy of the book to Miss Pruette and have her ask the book editor to let her review it. If such a procedure is permitted on the Times, I would like to ask her to do it. Let me know what Henry says about this, and if I can’t ask Miss Pruette to review the book, I will just send it to her for her own reading.

I am enclosing the first two issues of The Vigil which contain my TEXTBOOK OF AMERICANISM. I have asked The Vigil to put you on their mailing list, but I am not sure that they have attended to it. Please let me know whether you have already received these copies.

Now, about your speech, DEALING WITH COLLECTIVISM, which you sent me. I read it with interest, and I don’t think it is bad at all. In fact, it is quite good and accomplishes its purpose very tactfully. I like particularly the fact that you stressed the words “individualism” and

[Page 2]

Page 2 Mr. Leonard E. Read July 17, 1946

“collectivism” often enough and in the right places.

But I found one startling instance of giving our case away—which was surprising from you. This was the second paragraph on Page 5: “No true lover of liberty will admit that there is another side to the case. He may admit that he does not know how to accomplish everything by voluntary methods, but his thinking will be aimed at finding out. He knows that coercion is destructive except when it is used as police force to prevent interferences with personal liberty.”

The second sentence of this paragraph is a blatant denial of the first. It is an admission that there are things which we should accomplish, and which can be accomplished by coercion, but not by voluntary methods. What are these things? There is not a single issue, objective or purpose—and I mean none whatever—which is desirable but cannot be accomplished by voluntary methods. If anyone presents you with an objective which you cannot accomplish by voluntary methods, it merely means that it should not be accomplished at all, that the objective itself is evil and improper. I cannot imagine what you had in mind when you wrote that sentence. If, as an example, you meant some such objective as how to insure permanent prosperity to everybody, the answer is that it cannot be done and should not be attempted. Any objective which cannot be achieved voluntarily is a self-contradictory proposition, a request for the impossible.

That sentence in your speech is an admission that coercive methods work sometimes for good purposes and with good results. Surely, you do not believe that. If you do, it is a loophole through which a collectivist can destroy your whole case. Once you grant him that some proper objective can be accomplished by force, the rest of the argument becomes merely a squabble over which objectives you or he will consider proper. You have granted him his premise.

Please let me know what you had in mind. I am worried about this, because it is the first breach I have seen in your intellectual armor. If you are not clear on this point, I would like to discuss it further, as my first job in the position of your “loyal ghost”.

Also, the last sentence of your paragraph which I quoted is extremely inaccurate and bad in its implications. You describe the police power of the government as the power of coercion, and you place it in the same category as any other coercion exercised by a government. That is not correct. What the government does in regard to criminals is not coercion; it is not an action, but a reaction; the use of force to answer force. The use of force here is not initiated by the government but by the criminal. Therefore, it is not the same thing (and does not rest on the same principle) as the action of a government initiating the use of force for some “social” purpose of its own.

I cover this very point in the second installment of my TEXTBOOK OF AMERICANISM. I would suggest that you read very carefully my questions #7 and #8. I think the definitions I give there cover the case—and it is extremely important for our side not to mix the proper police powers of the government with its usurped powers of economic coercion. This is a crucial point which collectivists are using to the hilt; one of their most frequent arguments goes like this: “If the govern-

[Page 3]

Page 3 Mr. Leonard E. Read July 17, 1946

ment has the right to seize criminals, it also has the right to seize you.” We must not help them spread that kind of confusion.

There are two other points to which I object in your speech. On page 7, you mention as your aim: “Encouragement, including financial assistance, when necessary, to those scholars who are competent to produce such fundamental works as The Wealth of Nations, The Federalist Papers,” etc. This sentence sounds a bit naive. Such works as “The Wealth of Nations” or “The Federalist Papers” are achievements of genius, which is rare in any century, and they cannot be produced to order, just through financial assistance to scholars. I suggest that you say, instead, that you would like to provide financial assistance to scholars who can produce important works. That is the best any organization can hope to accomplish. Also, in the same paragraph, I would suggest that you do not quote Frederich Hayek. I believe you agreed with me as to the dangerous weaknesses of his book which are viciously destructive to our cause. Therefore, I would not help to publicize his book.

The last sentence of this paragraph, to the effect that the support of the intellectuals can be regained “only as their devotion and understanding are re-won” is quite a dubious sentence, because it seems to imply that this devotion is to be re-won by financial assistance, that is, in plain language, by a bribe. I am sure you did not want to give that impression.

On page 8, fourth paragraph from the bottom, I object to your sentence: “I have almost a mystic faith in what can be accomplished by pursuing a course of utter and complete honesty—”. This sentence implies the confession that the speaker does not believe in reason as the final and most powerful argument in support of the ideas he advocates. It implies that he considers mystic faith a more convincing basis for the truth of his ideas. I am sure that few of your listeners would realize this, but what I am concerned with here is your own attitude. Unless, you are convinced, firmly, unquestionably, totally, completely and absolutely, in your own mind and for your own purposes, that REASON, not mystic faith, is the proper basis for all human actions and convictions, you will not be able to achieve for yourself a clear and consistent philosophy of life. The issue of rationalism versus anti-rationalism is a much more profound one than that of individualism versus collectivism. In fact, the first issue is the root of the second. I could write volumes on this particular point—and intend to do it some day. For the moment, I hope that you will understand this and agree with me. If not, I will have to attempt to write you a longer treatise on this.

Please let me know whether I have convinced you in regard to these objections or not. I take my duties of “ghost” very seriously, and want to be sure that they are bearing fruit.

With best regards,

Sincerely,

Ayn Rand

*Read paraphrased what he remembered of his son’s reason for calling Rand “a great American”: the excellence of her advocacy of individualism and limited government. Read did not answer her question about the quote he selected from Roark’s speech.

Read answered Rand’s letter on July 19, 1946. He wrote that he agreed “wholly” with her criticisms re “points no. 7 and 8” (unidentified), and he admitted to some “careless writing,” “but that’s all.” Read also agreed with her comment about Hayek and said that he had already changed “mystic faith” to “proposed faith.” But he defended himself against her charge that he was “giving our case away.” He was, he wrote, referring to people who want to support liberty but don’t know how, not implying that coercion might be a legitimate option.